For the truly hip and attuned, the cosmic levitation and cultural changeover moment that was fanned by the mystical influence of Revolver and Sgt. Pepper lasted for only 18 months or so. As Terry Valentine later noted, “It was ’66 and early ’67…that’s all it was.” But for everyone else the playtime vibe was still happening, especially in the Hollywood realm during the spring-summer of ’69.

Everyone was coasting on be-here-now hedonism — a tingly roach-clip current, a sense of mystical whoa-ness and communal bliss — the last euphoric gasp of Woodstockian, LSD-propelled, Bhagavad Gita-tinged flower power before the bubble was popped by the Manson murders. And then, four months later, by the Altamont music festival killing.

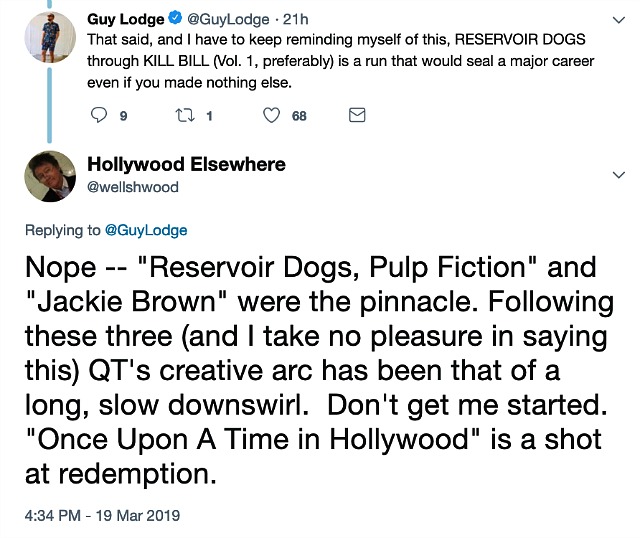

The just-released teaser for Quentin Tarantino‘s Once Upon A Time in Hollywood (Columbia, 7.26), which is set during the first few months of the Nixon administration but after the Mamas and the Papas had more or less split up (which makes the use of “Straight Shooter” on the trailer soundtrack seem odd), is about what the ’60s were like for mostly clueless Los Angeles fringe players. Atmospheric impressions of a dreamy, self-absorbed realm of gently stoned none-too-brights.

There are two versions of Leonardo DiCaprio‘s Rick Dalton in the trailer — a lean, traditionally coiffed, tidily dressed TV actor who danced on Hullaballo in ’65 or ’66 vs. a somewhat heavier, longer-haired, unshaven doobie toker of ’69.

The trailer contains an amusing exchange between Brad Pitt‘s Cliff Booth and Mike Moh‘s Bruce Lee.