Cody Jarret to Hezbollah: “Come and get me, ya dirty…”

…you’re either (a) a reasonable humanitarian or (b) almost certainly an anti-Semite.

David Leitch will never be forgiven for having directed Bullet Train…never. The ex-stunt man’s other directing offenses include Atomic Blonde (’17) and Deadpool 2 (’18). Imagine being Leitch himself and being stuck 24/7 in the fucking chowderhead head of his…God.

The Fall Guy pops on 3.1.24.

Last night I ordered a modestly priced Caesar Salad at Orem’s Diner, but for some reason my appetite faded. So I brown-bagged it, brought it home, put it in the fridge. My plan this morning was to do a wash at the Wilton Laundromat and then hit the library or the River Road Starbucks for the usual arduous filing.

So I grabbed my loaded-down leather computer bag, my bright-red laundry bag, a plastic container of Tide and the clear plastic Ceasar Salad container, and carried it all to the the car. I put the Caesar on the car roof while loading the back and front seats. No hurry, nice and careful. I started the engine, backed the car out and headed south to the laundromat.

It wasn’t until this evening around 7 pm that I realized what had happened with the Ceasar. I’m figuring it held on for two or three minutes as I drove along the winding country roads, but once I hit the gas on Route 7 the wind blew it off and the plastic container with all that Romaine lettuce and those chicken chunks and cherry tomatoes splattered and scattered big-time…it couldn’t have been a pretty sight.

I’m imagining what the person driving behind me must have thought: “God, will ya look at that absent-minded asshole?…he probably doesn’t even know what’s happened…who’s going to pick this mess up?…what if some hungry deer tries to eat some of the lettuce and chicken and some guy driving and texting isn’t paying sufficient attention?”

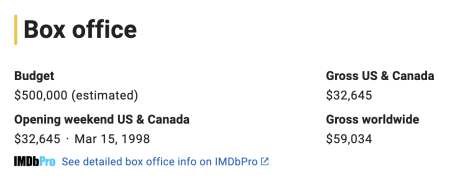

Several years ago Entertainment Weekly critic Owen Gleiberman wrote that Martin Scorsese‘s “volcanic” Mean Streets — one of the greatest debut efforts of all time if you don’t count Who’s That Knocking On My Door? and Boxcar Bertha — “barely made pocket change back in 1973, [having] grossed all of $3 million.”

In fact, both IMDB Pro and thenumbers.com report that Mean Streets grossed $32,645 domestic (U.S. and Canada) and somewhere in the vicinity of $59,034 worldwide. The Numbers actually reports that the global take was $50,539.

…and I can’t even play guitar. Just listening to John Lennon‘s vigorous strumming gives my right hand a feeling of rigor mortis. Paul McCartney has said that Lennon’s strenuous guitar work made this song come together.

Variety‘s Matt Donnelly is reporting that September ’22, the late Lisa Marie Presley sent a pair of scathing, straight-from-the-shoulder emails to directior-writer Sofia Coppola about the not-yet-shot Priscilla, which she’d read a script for.

“My father only comes across as a predator and manipulative,” Lisa Marie wrote. “As his daughter, I don’t read this and see any of my father in this character. I don’t read this and see my mother’s perspective of my father. I read this and see your shockingly vengeful and contemptuous perspective, and I don’t understand why.”

Presley told Coppola that she would speak out against the project and her mother, Priscilla Presley, whose semi-imprisoned existence under the thumb of Elvis Presley between ’59 and sometime in the late ’60s is the subject of the film.

I won’t be seeing Priscilla until tomorrow. Has anyone seen it, and what’s your take? Was Elvis really as malevolent and fucked up as the film allegedly maintains? Coppola’s film also depicts the king of rock ‘n’ roll as Paul Bunyan-sized.

Jordan Ruimy: “Sadly, Priscilla does make Elvis look like a real jerk. Elvis is portrayed as an arrogant womanizer; soft at one moment, turbulent hound dog the next.”

While writing my Glenn Howerton piece it occured to me that 24 Gold Derby handicppers members are predicting a Best Supporting Actor supporting nomination for Robert DeNiro‘s “King” Hale in Killers of the Flower Moon.

This is actually a hugely annoying performance and doesn’t begin to deserve an Oscar nomination…get outta here! As I said in the piece, Bobby D’s twangy accent and repetitive dialogue gave me a headache when I saw Martin Scorsese’s film for the second time.

This gave me the idea of listing the DeNiro performances (less than 30) that are 100% guns blazing, completely non-problematic and absolutely unimpeachable. Here they are…the extra-special perfs are in boldface…and I’m not cutting him any slack by mentioning pretty goods and okays…this list is strictly about stellar and super-stellar.

28 standouts over a 53-year period….eight solid goldies in the ’70s, eight in the ’80s, eight in the ’90s and four in the 21st Century — we all know that DeNiro has made a significant number of shit-level movies since 9/11.

Greetings (’68) and Hi, Mom! (’70)….DeNiro playing the same character (Jon Rubin)

Bang the Drum Slowly (’73)

Mean Streets (’73)

The Godfather Part II (’74)

Taxi Driver (’76)

1900 (’76)

The Deer Hunter (’78)

Raging Bull (’80)

True Confessions (’81)

The King of Comedy (’83)

Once Upon a Time in America (’84)

Falling in Love (’84)

Angel Heart (’87)

The Untouchables (’87)

Midnight Run (’88)

Goodfellas (’90)

Mad Dog and Glory (’93)

This Boy’s Life (’93)

A Bronx Tale (’93)

Heat (’95)

Jackie Brown (’98)

Ronin (’99)

Analyze This (’99)

Meet the Parents (’00)

Silver Linings Playbook (’12)

The Intern (’15)

The Irishman (’19…forget the flawed CG aging aspect…the performance itself is the stuff of legend)

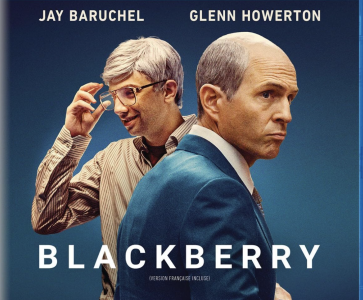

When Matt Johnson‘s BlackBerry opened last May, the instant consensus was that Glenn Howerton‘s turn as former BlackBerry honcho Jim Balsillie, a deliciously hard-nosed and at times ruthless operator, was the stand-out.

It naturally follows that Howerton, costar of FX’s long-running It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia and a guy who radiates his own amusing edge vibes in interviews, deserves to be nominated for Best Supporting Actor. Hell, he deserves to win.

Of course he does! Because Howerton is the guy you remember when you come out of BlackBerry, and the force-of-nature actor who makes you chuckle despite Balsillie’s prickish personality.

“I would admit that I gravitate towards men who seek power,” Howerton says in a BlackBerry promo video. “As far as Jim is concerned, he wants to be perceived as the smartest guy in the room. Which masks the fear and insecurity that he’s not. I think he is driven by that fear.”

As we speak there are three Gold Derby spitballers — Collider’s Perri Nemiroff, IMDB’s Keith Simanton, Gold Derby’s Tariq Khan — who agree with me. And Khan has Howerton at the top of his list!

(Believe it or not 24 GD members are predicting a supporting nom for Robert DeNiro‘s scheming one-note scumbag in Killers of the Flower Moon…seriously? Bobby D’s twangy accent and repetitive dialogue gave me a headache when I saw Martin Scorsese’s film for the second time.)

Another feather in Howerton’s cap is the absolute requirement that at least one Oscar-aspiring supporting performance must hail from the indie sector.

On top of which Howerton’s Balsillie isn’t just funny but comforting. To my slight surprise I immediately liked his baldy baldass because of the three main BlackBerry characters Basillie is the only tough-nut adult — brusque and flinty with an explosive temper, okay, but at least he’s a realist, which is more than you can say for Jay Baruchel‘s Mike Lazaridis and Johnson’s Doug Fregin, or at least how they’re portrayed.

During the first half Baruchel and especially Johnson overplay the nerd-child behavior. They’re a pair of precocious, inarticulate twits living in their own world. But then along comes the cut-the-shit-and-get-organized Basillie, and you go “thank God!…a brass-tacks suit who knows how to handle himself in corporate circles, and a guy who will tell Lazaridis and Fregin to shut up whenever they start talking like 13-year-olds.”

There are actually two humorous hardnosed-prick performances that are competing for finalist status — Howerton’s and Chris Messina‘s excitable agent David Falk in Air. I just had a much better time with Howerton.

There’s another Oscar-burnishing quality that Howerton’s performance brings — he altered his appearance by shaving his head. (Or he wore one of those bald caps…whatever.) Any SAG-AFTRA member will agree that going bald is an equivalent of Robert DeNiro gaining 70 pounds for Raging Bull (resulting in a win) or Nicole Kidman wearing a prosthetic nose in The Hours (ditto).

On top of which Howerton’s performance will soon be back in the spotlight when a three-episode version of BlackBerry will begin airing on Monday, 11.13. The miniseries will include 16 minutes of never-before-seen footage. The feature version ran 159 minutes and yet each AMC episode will run for 60 minutes, or roughly 180 minutes.

Glenn Howerton’s abrasive bossy-boots behavior rules the 21st Century!…not since Kevin Spacey‘s Buddy Ackerman in George Huang‘s Swimming With Sharks (’94)!

Variety‘s Courtney Howard and The Hollywood Reporter‘s Frank Scheck have reviewed Meg Ryan‘s What Happens Later (Bleecker Street, 11.3), an older person’s romcom set in a snowbound airport, and based upon Steven Dietz’s play Shooting Star.

Apart from noting that it’s a two-hander and agreeing upon the magical realist atmosphere, the disparity of opinion is startling.

Scheck: “Not so much a romcom as a comic drama infused with strong doses of magic realism that some viewers will find charming and others insufferably twee. What might have proved effective theatrically comes across as wholly artificial and schematic onscreen, despite Ryan’s considerable efforts as both director and performer. The proceedings inevitably feel claustrophobic. While Ryan’s bountiful charm is as evident as ever, her character unfortunately comes across like an older version of the manic pixie dream girl. And the movie’s heavy-handed magical realist elements counter the slightness of the material to deadly effect.

Howard: “Meg Ryan not only dazzles before the camera in What Happens Later, but behind it as well, as director and co-writer. Through the prism of one former couple’s relationship woes, this effervescent, enlightened romantic comedy explores our innate need for reconciliation within ourselves and with each other. It’s a delight to welcome Ryan back to the silver screen after an extended hiatus, and in the genre she helped rejuvenate alongside filmmakers like Rob Reiner and Nora Ephron (to whom this film is touchingly dedicated).”

I haven’t seen What Happens Later, but Howard’s use of the term “touchingly dedicated” almost certainly indicates bias. She’s in the tank for romcoms, I suspect, and loves the idea of Ryan making one of her own.