Not to mention that nightmare of a lampshade.

Last night I caught Craig Gillespie‘s Dumb Money (Sony, 9.15), which had its big premiere in Toronto a few days ago.

It’s based upon Ben Mezrich‘s “The Anti-Social Network“, a 2021 non-fiction account of the GameStop short squeeze, which principally happened between January and March ’21.

The key narrative focus, of course, is class warfare.

Dumb Money is a Frank Capra-esque tale of a battle of influence between financially struggling, hand-to-mouth Average Joe stock investors vs. elite billionaires who tried to reap profits out of shorting GameStop.

The legacy of the 2008-through-2010 recession and movies like Margin Call (’11), The Wolf of Wall Street (’13) and The Big Short (’15) resulted in considerable hostility towards Wall Street hedge fund hotshots.

The venting of this anger was enabled by the ability of hand-to-mouth, small-time traders keeping up with fast market changes through social media investment sites like R/wallstreetbets.

I’m too dumb to fully understand the intricacies of the term “short squeeze**,” but I understand the broad strokes.

I didn’t love Dumb Money, but I paid attention to it. It didn’t exactly turn me on but it didn’t bore me either. I didn’t once turn on my phone. I was semi-engaged.

Paul Dano‘s performance as Keith Gill, the main stock speculator and plot-driver, is fairly compelling. The costars — Pete Davidson, American Ferrara, Seth Rogen, Vincent D’Onofrio, Nick Offerman, Anthony Ramos, Sebastian Stan and Shailene Woodley — deliver like pros.

I spent a fair amount of time wondering why the 39 year-old Dano is heavier now than he was as Brian Wilson in Bill Pohlad‘s Love and Mercy, for which he intentionally gained weight. The real Gill is semi-slender or certainly not chubby.

Clearly Margin Call, The Big Short and The Social Network have far more pizazz and personality.

** “A short squeeze is a rapid increase in the price of a stock owing primarily to an excess of short selling of a stock rather than underlying fundamentals. A short squeeze occurs when there is a lack of supply and an excess of demand for the stock due to short sellers having to buy stocks to cover their short positions”…huh?

I’ve been wondering about the curious absence of Black Flies (Open Road, 11.30) since its 5.18.23 debut in Cannes.

It may not be a great, game-changing film or what any fair-minded viewer might call piercing or compassionate or startlingly original, but I for one decided right away that it’s a more absorbing dive into the lives of living-on-the-ragged-edge paramedics than Martin Scorsese‘s Bringing Out The Dead (’99).

Like it or not, this is my opinion and I’ve no intention of modifying or watering it down.

Based on a drawn-from-hard-experience 2008 novel of the same name by Shannon Burke, adapted by Ryan King and Ben Mac Brown and directed by Jean-Stéphane Sauvaire, Black Flies didn’t deserve a 47% Rotten Tomatoes rating.

It stars Sean Penn, Tye Sheridan, Katherine Waterston, Michael Pitt, Mike Tyson and Raquel Nave.

In a 5.25 assessment of the Cannes Film Festival (“At a Particularly Strong Cannes Film Festival, Women’s Desires Pull Focus“), N.Y. Times critic and gender celebrationist Manohla Dargis not only dismissed Black Flies but called it “ridiculous.” That means it made her angry.

Dargis wasn’t alone. A significant percentage of Cannes critics ganged up on Black Flies due to what they saw as an overly unsympathetic view of Brooklyn’s primitive, ragged-edge underclass.

Film Verdict‘s Jay Weissberg accused it of being “tone-deaf” and hampered by a “problematic treatment of immigrant communities and women.”

Translation: Some critics detected a certain callousness flecked with racism and sexism. I found that view simplistic and ridiculous.

HE verdict, posted on 5.19: “It beats the shit out of you, this film, but in a way that you can’t help but admire. It’s a tough sit but a very high-quality one. The traumatized soul of lower-depths Brooklyn and the sad, ferociously angry residents who’ve been badly damaged in ways I’d rather not describe has never felt more in-your-face.

“In terms of assaultive realism and gritty authenticity Black Flies matches any classic ’70s or ’80s New York City film you could mention…The French Connection, Serpico, Prince of the City, Q & A, Good Time, Across 110th Street.

