Is there general agreement with my view that Jonathan Levine‘s 50/50 is an affecting, honestly configured drama ribbed or seasoned with occasional Rogen laughs (which you really need to call “yuks”) but is hardly a comedy, or do some feel that the term “comedy” actually, literally applies? What did the room feel like as it played? How old did the audience seem to be?

Daily

Magazines for Umbrellas

Last night’s New York Film Festival opener for Roman Polanski‘s Carnage went nicely, I thought. But it began raining fairly hard before the film began at 9 pm and was still coming down when the film ended just shy of 10:40 pm. There were no cabs in the rain, of course, so everyone took the IRT down to Times Square then walked four blocks over to the Harvard Club — slightly crouching, no umbrellas, somewhat exasperated expressions. My back felt as if someone had poured a glass of water onto my sport jacket. The party was great. The bull elephant head on the wall (the one allegedly shot by Teddy Roosevelt) looked green, for some reason.

Holding Action

Last night’s numbers (as reported by Deadline‘s Nikki Finke) had Moneyball in the #1 slot on its second weekend with a projected $12 million by Sunday night and a grand cume of $38 million. These days a 45% drop is considered a reasonably good second-weekend hold, but a mid 30% decline would have been more to my liking.

Dolphin Tale, which nobody in my sphere cares about, might wind up on top with an estimated $13 million…maybe. Courageous is being projected to come in third…blah.

If 50/50, which did $3.5 million last night, ends up with $9.5 million in 2458 situations, the per-screen average will be $3864. So by no means is it tanking, but audiences are being a little standoffish.

Nobody cares about Lion King 3D being expected to rake in $12 million by Sunday night with an estimated grand cume of $80.6 million. I mean, people “care” in the sense that they can’t ignore the huge success of this re-issue, but…fine, whatever, later.

Jim Sheridan‘s debuting Dream House, which wasn’t press-screened, did $2.7 million last night for an estimated weekend haul of $7.5 million. If that number holds it’ll have a per-screen average of $2817 in 2,661 situations. That’s bad.

Nobody cares about the seventh-ranked What’s Your Number? or ninth-place Abduction, but it’s moderately cool that Steven Soderbergh‘s low-key Contagion, beginning its fourth week of play, is still duking it out with an estimated $4.7 million of weekend income and an estimated cume of $64.4 million.

Ben-Hur Guys

I had intriguing discussions earlier today about the Ben-Hur restoration and Bluray with Warner Bros. mastering vp Ned Price and director Fraser Heston, and I recorded them even. But I have to get over to the New York Film Festival opening-night screening of Carnage and then the after-party at the Harvard Club, so the substantive Ben-Hur filing will have to wait.

Ned Price, vp mastering for Warner Bros. Technical Operations, earlier today at Manhattan’s Essex House — Friday, 9.30, 2:20 pm.

Director Fraser Heston, son of late Ben-Hur star Charlton Heston.

From master film restorationist/preservationist guru Robert Harris on Home Theatre Forum:

“Ben-Hur is a true restoration.

“The tracks sound more representative of the film than did those of the last DVD release, which seemed heavy on the effects, the color is back, and very representative of the look of the original. The Glory Days of Ben-Hur have returned.

“Everything looks to have been dutifully handled, and the recipient of all of this work is the home theater enthusiast.

“Ben-Hur is a glorious Blu-ray experience. The labors performed to get it back into shape look superb on the format. Some will discuss the aspect ratio. Filmed at 2.76:1, I’m happy with it anywhere between 2.5 and 2.76. I don’t believe that it matters. In over 200 minutes of film, I noted no major problems. A couple of mis-cuts, which will never be noticed. Even dupes are handled to perfection.

“The icing on this particular release is inclusion of the tinted and two-color 1925 silent version, from Photoplay, and with a score by Carl Davis. A silent masterpiece in its own right.

“I must make the point. The way to see properly this film is on a huge screen, but in the world of home theater and Bluray, Warner Home Video’s new Ben-Hur is Very Highly Recommended, and looks to be the major restoration to hit Bluray in 2011. The quality of the film shines through.”

"Liberal Plantation"

When Herman “the Hermanator” Cain said two days ago that African-American voters vote overwhelmingly liberal due to “brainwashing and people not being open-minded, pure and simple,” he was stating a basic fact. Substitute “brainwashing” for “cultural conditioning” and he was describing how most of us are shaped by our native cultures, at least in our youth. There are specific reasons for African-American political allegiances that don’t apply to some of us, but we’re all “brought up” to think and vote in a certain way.

I was conditioned to be a liberal because of the left-liberal views of my parents and the left-liberal values of Westfield, New Jersey, and Wilton, Connecticut, where I was living when I figured out what my cutural and political values were. We’re all conditioned to think and assess the world as we were taught by our parents and our extended neighborhood family. It’s a rare bird who goes out into the world and makes his/her fortune and decides to think and vote in a radically different way than what he/she taught in his/her formative years.

That said, the Hermanator is dreaming if he thinks African Americans are going to leave the “liberal plantation,” as MSNBC’s Pat Buchanan crudely put it earlier today.

