In early 2003 (or was it late ’02?) I pitched a big Matrix story to Rolling Stone‘s Peter Travers. With The Matrix Reloaded due to open on 5.15.03, I had gotten hold of a copy of the Wachowskis’ script and was looking to scoop the world with a few plot points (including the hair-raising freeway chase sequence) but without spoiling the whole thing. (Naturally.) I’d also picked up some odd domestic details about The Wachowskis, who were then called Larry and Andy and known for being extra-reclusive.

Travers was interested in running a scoop of this kind. We sat down and talked it over at a Manhattan eatery. I didn’t know for a fact that Travers had briefed Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner, but it would have been odd if he hadn’t.

The Reloaded script had been passed to me by former Silver Pictures executive Dan Cracchiolo, who had worked for the company’s founder, Joel Silver, between the mid ’90s and early aughts. Dan had struck out on his own a year or so earlier, although I suspected that things may have soured between Silver and himself over possible drug issues — Dan’s, I mean.

I had been especially chummy with Silver between mid ’92 and early ’94, but then relations chilled. (The reasons are too complex to recite here.) The occasionally tempestuous Silver was the real-life model for Saul Rubinek‘s “Lee Donowitz” character in True Romance. (It’s also been said he was at least a partial model for Tom Cruise‘s “Les Grossman” in Tropic Thunder.)

In any event I met with Travers to discuss the shape and tone of the Reloaded article — a few Wachowski morsels, a few plot leaks but not too many, etc. I tapped it out and sent it along. The article definitely worked on its own terms but of course it had to be fact-checked and whatnot. Which meant calling Silver, of course. It was my understanding that Silver hit the roof and called Wenner to yell and scream.

The next thing I knew the piece had been killed. When I called and wrote Travers to ask what happened he wouldn’t respond…silencio. I presumed it had been killed by Wenner. I can’t recall if I was paid a kill fee. I only know that the Rolling Stone vibes were pretty good before I turned the piece in, but after it was killed I was Nowhere Man.

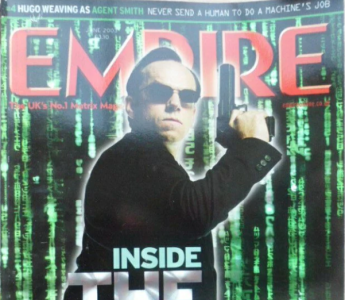

So I sold the article to Empire magazine, and it wound up running right around the time of the May opening of The Matrix Reloaded. Nobody liked the film that much, and everyone hated The Matrix Revolutions.

Dan died in a motorcycle accident the following year.

“Weight of Lavish Living,” posted on 6.26.19:

Yesterday’s news about legendary producer Joel Silver, 66, leaving Silver Pictures didn’t seem to add up.

A onetime protege and producing partner of Larry Gordon, Silver launched the company in ’80, built it into a strong and successful action-flick shop, co-pioneered the whammy-chart approach to action films, earned hundreds of millions for Warner Bros. (the Lethal Weapon, Die Hard and Matrix franchises, Predator, The Last Boy Scout, Assassins, Swordfish, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, V for Vendetta, The Nice Guys).

Things began to wind down when Silver’s longstanding partnership with Warner Bros. ended, and then a subsequent Universal deal didn’t pan out. Silver then partnered with Canadian private equity financier Daryl Katz.

But how does a guy who blazed his own high-powered trail and created his own self-named fiefdom…how and why does the commandant of Silver Pictures wind up leaving Silver Pictures?

According to The Hollywood Reporter‘s Borys Kit, the big-spending Silver (owner and renovator of Auldbrass, a South Carolina plantation estate built by Frank Lloyd Wright, as well as a former owner of the Wright-designed Storer House as well as a Wright-designed 1941 Lincoln Continental), more or less torpedoed himself by blowing too much dough while failing to produce enough hit films.

“It is unclear whether Silver was fired or left on his own accord,” Kit reports.

“Silver rose to prominence in the era of the non-writing movie producer, a time when he and peers like Jerry Bruckheimer could command $2.5 million plus a cut of first-dollar gross on a studio film. Warner Bros. was a home to him, advancing him money when he needed it and assigning him big-budget features to develop and produce. As he rose in prominence, Silver purchased homes in Brentwood, Malibu and South Carolina, as well as an art collection he once valued at $17 million, courtside Lakers seats and the architecturally significant Venice Post Office property near the ocean in Venice Beach.”

I was chummy with Silver for a couple of years in the early ’90s — late ’92 through ’94. Then relations chilled. Too complex to recite here. Silver has a legendary temper. He was the real-life model for Saul Rubinek‘s Lee Donowitz character in True Romance. It’s also been said that Silver was a partial model for Tom Cruise‘s Les Grossman in Tropic Thunder.

Posted on 4.26.07: “The late Dan Cracchiolo, the hot shot get-around who worked as Joel Silver‘s top guy in the mid to late ’90s and a little beyond, once told me about a conversation he and Silver had about the size of the craniums of big movie stars. He said that Silver told him, ‘Dan, all big stars have really big heads.’ Physically, he meant.”

Form “Heal Thyself,” posted on 11.17.16: “You may not find this fact in film-history books, but 1987 was a seminal year for the tarnished moral and ethical authority of the proverbial investigator and law enforcer (i.e., the loosely-allied private dick and big-city cop) in Hollywood films. For this was the year in which they both succumbed to the forces of darkness and crazy-hood.

“Shane Black, Richard Donner and Joel Silver‘s Lethal Weapon introduced the then-radical idea of a cop who was screwier and possibly more dangerous than the criminals he was chasing. ’87 was also the year when Alan Parker‘s Angel Heart told the tale of a wise-guy shamus who turned out to be the very same grisly murderer he’d been looking to find all through the film.

“Before these two movies cops and private eyes were thought to be more or less safe — corrupted and flawed to varying degrees (like Treat Williams‘ narcotics cop in Prince of the City) but still vaguely decent, semi-trustworthy, on ‘our side’, exuding a recognizable sense of morality. These two films changed all that.”

The Hollywood Reporter‘s Kim Masters wrote a tough-focus profile of Silver in 2015, titled “The Epic Saga of Joel Silver: Money Struggles, Feuds and Another Second Chance.”

Here’s the only snap I could find of Cracchiolo: