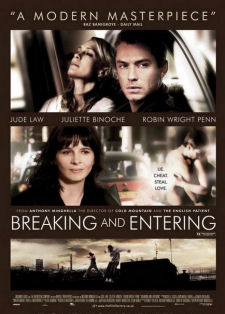

The ingredients in Anthony Minghella‘s Breaking and Entering (Weinstein Co.,12.15 in L.A.,1.27 limited) are explored and rotely disseminated in Sarah Lyall‘s 12.14 N.Y. Times profile piece. But here’s a fact that speaks volumes all on its own: Minghella’s mezzo-mezzo, not-bad drama is less than six weeks away from being seen in theatres, and the Weinstein Co. still doesn’t have a live website up and rolling to support it.

Minghella’s screenplay was inspired by his London studio flat having been repeatedly burgled three or four years ago when he was off making Cold Mountain in Roumania. Similarly, an office managed by a married architect (Jude Law) and his partner in London’s half-seedy, half-emerging King’s Cross district is repeatedly broken into and ripped off.

Law eventually spots the teenaged thief (Rafi Gavron), follows him home, and develops an immediate attraction for his Bosnian-refugee mom (Juliette Binoche). Curiously, despite Law’s well-known tabloid history and the fact that he may have portrayed one too many hounds over the past three or four years (Closer, Alfie), he and Binoche quickly sink into a steamy affair. As soon as it begins you can’t help but think, “Here we go again.”

Minghella is a major believer in volcanic currents between lovers, and it’s clear he feels more of an allegiance to Law’s affair with Binoche than Law’s marriage to a chilly Nordic blonde (Robin Wright Penn) who always seems vaguely pissed about something or other. There are no sex scenes between Law and Penn (naturally, given the nature of most marriages) but the action he shares with Binoche is intense and quite splendid. The fact that he gives her great oral sex seems to underline Minghella’s basic attitude, which is that he’s much more into exotic and uncertain alliances than steady and familiar ones.

Lyall says rather superficially that Breaking and Entering is about a “clash of cultures between the rich and the poor, the privileged and the disaffected, that churns beneath the surface of contemporary London.” This is certainly a part of it, but the movie eventually settles into a kind of guilty meditation piece that’s half about Law’s wandering penis and half about class disparity and liberal guilt.

Some people have been muttering that the film is inconclusive, half-“there” and indifferently off on its own beam. The biggest complaint is that it has a lousy ending, which it does. But it’s not a “bad”film, by which I mean it’s not, you know, boring. The performances by Law, Binoche, Gavron and Ray Winstone (as a detective) are more than absorbing for the most part, and the atmosphere seems recognizably “real.” But there’s not a lot of residue when you leave the theatre. The film does a fast fade in your head.