A combination of (a) zonking out for four hours late this afternoon (2 pm to 6 pm) and (b) the nostril wifi agony that was injected into my life by the Grand Wyndham Berlin Hotel has delayed my review of Wes Anderson‘s The Grand Budapest Hotel, which I’ve seen twice now — in Los Angeles last Monday afternoon and again today at Berlin’s CineMAX plex. Rest assured that while Budapest is a full-out “Wes Anderson film” (archly stylized, deadpan humor, anally designed) it also delights with flourishy performances and a pizazzy, loquacious script that feels like Ernst Lubitsch back from the dead, and particularly with unexpected feeling — robust affection for its characters mixed with a melancholy lament for an early-to-mid 20th Century realm that no longer exists.

Budapest (Fox Searchlight, 3.7) is a dryly fashioned experience but a sublime one. It feels like a valentine to old-world European atmosphere and ways and cultural climes that began to breath their last about…what, a half-century ago if not earlier? This is easily Wes’s deepest, sharpest and most layered film since Rushmore, which, believe it or not, came out 15 years ago.

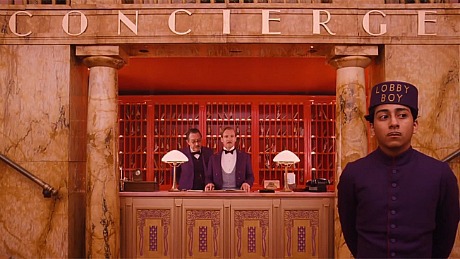

Set mostly in 1932 within an imaginary but highly mythical and mountainous Eastern European country called Zubrowka (a blend of old Czechoslovakia, Romania, Hungary and Transylvania), Budapest is a kind of old-world adventure-comedy farce, told as a flashback-within-a-flashback and, typical for Anderson, sly and mannered and tableau-ish. It’s basically propelled by a jaunty, faintly perverse tale of a wrongfully accused hero (Ralph Fiennes‘ rakish Gustave H., the head concierge of the tres elegant Grand Budapest Hotel) as he tries to clear his name and keep a valuable painting called “Boy With Apple” (the MacGuffin of the piece) from falling into villainous hands, and by the end of the day set things right, which is to say restore and maintain the good things in life.

But he can’t. In a sense his hands are tied because the world — Gustave’s world, which is to say Anderson’s — is coming undone even in ’32, and is about to fall prey to fascism (Anderson has substituted the Nazi swatztika with a ZZ) and thuggery and war and swirling storm clouds that would stop Cecil B. DeMille in his tracks.

Budapest is about the erosion of civilization, of gentlemanly standards, of civility and taste and discretion and refinement and the very best behavior among men and women of impeccable character and honor. And about the slaughterhouse atmosphere that would eventually ignore and obscure if not suffocate it.

Budapest is “studied,” of course, and largely composed of static, exquisitely framed capturings of self-obsessed eccentrics riffing and cavorting within a series of exotic realms — standard Anderson stuff. But this time the focus is a disappeared way of life, and for once Wes’s formalism has a stylistic point — here it feels like a metaphor for order, for the succinct style and rhyme and flavor of the way things used to be. That’s the sad or bittersweet part because that world is, for the most part, all but erased if not forgotten.

The good part is that The Grand Budapest Hotel is really quite good — easily the first upscale-film-culture standout of 2014 if you don’t count the seven or eight Sundance films that everyone liked.

Post-Rushmore it took Wes forever to get past his design-for-design’s-sake movies, and now he’s finally done it. Or at least he’s stretched himself and deepened his shadings and made a movie that has a palpable undercurrent and a gentle tone of sadness that stays with you. It’s a marvel to sink into it a second time. I enjoyed Budapest a bit more today than I did last Monday because its so much damn fun to just watch and savor from a purely visual standpoint. Not to mention the performances, first and foremost by Fiennes (his best since Schindler’s List?) but also costars F. Murray Abraham, Mathieu Amalric, Adrien Brody, Willem Dafoe, Jeff Goldblum, Harvey Keitel, Jude Law, Bill Murray, Edward Norton, Saoirse Ronan, Jason Schwartzman, Lea Seydoux, Tilda Swinton, Tom Wilkinson and Owen Wilson.

On top of which a good 85% to 90% of The Grand Budapest Hotel is presented in a boxy, Shane-like aspect ratio of 1.37 to 1, mostly in vibrant color but also, at the very end, in black and white. (Along with brief deployings of 1.85:1 and 2.39:1.) Are you kidding me? This is the kind of visual experience that I dream about and live for. I was often choked up with delight at the luminous and exacting compositions, not to mention the sheer jungle-bestial pleasure of knowing that the 1.85 fascists will have no choice but to zip it and accept it. Boxy is beautiful, gentlemen, and this is exhibit A in the year of our Lord 2014.

Anderson has crossed an artistic Rubicon with The Grand Budapest Hotel, and from here on there can be no more no more Life Aquatic exercises, no more referencing Dalmatian mice for style’s sake alone. He’s finally broken out of his effete parlor passions phase. All artistic breakthroughs in any realm require cheers and champagne, and this is no exception.

Six or seven years ago it was agreed by movie cognescenti that Anderson had allowed his films to be consumed by a deadpan mannerist attitude along with a certain style-and-design mania, which had devolved, in the view of Esquire‘s David Walters, from a signature into “schtick.” By making movies about “world-weary fellows” with money “who hurl non-sequiturs and charm with endearing peccadilloes and aberrant behavior” in a world-apart realm, Anderson, he wrote, “has painted himself into a corner.”

Now Wes has painted himself out of it. Or pulled himself out of it with a rope ladder. Or written himself out with relish and flair.

There’s a classic line about graceful aging or adjusting one’s lecherous appetites…one of the two. Fiennes’ M. Gustave is telling Tony Revolori‘s Zero Moustafa, a Grand Budapest hotel bellboy who becomes his staunch ally and fellow adventurer, that he Biblically “knew” Swinton’s recently deceased Madame D., an elderly millionaire who has willed him the “Boy With Apple” painting. Noting that she was “great in the sack,” Fiennes explains that “in your youth it’s all fine filet but as you get older you have to settle for the cheaper cuts.” Or words to that effect.

That’s generally true if you’re not married, but for the middle six months of 2013 I was utterly blessed by a relationship with an exquisite, marbled, grass-fed filet mignon, to go with the metaphor. (Which I don’t feel all that good about now that I’m thinking about it. It was as much a matter of vulnerability and giving and spiritual bonding as anything else.) God smiled, and I will never forget His generosity. Despite the woundings at the end I caught an amazing break.