“And what an acting triumph for Sean Penn, who plays the caring but worn-down and throughly haunted Gene Rutkovsky, a veteran paramedic who bonds with and brings along Tye Sheridan‘s Ollie Cross, a shaken-up Colorado native who lives in a shitty Chinatown studio and is trying to get into medical school.

“Rutkovsky is a great hardboiled character, and Penn has certainly taken the bull by the horns and delivered his finest performance since his Oscar-winning turns in Mystic River (’03) and Milk (’08).

“And Sheridan is also damn good in this, his best film ever. His character eats more trauma and anxiety and suffers more spiritual discomfort than any rookie paramedic deserves, and you can absolutely feel everything that’s churning around inside the poor guy.

“At first I thought this 120-minute film would be Bringing Out The Dead, Part 2, but Black Flies, which moves like an express A train and feels more like 90 minutes, struck me as harder and punchier than that 1999 Martin Scorsese film, which I didn’t like all that much after catching it 23 and 1/2 years ago and which I’ve never rewatched.

The more I read about Christy Hall‘s Daddio, the sorrier I am that I ducked it in Telluride. I was especially persuaded by Todd McCarthy’s Deadline review. I’m very much looking forward to the next viewing opportunity.

Pic is a two-hander about a grizzled New York City cab driver named Clark (Sean Penn) covering the verbal and cultural waterfront with his blonde 30something passenger (Dakota Johnson).

I should admit there was a specific reason why I didn’t see Daddio last week. It was because of the dopey Millennial spelling. If it had been spelled right I would have gone in a heartbeat.

Daddy-o is a beatnik anachronism. The root term (duhh) is “daddy” with a “y”. Daddio is for dingleberries.

Among the leather jacket-wearing, Marlon Brando wannabe set in the 1950s “hey, dad” was a term of respectful affection…a cool familiarism.

In the 1960 jukebox tune “Alley Oop” (written in ’57, released in ’60) the phrase “king of the jungle jive” is rhymed with “ride daddy ride.”

In Brando’s One-Eyed Jacks (’61) Karl Malden‘s character is named “Dad” Longworth — a nickname that ignores western culture in deference to ’50s be-bop sensibilities.

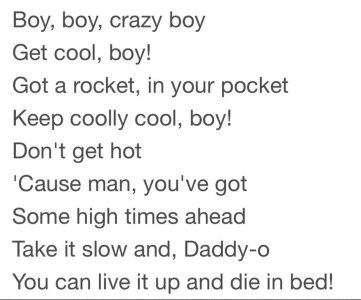

In Stephen Sondheim‘s lyrics for “Cool,” the West Side Story song, it’s spelled “daddy-o”

In the real-deal world of rebellious Rebel Without A Cause-era attitudes, there were never any “daddios.” It was daddy-o or nothing.

I’m trying to imagine being Jack Antonoff, a wealthy, super-successful, top-of-the-world, Grammy Award-winning musician and record producer (not to mention a highly valued Taylor Swift and Lorde collaborator and a recently betrothed husband of Margaret Qualley)…I’m trying to imagine having so much of the world figured out and having audaciously influenced contempo pop music over the last decade or so…

I’m trying to imagine being Antonoff in his bedroom and deliberately choosing to wear a standard low-rent basketball bruh outfit (baggy NBA-brand shorts, black Darold T-shirt, shamrock green cap, sneakers and white socks) and thereafter walking out onto the streets of New York City on his way to Whole Foods and saying “yeah, no sweat, of course.”

Rich or poor, ugly or handsome, famous or obscure, I wouldn’t wear this kind of low-rent outfit with a knife at my back. Goons could hold me down on the bedroom floor and say “wear this crap or you’re dead” and I’d snarl and say “go fuck yourselves”…and yet guys like Antonoff are like “yeah, man…this kind of sartorial signature really does it for me…blends with who I am, what I feel deep down”… imagine Cary Grant weeping in heaven…even the ghost of James Dean would say “the fuck?”

