Speaking as a devoted admirer of Bennett Miller‘s Capote and Moneyball, it gives me no pleasure to admit that I feel a tad less enthusiastic about Foxcatcher, which screened this morning at the Cannes Film Festival. There’s no doubt that Foxcatcher is very strong and precise and clean, especially as crime dramas tend to go. And I respect the fact that it contains undercurrents that stay with you, and I certainly respect and admire what Miller has done here with his deft and subtle hand. But the obviously intelligent Foxcatcher is a relentlessly bleak trip that, accomplished as it is, isn’t especially likable or enjoyable. Okay, I “liked” it or…you know, I didn’t “dislike” it because it’s so well-made and refined, etc. But it’s basically a grim study of a dark tale about victims and affluent malevolence and corrupting wealth, and about fate surrounding the characters like tentacles and sucking them down the drain.

No savvy players, no smart detectives, no wise guys, no sex, no heroes, no winners, no zingy dialogue…its a down concerto from start to finish.

Please don’t get me wrong — this is a carefully honed, highly disciplined smart-guy melodrama. I admire the shit out of it, and I will never speak ill of it. But it’s still a downbeat thing about the pursuit of Olympic wrestling glory by a couple of weird obsessives — the late multimillionaire and convicted murderer John DuPont (Steve Carell), and real-life, grim-faced 1984 Olympic wrestling champion Mark Schultz (Channing Tatum) — and Mark’s kind-hearted, steady, positive-minded older brother Dave Schultz (Mark Ruffalo), a married ex-wrestler and coach who got caught in the middle when DuPont shot him to death in 1996. The film is about creepy currents and unstated agendas that lead to perplexing tragedy, and it all happens in gloomy rural Pennsylvania — an atmosphere that has always seemed to have a narcotic-like effect upon my system or mood or whatever. I only know that whenever I’m in rural Pennsylvania I want to escape.

You could make a case for Foxcatcher being a metaphor for malevolent tendencies among the patriotic super-wealthy establishment and other perverse aspects of our cultural submission or subugation. It’s all there if you want roll around in it.

You can’t help but salute Steve Carell‘s performance as DuPont, and the sly way that he suggests all kinds of deep down fucked-up stuff — a mixture of pride, anger, maternal resentment, control-freak mania, homosexual repression and madness. And the physical transformation (including the use of a putty hook nose) is impressive. Not to mention the first-rate costarring performances by Mark Ruffalo and Channing Tatum as Dave and Mark, respectively, as well as a noteworthy if brief performance by Vanessa Redgrave as DuPont’s mother. Sienna Miller is barely on-screen (she has maybe five or six lines, if that) as Dave’s wife.

The script by Dan Futterman (Capote) and E. Max Frye is basically about a kind of triangle, not romantic but emotional as all get out. Tatum’s Mark is the object of obsession or affection. Carell’s DuPont is the emotional aggressor who aspires to be not just Mark’s wrestling benefactor but his mentor and coach and father. And Ruffalo’s Craig is the third element, a guy whom Dupont has hired to coach at the Foxcatcher wrestling academy but whom he also sees as emotional competition for Mark.

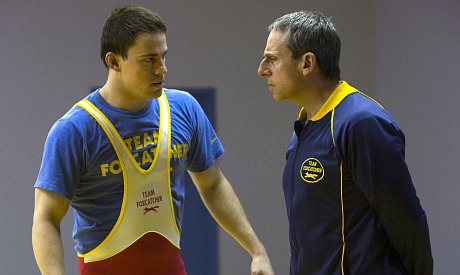

Channing Tatum, Steve Carell in Bennett Miller’s Foxcatcher.

I know that the film suggests over and over that DuPont is an obsessive who wants to control everyone around him, but it never suggests that he’s literally unglued in a wackadoo sense.

And yet the following is from a People magazine story about the Dupont’s February 1996 murder of Craig, to wit: “Lately [DuPont] had started telling people he was the Dalai Lama. If anyone refused to address him as such, he simply refused to talk to them. That was bizarre, but then John E. DuPont, 57, a multimillionaire scion of the fabled industrial family, had always been odd. For fun he drove an armored personnel carrier around his 800-acre estate, Foxcatcher. He complained about bugs under his skin and about ghosts in the walls of the house. By and large, friends and family shook their heads, fretted about his ravings—and waited for the inevitable breakdown.

“‘John is mentally ill and has been mentally ill for some time,’ says sister-in-law Martha du Pont, who is married to John’s older brother Henry. ‘But this year he really went over the edge.”

There was also a two-day standoff following the murder with DuPoint holed up inside his mansion and the place surrounded by the cops. The movie ignores this.

Also from People: “Du Pont’s romantic life was a matter of speculation among athletes and friends. A bachelor until he was 44, in 1983 he married 29-year-old Gale Wenk, an occupational therapist who had cared for him after he injured a hand in an auto accident. Ten months later he filed for divorce. Some athletes and coaches suspected that he had become interested in wrestling for more than sporting reasons. As Jerry Stanley, a former assistant coach at the University of Oklahoma, told one reporter, ‘I think he just liked to be around these Greek Adonis-built types.’ This is indicated in the film but Miller doesn’t stir it up or poke at it.

I don’t know what I’m saying but maybe it’s this: the story of John DuPont and the Schultz brothers may be a little crazier and more crudely distracting — something that fits right into the People template — than what Miller, a man of fine impeccable taste, may have been willing to exploit. I’m not saying I don’t relish Miller’s perceptions or his exquisite eye and the restraint he always defaults to in his films. I’m saying that Foxcatcher feels very pruned and shrouded and meticulously assembled, and that maybe what the movie needed was a little cheap vulgarity just to round things out.

This has not been a pan. It’s basically been a statement of sincere respect for Miller’s craft and commitment to a certain aesthetic combined with an honest gut reaction. I hope I won’t be misinterpreted.