It took them several years, but Warner Home Video is finally about to release a big swanky DVD of the 1962 Marlon Brando version of Mutiny on the Bounty. The film has been re-mastered from the original 65mm elements and will be presented in the original 2.76 to 1 Ultra-Panavision aspect ratio. This version hasn’t been seen by anyone since Bounty‘s big-city, reserved-seat showings some 44 years ago.

It’ll be part of a spiffy new Marlon Brando Collection box set hitting stores on 11.7.06. The set will also include a purist remastering of John Huston‘s Reflections in a Golden Eye (’67) that will recreate the golden pinkish hues that this disturbing film was presented with during its initial run. It’ll also include a remastered version of Joseph L. Mankiewicz‘s Julius Caesar (’53), which I wrote an item about just a few days ago.

(l. to r.) Trevor Howard, Marlon Brando, Richard Harris and Percy Herbert in Lewis Milestone’s Mutiny on the Bounty

The lesser titles in the set are Teahouse of the August Moon (’56), which features Brando’s strange performance as a cheerful Taiwanese translator named Sakini, and John Avildsen’s The Formula (’80), in which a fat, white-haired Brando plays a no-good oil company mogul.

Say what you will about the ’62 Bounty‘s problems — historical inaccuracies and inventions, Brando’s affected performance as Fletcher Christian, the floundering final act. The fact remains that this viscerally enjoyable, critically-dissed costumer is one of the the most handsome, lavishly-produced and beautifully scored films made during Hollywood’s fabled 70mm era, which lasted from the mid ’50s to the late ’60s.

Roger Donaldson‘s The Bounty (’84) is probably a better Bounty flick (certainly in terms of presenting the historical facts), but the ’62 version has more big-buck, oom-pah swagger. The sets seem flusher and more carefully varnished and arranged, Robert Surtees‘ widescreen photography is more vivid and precisely lit and generally more eye-filling than Arthur Ibbetson‘s for The Bounty, and Bronislau Kaper‘s orchestral score is more deep-down stirring than the quieter ’84 score by Vangelis.

The Brando Bounty is a dated film in some ways (okay, a lot of ways), but it has a flamboyant “look at all the money we’re spending” quality that’s half-overbaked and half-absorbing. It’s pushing a kind of toney, big-studio vulgarity that insists upon your attention.

There’s a way to half-excuse Bounty for doing this. It was made, after all, at a time when self-important bigness was regarded as a kind of aesthetic attribute unto itself, with large casts, extended running times, dynamic musical scores (overtures, entr’actes, exit music) and intermissions all par for the course. And there’s no denying that a lot of skilled craftsmanship and precision went into this manifestation.

The act that ignites the mutiny scene as Brando’s Fletcher Christian tries to give fresh H20 to a thirsty seaman, and Howard’s Cpt. Bligh expresses his opposition.

Bounty definitely has first-rate dialogue and editing, and three or four scenes that absolutely get the pulse going (leaving Portsmouth, rounding Cape Horn, the mutiny, the burning ship). And I happen to like and respect Brando’s performance — it gets darker and sadder as the film goes along — and you can’t say Trevor Howard‘s Captain Bligh doesn’t crack like a bullwhip. (I read a review that said his emoting was made from “wire and scrap iron”, and that Brando’s came from “tinsel and cold cream”.) And Richard Harris and Hugh Griffith are fairly right-on. And everybody likes the topless Tahitian girls.

You could argue that this Bounty is only nominally about what happened in 1789 aboard a British cargo ship in the South Seas. And you could also say that its prime fascination comes from a portrait of colliding egos and mentalities — a couple of big-dick producers (Aaron Rosenberg was one), several screenwriters, at least two directors (Lewis Milestone, Carol Reed) and one full-of-himself movie star (Brando) — trying to serve the Bounty tale in ’60, ’61 and ’62, and throwing all kinds of money and time and conflicting ideas at it, and half-failing and half-succeeding.

Seen in this context, I think it’s a trip.

I frankly expected WHV to go with a 2.55 to 1 aspect ratio. 2.76 to 1 is fairly radical. It means you’ll be looking at thicker-than-normal black bars above and below the image. (If you want an example, check out the most recent DVD of Ben-Hur.) This means you’d better watch it on a fairly large screen.

Here’s are four samples from Kaper’s score — the overture, an unused overture, a romantic idyll piece on Tahiti and a replay of the main theme.

The Bounty DVD is a two-disc affair, but apparently it won’t offer a “making of” documentary. (The doc on the second disc is called “After the Cameras Stopped Rolling: The Journey of the Bounty”, which obviously isn’t about what happened before and during the rolling of the cameras.) That’s a shame because Bounty‘s production history is one of the most tortured in Hollywood history, marked as it was by constant tempest (Reed was let go, Milestone quit), cost overruns and Brando’s brash big-star behavior. It was almost as costly and disastrous as the shooting of Cleopatra, which opened seven months after Bounty.

(Fox Home Video’s two-disc Cleopatra DVD has a doc that covers the making-of story in fascinating detail, and is actually much more engrossing and entertaining than the film.)

The DVD will also include a prologue and epilogue that was attached to the film for showings on TV in the late ’60s and/or ’70s, but never seen theatrically.

John Huston’s visual scheme for Reflections in a Golden Eye was created with cinematographer Oswald Morris, with whom he created the steely monochrome-ish color for Moby Dick and the rose-tinted, Toulouse Lautrec-ish color for Moulin Rouge.

It used a look of desaturated color with an emphasis on gold and pink. It was supposed to make you feel the perversity and the creepiness that permeates this adaptation of Carson McCullers’ novel, which is about a gay, heavily repressed Army Major (Brando) who ignores his hot-to-trot wife (Elizabeth Taylor) but has a thing for a hunky young private (Robert Forster).

The color succeeded in complementing the vaguely icky mood. Too well, I mean. Viewers complained that it made them feel queasy, and so the color reverted to conventional tones later in the run. The “normal” color also turned up on the VHS version that was sold way back when. WHV’s DVD of the gold-and-pink version will be the first time anyone has seen it in nearly 40 years.

The black-and-white Mutiny stills were sent to me by Roy Frumkes, a friend of restoration guru Robert Harris.

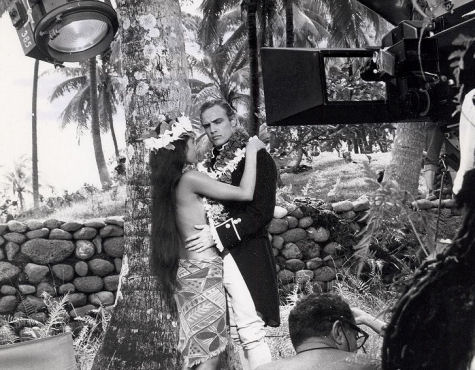

Tarita Teriipia, Brando shooting love scene. Tarita later had two children with Brando, including a troubled daughter, Cheyenne, who committed suicide in 1995.