“I think the Vietnam War drove a stake right through the heart of America. [And] we’ve never really moved [beyond] that…we never recovered.”

I’ve been to Vietnam three times, and would love to return. I’ve even flirted with the idea or moving there permanently. There’s never been the slightest doubt in my mind that Johnson and Nixon administration policy makers brought immense horror and unimaginable slaughter to that beautiful, once-divided country.

But during my three visits I’ve never felt anything but the most tranquil vibes. Nobody has ever given me so much as a hint of a dirty look because of my heritage. The natives who fought against the Americans are, of course, in their 70s and 80s or passed on. The 45-and-unders weren’t even born during the hostilities. Nobody wants to carry that war around — we all want to live in the present.

Which is why I didn’t want to watch Ken Burns and Lynn Novick‘s The Vietnam War, a ten-part, $30 million, 17-hour doc about that tragic conflict, when it premiered on PBS almost exactly six years ago (9.17.17).

But last night…I don’t know why exactly, but I felt suddenly drawn to this miniseries. So I watched three episodes — “The River Styx” (January 1964 – December 1965), “This Is What We Do” (July 1967 – December 1967) and “Things Fall Apart” (January 1968 – July 1968). Five hours without a break. This morning I watched episodes #7, #9 and #10.

I was fascinated, fascinated, horrified, saddened, at times close to tears. What a deluge of death, delusion and horror. Immeasurable and irredeemable. The second most divisive war in U.S. history. And I couldn’t turn it off. Had to see it through. Glad I did.

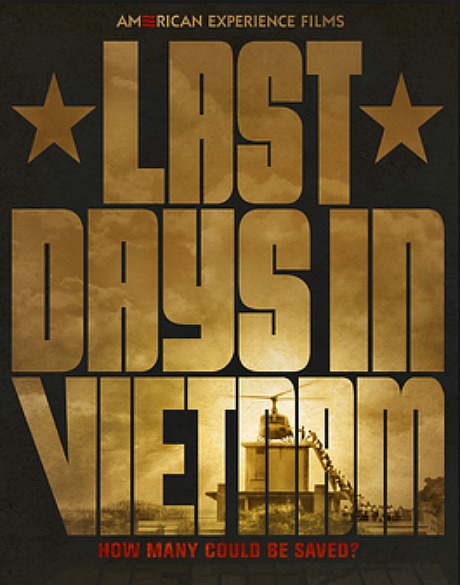

I felt profoundly moved and even close to choking up a couple of times while watching Rory Kennedy‘s Last Days in Vietnam yesterday at the Los Angeles Film Festival. The waging of the Vietnam War by U.S forces was one of the most tragic and devastating miscalculations of the 20th Century, but what happened in Saigon during the last few days and particularly the last few hours of the war on 4.30.75 wasn’t about policy.

For some Saigon-based Americans it was simply about taking care of friends and saving as many lives as possible. It was about good people bravely risking the possibility of career suicide by acknowledging a basic duty to stand by their Vietnamese friends and loved ones (even if these natives were on the “wrong” or corrupted side of that conflict) and do the right moral thing.

Last Days in Vietnam director Rory Kennedy during post-screening q & a.

Kennedy’s incisive, well-sculpted (if not entirely comprehensive) 98-minute doc is basically about how a relative handful of Americans stationed in Saigon — among them former Army Captain Stuart Herrington, ex-State Department official Joseph McBride and former Pentagon official Richard Armitage — did the stand-up, compassionate thing in the face of non-decisive orders and guidelines from superiors (particularly U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam Graham Martin) who wouldn’t face up to the fact that the North Vietnamese had taken most of South Vietnam by mid-April and would inevitably conquer Saigon. It was obvious as hell to almost anyone with eyes and ears, and yet Martin and other officials, afraid of triggering widespread panic, wouldn’t approve contingency plans for evacuation until it was way, way too late. So the above-named humanitarians and their brethren decided it was “easier to beg for forgiveness than to ask permission” and did what they could — covertly, surreptitiously, any which way — to save as many South Vietnamese as they could.

It was widely presumed that the advancing North Vietnamese would show no mercy to South Vietnamese who had collaborated with the Americans, so being left behind was all but tantamount to a death sentence. As it turned out between 65,000 and 200,000 South Vietnamese, according to information provided during last night’s post-screening q & a, were murdered by the North Vietnamese in the weeks and months after Saigon fell. (Some estimates run much higher).

It’s odd that a concluding epilogue in Kennedy’s doc declines to give any numbers on this score, not even a conservative estimate (provided by Herrington during the q & a) that at least 65,00 were killed. Kennedy said that the figure was hard to precisely determine and that she felt it was better to steer clear because of this statistical uncertainty. That struck me, no offense, as excessively cautious. Her film could have at least mentioned the lowball figure.

During the q & a I asked Kennedy why she didn’t include some North Vietnamese perspective from a military or political source who was involved in the struggle back then. Kennedy said she felt that including views from the North might dilute or needlessly complicate the simple vein of American heroism and compassion that the film was focusing on. She was also suggesting that perhaps voices from the opposing side wouldn’t be entirely candid about North Vietnam’s objectives and intentions regarding the South Vietnamese populace back then. But hearing from this side of the conflict would still round things out somewhat. The Vietnam War ended almost 40 years ago. All the veterans are old now, and people do tend to be a little more candid after the passing of a few decades. It wouldn’t have hurt to hear from a North Vietnamese veteran or two.

This American Experience-funded doc had its world premiere at Sundance last January. It will open theatrically in September and then air on PBS next April.

During my initial visit in Vietnam in late November 2012, I wrote the following after attending an opening-night party for the Hanoi Film Festival:

“I was standing in the upstairs hall and listening to Hoang Tuan Anht, Vietnam’s Minister of Culture, Sports and Tourism, give a speech about the aspirations of the festival and of Vietnam in general, and a thought occured. I looked around at the middle-aged men in tuxedos and women in beautiful ball gowns and various expats and guests amiably chatting and the waiters and busboys running around, and I thought to myself, ‘The United States fought a war and lost the lives of 58,000 men to stop this?’

“The people running this event are technically Communists and that was once a fearsome term to some, but who cares now? There was once reason to be concerned about the bureaucratic rigidity and corruption of a system dedicated to fighting capitalism but look at this country now, just trying to survive and prosper and get along. People are the same the world over. People change, societies adapt, money ebbs and flows, prejudice fades.

“The U.S. fought a ruinous and tragic war so that the fathers of the people currently running things in Vietnam could be prevented from unifying the country and, in the minds of the U.S. hawks and conservatives, from helping to perpetuate worldwide Communist domination, which was largely a myth from the start and in any case went out the window in 1989 and ’90. The left saw through the crap in the ’60s and early ’70s but now even the dimmest people in the world realize that the Vietnam War was an appalling and sickening tragedy caused by blindness and obstinacy and willful ignorance.”

Filed in late June 2016: Michael Herr, whose legendary 1977 novel “Dispatches” will always be the definitive grunt’s-eye, bong-hit chronicle of the Vietnam War — an Elements of Style-defying, darkly poetic, run-of-the-brain masterpiece — died Thursday at an upstate New York hospital, which may have been near his home in Delhi, where he lived for years. I was writing, packing and flying to New York that day (i.e., yesterday) so yeah, I was buried but I still feel a little badly that I didn’t catch the news until tonight. Michael Herr was the king of literary Vietnam, a guy who brought the shit home like no one had ever dared or imagined, who rock-and-rollicized the nightmare and the murdering and the war highs.

To me Herr was also the guy who sculpted much of Martin Sheen‘s voiceover narration for Apocalypse Now, although who knows who wrote what on that film? He also did some pinch-hitting on Full Metal Jacket. Herr was 76.

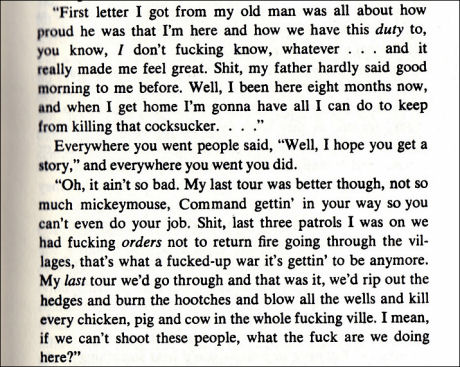

“‘Quakin’ and shakin’, they called it, great balls of fire, contact. Then it was you and the ground: kiss it, eat it, fuck it, plow it through with your whole body, get as close to it as you can without being in it or of it, guess who’s flying around about an inch above your head? Pucker and submit, it’s the ground. Under Fire would take you out of your head and your body too. Amazing, unbelievable, guys who’d played a lot of hard sports said they’d never felt anything like it, the sudden drop and rocket rush of the hit, the reserves of adrenalin you could make available to yourself, pumping it up and putting it out until you were lost floating in it, not afraid, almost open to clear, orgasmic death-by-drowning in it, actually relaxed.

“Unless of course you’d shit your pants or were screaming or praying or giving anything at all to the hundred-channel panic that blew word salad all around you and sometimes clean through you. Maybe you couldn’t love the war and hate it at the same instant, but sometimes those feelings alternated so rapidly that they spun together in a strobic wheel rolling all the way up until you were literally High On War, like it said on all the helmet covers. Coming off a jag like that could really make a mess out of you.” — page 63 of a dog-eared 1978 paperback version of Michael Herr‘s “Dispatches.” — “Vietnam Vietnam Vietnam, We’ve All Been There,” posted 12.29.15.

“Last night I bought a fresh new copy of Michael Herr‘s Dispatches — easily the best written and certainly the most important book about ground-level grunts during the Vietnam War bar none, renowned for its rich conveyance of the surreal climate and mentality and particularly the special lingo that went hand-in-hand with that whole jungle slaughterhouse experience.

“I bought it with the idea of persuading Jett to give it a read, which of course he refused to do after skimming the first two pages as we stood in the book store. Broke my heart, but every generation has its own way of seeing and processing, and of course writing about the things that matter, etc. I never liked Ernest Hemingway all that much when I was 21, certainly never as much as my father did. But I got into him later on. Across the river and into the trees.” — “The Carnage and the Grunts,” posted 6.12.09.