Up The Flagpole

In one fell swoop, Hollywood Elsewhere has significantly altered the imbalance between the greedy haves and the desperate have-nots. By going down to Zuccotti Park (Broadway and Liberty Street) this afternoon and taking pictures of the Occupy Wall Street crowd and posting them, I’ve…well, at least helped somewhat. Storm the barricades!

Certainly These

Jonathan Levine‘s 50/50 and Jeff Nichols‘ Take Shelter are far and away the best new films to see this weekend.

But please understand that 50/50 is not a comedy, despite what Lou Lumenick and others are saying.

I explained it thusly earlier this month: “All mature art is mixture of drama and comedy. Any film that insists on being a drama-drama or a comedy-comedy doesn’t get this. Life is always a mixture of the two, and so naturally 50/50 is flecked or flavored with guy and gallows humor here and there plus one or two anxious-mom jokes and/or chemo jokes and/or jokes about being in denial, etc. The most you could say is that it’s amusingly jaunty at times. It’s good humored and good natured when the material calls for that…when it feels right and true.

“And any critic who knows quality-level filmmaking when he/she sees it is going to recognize that humor is definitely a part of the package, definitely an element.”

Zuccotti Park

It doesn’t matter if Occupy Wall Street (which has expanded to Boston and San Francisco and elsewhere) is lacking a specific goal, or if it feels unfocused or futile or whatever. The fact that a miniscule speck of GenY anger is being expressed is at least something. Or…you know, is better than watching Jimmy Kimmel. Any expression of dismay or loathing or rage about the sociopathic stacked-deck, rich-favoring U.S. economy led and exploited by the Wall Street machine gets my vote. That’s why I’m going down there this afternoon…yeah!

My Own Guy

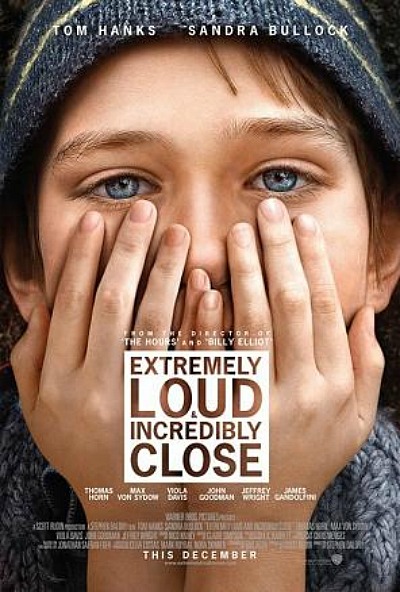

I spoke last night to a guy who caught a research screening of Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close last Sunday night at Leows’ Lincoln Square (B’way at 68th). And he agrees with Kris Tapley’s guy that Max Von Sydow‘s wordless performance as Thomas Horn‘s grandfather “will certainly get an Oscar nomination, perhaps the award itself.”

And he has a slight dispute with Stu Van Airsdale’s guy about the opening with “falling bodies, crushing thuds, and other vividly horrifying reminders of the initial scene at the World Trade Center.” My guy’s dominant impression is “an obliquely falling body in a white suit. If this wasn’t a 9/11 film, it could easily be mistaken for a Cirque Du Soleil routine.”

“One surprising thing about the film,” he adds, “is that James Gandolfini, credited in both the trailer and the poster, has had his role entirely cut. John Goodman‘s role is reduced as well, adding up to a few short scenes.” I don’t know how he’d know that Goodman’s role has been reduced unless he’s read a draft of Eric Roth’s script or whatever. I forgot to interrogate about this.

“And as for all those folks that pointed out that there’s snow on the ground in a few scenes in the trailer, it’s important to note that the film takes place a few years after 9/11; those scenes aren’t meant to reflect 9/11.” But of course the trailer, despite the MD80 thing, is looking to evoke precisely that.

Still "Too Soon"?

Movieline‘s Stu Van Airsdale has spoken to a guy who’s allegedly seen Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, and one of his reactions, Van Airsdale writes, is that “the film’s current introduction — which features falling bodies, crushing thuds, and other vividly horrifying reminders of the initial scene at the World Trade Center — was less emotionally affecting than just inappropriate” and “too soon.”

Ten years later is too soon? I got fairly angry with people who were saying this five years ago when United 93 was about to open, but anyone who says this now is taking the post-traumatic thing into obsession. “Too soon!” is the mantra of people who aren’t breathing in and out, who are basically coming from a place of emotional denial or suppression. I have eight words for Van Airsdale’s guy: It happened, life moves on, get over it.

Put another way, if you shudder and moan for too long in response to a given traumatic event, if you refuse to heal and accept the natural shedding of skin, there comes a point when people start regarding you as a grief monkey.

For What It's Worth

I think that the close-up image of Thomas Horn in the Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close poster is oddly intriguing. Hands to the face means shock or alarm, but Horn’s eyes are laid-back, almost serene. He could be listening to a lecture by a teacher or watching a TV show or staring at a sleeping cat. An opaque expression in the midst of heavy drama about 9/11 and death and whatever else…cool.