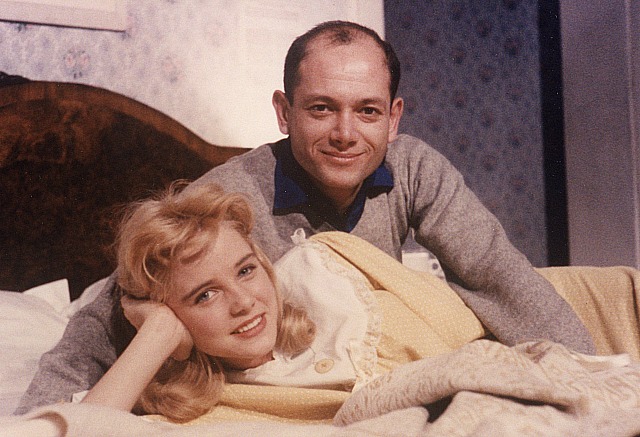

At age 92, producer-director James B. Harris is still with us. A longtime partner of Stanley Kubrick in the early days and a producer of Kubrick’s The Killing (’56), Paths of Glory (’57) and Lolita (’62), Harris also directed The Bedford Incident (’65), Fast Walking (’82) and Cop (’88).

And now comes disrepute — an allegation in a 10.24 Airmail piece by Sarah Weinman that Harris began an affair with Lolita star Sue Lyon when she was 14. Harris was 32 at the time.

The story was initially passed along by Mamas and the Papas singer Michelle Phillips, a childhood friend of Lyon’s. No one else has confirmed it. Weinman reached Lyon’s first husband Hampton Fancher, but he declined to comment. She also reached Harris but little came of it. Well, something did.

Weinman’s description: “Knowing I might not get another chance, I asked [Harris] straight out: Was he Sue Lyon’s first lover? ‘I’m just not going to talk about it,’ he said. It was a statement, without underlying emotion or self-reflection, not confirming but definitely not denying. Our conversation ended shortly thereafter.”

The allegation isn’t just that Harris crossed the perv line by having it off with a 14-year-old, but that the affair may have instilled a certain trauma in Lyon’s psyche.

Final paragraph: “There is no guarantee, with the level of mental illness in her family, that Lyon’s life would have stayed on course had she never made Lolita. But by doing so, Lyon became a clear example of art making a sucker out of a girl’s life, one whose price was too high to pay.”

Lyon money quote: “I defy any pretty girl who is rocketed to stardom at 14 in a sex nymphet role to stay on a level path thereafter.”