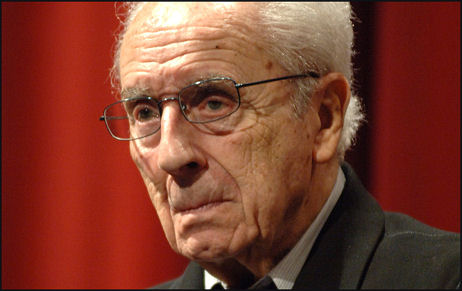

When I wrote my Ingmar Bergman obit yesterday morning, I called him “one of the four or five greatest film directors of the 20th Century.” And now Michelangelo Antonioni, the director of such drop-dead classics as L’Avventura, Blow-Up, L’Eclisse, La Notte and The Passenger who also belonged to this select quartet or quintet, is dead also. He and Bergman passed the same day — yesterday — according to most news services. An old man dying is never a tragedy, but two guys of this stature going within hours of each other…whoa.

The shallow view of Antonioni’s unquestioned genius period — L’Avventura to Blow Up — is that no one ever made better movies about the elite classes in the grip of exquisite nothingness. The longer, fuller view is that no one ever made better films about nothingness, period.

Very little happens in these and other almost-as-good Antonioni films (like Il Grido, Red Desert, Zabriskie Point)…but they’re all inescapably haunting. A little voice tells you each and every time you’re watching L’Eclisse or L’Avventura, “I can’t precisely explain to myself what this film’s about, but I know each and every frame is a bringer of some kind of fundamental, deep-down current…I can feel it in my soul.”

In his landmark films of the early to mid ’60s, Antonioni captured a certain spiritual ennui — feelings, intimations and observations of profound emptiness, alienation…a drifting-away from meaning and tradition. He was capturing the beginnings of the modernist flu that was infecting the moneyed classes back then, and has since enveloped everyone everywhere (even the guys in Entourage), and he did so with such immaculate composition and clarity that you can watch these films today and come away stunned at their immediacy, altogetherness and absolute lack of anything resembling fat. They do not date.

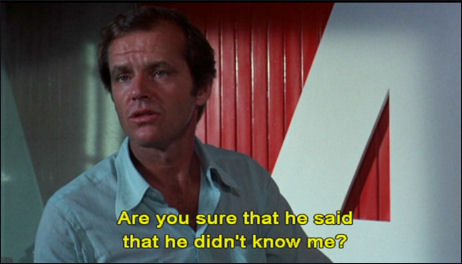

Pop in the Blow-Up DVD and chapter-flip to the moment when David Hemmings, portraying a hip London photographer who simultaneously knows everything and nothing, is snapping pictures of that couple in that park in suburban London — a younger woman and an older, well-dressed man, standing maybe 50 or 60 yards away. The thing that absolutely wows is the way a strong wind is rustling some nearby bushes and branches of trees, and how Antonioni somehow makes this primeval activity seem absolutely fraught with existential spookiness, and at the same time perfectly natural and innocuous.

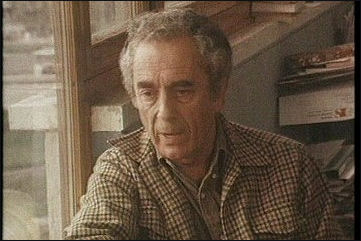

James Toback once told me a story about a coarse-sounding distributor (he may have been a bigwig with a company called Brut Films, which financed Fingers) who referred to this visionary artist as “Tonioni.” I’ve always laughed at this knowing there’s a measure of implied respect when even the worst people know about a certain film artist. It doesn’t matter if they get his or her name right; the fact that the brutes know him means everything.

The essence of Antonioni’s visual style is a frequent use of “lengthy tracking shots of human figures against a barren natural landscape or a scene of urban sterility,” a highbrow essayist once wrote. “He’s a visionary of emotional alienation, so morbidly convinced of the apartness of people that he sometimes ends his film by photographing figures in a landscape. There’s a feeling of social breakdown — a profound unease under the surface of things — permeating his work, but this is also accompanied (and this is the nub of his work) with a spellbinding visual grace.”

N.Y. Times critic Stephen Holden once described the Antonioni vibe as “brooding metaphysical mood music.”

In ’05 I was obliged to teach three UCLA extension film classes as part of my deal to host Sneak Previews. So for one of the classes I decided to go loopy and show Antonioni’s L’Eclisse (The Eclipse), an exquisitely composed black-and-white film about alienation and spiritual drainage among the aspiring classes in 1962 Rome.

I told the students this was a movie in which almost nothing happens, and that they may feel bored or frustrated by it initially. But I promised them they would never forget it, and that if they didn’t stop being film buffs they would eventually understand its greatness, although probably, in most of their cases, not until they hit their 30s or 40s.

I acknowledged that it’s essentially a movie about, in a manner of speaking, “nothing”…about a couple of attractive people (Monica Vitti, Alain Delon) eyeballing, toying and flirting with each other and having a bit of sex in the third act, but otherwise doing and saying relatively little, without anything resembling a story between them and certainly without any pronounced conflicts or resolutions.

But it has a certain seep-through effect. There’s a torrent of small things in L’ecclise that stay with you — dispirited looks, hints of eros and emotional voids, meditative moments, intimations of ennui and pointlessness. It doesn’t “say” anything but there are echoes all through it.

I showed them L’Eclisse because I know it’s one of the most sophisticated films of the 20th Century, and because the students would probably never see it on their own (it had recently come out on a spiffy new Criterion DVD) and because, as I said to them before showing it, no one in the commercial or semi-commercial realm is making films like this any more.

Critic and essayist David Thomson wrote the following a couple of years ago: “I can watch the world through Michelangelo Antonioni ‘s eyes forever. He is the greatest stylist of the modern era, and The Passenger may be my favorite film. It’s the one I think of offering whenever people ask that question. And they ask a lot.

“No, it’s not in my top ten, but sometimes I think The Passenger is the one I like the best, by which I fear I mean it’s the film I’d most like to be in, instead of just watching.

“Dream-projecting ourselves into films we really like is what many — most — of us do, I think, when we’re really taken by them. And when we’re watching films that we respect or admire but aren’t that into, that’s all we’re doing — watching from our side of the window.

“Every time I’ve re-watched any of Antonioni’s five or six greatest — La Notte, Blow-Up , L’eclisse, Il Grido, L’Avventura — I’ve felt this exact same urge to dissolve into a spectral cellluloid spirit, and disappear into the world of these films and wander around and maybe never come back. What would it be like to hang around in an Antonioni film after the movie is ‘over’? Mesmerizing, I would think.”