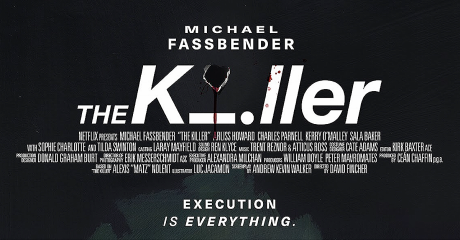

“The driving idea of The Killer is that Michael Fassbender’s hit man, with his cool finesse, his six storage spaces filled with things like weapons and license plates, his professional punctiliousness combined with a serial killer’s attitude (the opening-credits montage of the various methods of killing he employs almost feels like it could be the creepy fanfare to Se7en 2), has tried to make himself into a human murder machine, someone who turns homicide into a system, who has squashed any tremor of feeling in himself.

“Yet the reason he has to work so hard to do this is that, beneath it all, he does have feelings. That’s what lends his actions their moody existential thrust. At least that’s the idea.

“But watching the heroes of thrillers act with brutal efficiency (and a total lack of empathy for their victims) is not exactly novel. It’s there in every Jason Statham movie, in the Bond films, you name it.

“The Killer is trying to be something different, something more ‘real,’ as if Fassbender were playing not just another genre character but an actual hitman. That’s why he has to use a pulse monitor to make sure his heartbeat is down to 72 before he pulls the trigger. It’s why he’s hooked on the Smiths, with their languid romantic anti-romanticism. As catchy a motif as that is, you may start to think: If he’s such a real person, doesn’t he ever listen to music that’s not the Smiths?

“In The Killer, [director] David Fincher is hooked on his own obsession with technique, his mystique of filmmaking-as-virtuoso-procedure. It’s not that he’s anything less than great at it, but he may think there’s more shading, more revelation in how he has staged The Killer than there actually is.” — from Owen Gleiberman’s 9.3 review.

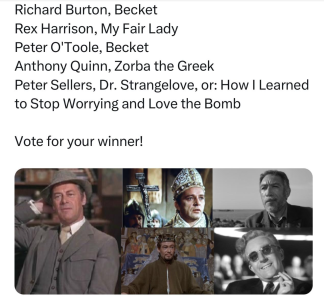

The long-established consensus is that Rex’s Harrison Best Actor Oscar for his My Fair Lady performance was, at the very least, unfortunate, particularly given the calibre of the competition — Peter O’Toole and Richard Burton in Becket, Anthony Quinn in Zorba the Greek, and Peter Sellers‘ trio of performances in Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

Since Becket hit Bluray in ’08 pretty much everyone began to realize that King Henry II was O’Toole’s peak role and performance, and that he was robbed. Or so it seemed. But according to a Twitter poll I saw this morning, the majority feels it was actually Sellers who was robbed.

My presumption is that everyone has seen Strangelove and relatively few have seen Becket, and there’s not much more to it than that.

Sellers is magnificent in Strangelove, of course, but playing three characters in a single film (if not for an injury he would’ve played four) is essentially a stunt, plus none of his characters really touch bottom, especially given the film’s darkly satiric tone. They were three sketch bits, not full-bodied performances.

And of course, strategy-wise Paramount publicists pushing O’Toole and Burton equally was all but guaranteed to result in a loss for both.

I can’t pound out a ten-paragraph review of Yorgos Lanthimos‘ Poor Things as it’s nearly 11 pm and I’m really whipped (I only slept about four hours last night) but it’s totally fucking wild, this thing — it’s too sprawling to describe in a single sentence but I could start by calling it an imaginatively nutso, no-holds-barred sexual Frankenstein saga.

The production design and visual style are basically pervy Lathimos meets Terry Gilliam meets Jean Pierre Juenet…really crazy and wackazoid and fairly perfect in that regard.

Set in a make-believe 19th Century realm that includes fanciful versions of London, Paris and Lisbon, Poor Things is at least partly The Bride of Frankenstein by way of a long-haul feminist parable about a underdog woman eventually finding strength and wisdom and coming into her own.

It swan-dives into all kinds of surreal humor with boundless nudity and I-forget-how-many sex scenes in which Emma Stone, giving her bravest and craziest-ever performance, totally goes to town in this regard save for the last, oh, 20 or 25. The film runs 141 minutes.

Poor Things is easily Lanthimos’ finest film, and all hail Stone For having gone totally over the waterfall without a flotation device…giving her boldest, most totally-out-there performance as she rides the mighty steed, so to speak, while repeatedly behaving in a “big”, herky-jerky fashion as Tony McNamara’s screenplay, based on Alasdair Gray‘s same-titled novel, whips up the perversity and tests the boundaries of what used to be known as softcore sex scenes.

The costars include Mark Ruffalo (giving a totally enraged, broadly comic performance as a middle-aged libertine), Willem “Scarface” Dafoe as Dr. Godwin Baxter, Ramy Youssef as Dafoe’s assistant and Christopher Abbott as as an upper-class London slimeball, plus four stand-out cameos by Margaret Qualley, Kathryn Hunter, Suzy Bemba and 79-year-old Hanna Schygulla.

I’ll add to this tomorrow morning but this is one serious boundary-pusher…wow.

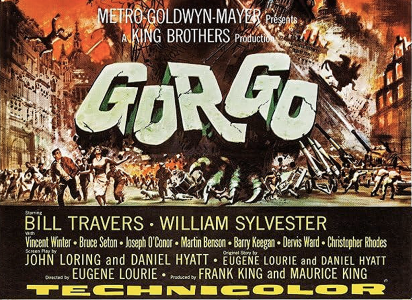

The late William Sylvester (1.31.1922 – 1.25.95) became a semi-legendary figure when he played Dr. Heywood R. Floyd, the smug and officious National Council of Astronautics official from 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Almost a comically flavorless and dull-minded bureaucrat, Floyd didn’t do or say much — he just flew up from earth to visit Clavius, the moon base, to see about the recently discovered black monolith that had been “deliberately” buried under the moon’s surface some four million years earlier.

One other significant role that Sylvester played was in Gorgo (’61). Sylvester portrayed Sam Slade, a seafaring adventurer of some sort who, along with Cpt. Joe Ryan (Bill Travers), captures Baby Gorgo, a huge prehistoric reptile who is brought to London for public exhibition. Everything seems fine until Ma Gorgo — a much, much larger beast — visits and trashes the city in order to save her son.

I’ve never seen Gorgo but my understanding is that it’s a tolerable mønster flick, but generally second tier. I’m thinking of Sylvester because a new Gorgo Bluray is currently for sale.

…that Colman Domingo‘s performance as Bayard Rustin in Rustin (Netflix, 11.3) will be a bold-as-brass, James Baldwin firecracker-type thing (which the trailer suggests), it seems to me that a film about an historical civil-rights-movement leader who was both Black and gay…that’s two checked boxes right there…plus a film that was launched by Barack and Michele Obama‘s Higher Ground Productions…that’s a third box-check given the urge to show obeisance to the Obamas within liberal circles, etc.

Should we give the possessory credit to the Obamas or director George C. Wolfe?

During his second term in the White House, Barack posthumously awarded Rustin with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. At the 11.20.13 ceremony, Obama presented the award to Walter Naegle, Rustin’s surviving longtime romantic partner.

The almost entirely all-black cast includes Chris Rock as Roy Wilkins and Jeffrey Wright as Rep. Adam Clayton Powell.

Rustin will have its first-anywhere debut at Telluride. If Barack and Michelle don’t fly in and take a few bows, the troops will be bitterly disappointed.

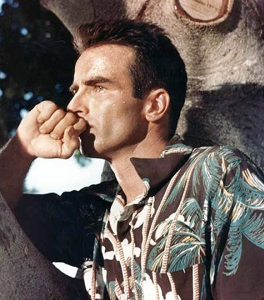

…and a black floral-print shirt (fairly similar to Montgomery Clift‘s Hawaiian-style shirt that he wore in From Here to Eternity) under what looks like a Brian DePalma safari jacket.

I respect and admire the blending of a noir palette with a watercolor effect, which may have been achieved via standard photo manipulation using Average Joe software…the kind you can buy on any iPhone.

David Fincher‘s The Killer premieres at the Venice Film Festival on Sunday, 9.3 — six days hence. It will open in “select” theatres on Friday, 10.27. The Netflix debut happens on Friday, 11.10.

Marketing tag line: “After a fateful near miss an assassin battles his employers, and himself, on an international manhunt he insists isn’t personal.”

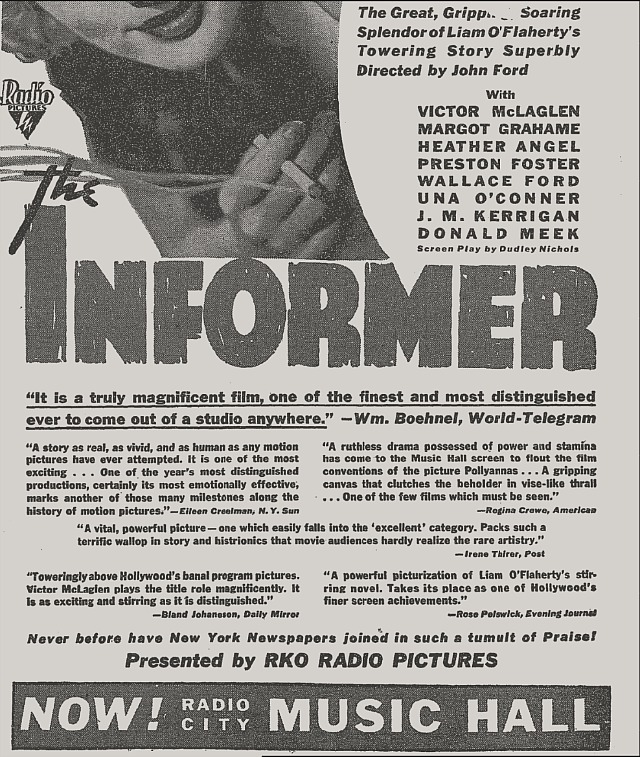

This evening I tried again with John Ford‘s The Informer> (’35), and in so doing experienced something like an epiphany. It surprised the hell out of me, but there was no mistaking what I was feeling. For the first time I accepted the foolishness and rank idiocy of Victor McLaglen‘s Gypo Nolan — surely one of the most loathsome lead characters in movie history, and a pathetic, bellowing drunk to boot.

For the first time I cut Gypo a break and took off my black hooded mask.

My first viewing….good God, Ford’s classic is 88 years old now…my first viewing (late-night TV, possibly WOR-TV) happened when I was ten or eleven, something like that; my most recent before tonight was 20 years ago.

I’ve never felt anything but admiration for the various elements — McLaglen’s Oscar-winning lead performance, Dudley Nichols‘ finely-chiselled screenplay (the film only runs 91 minutes), the magnificent fog-shrouded cinematography by Joseph August (Twentieth Century, Gunga Din,The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Portrait of Jennie), Max Steiner‘s haunting score and the supporting performances by Margot Grahame, Heather Angel, Preston Foster, Una O’Connor and Joe Sawyer.

It all fuses together so well, but all my life I’ve had a hugely difficult time with the deplorable Gypo. And yet something happened this time. Something ineffably sad that found its way inside. By the end I felt so sorry for this poor alcoholic idiot that I was strangely unable to despise him. I could only shake my head in sorrow.

And that final church scene after he’s been shot four or five times in the gut, bleeding to death…that scene got me all the more. When Gypo stumbles into a church and finds Frankie’s mother (Merkel) and says with that pleading, nearly whispering, wounded-ox voice, “Twas I who informed on your son, Mrs. McPhillip…forgive me.” And the poor woman does for some reason, and then comforts him with “you didn’t know what you were doin’.” Gypo stands and spreads his arms before a crucifix, calls out to the man he betrayed and condemned to a brutal death (“”Frankie! Your mother forgives me!”), clutches his midsection, drops to the church floor and dies.

If I’d been Mrs. McPhillip I would have said, “You’ll get no forgiveness from me, Gypo. And from the looks of you, you won’t be needing any soon. Just let go…just let it go. There’s nothin’ more for it, Gypo. Just go to sleep.”

But somehow this evening, and for the first time in my life, Merkel’s forgiving eyes and words melted me down.

I thought of two relatively recent similar films (a protagonist enduring terrible guilt after ratting out a comrade) — Yuval Adler and Ali Waked‘s Bethlehem (’13) and Shaka King‘s Judas and the Black Messiah (’21) about FBI informant William O’Neal (Lakeith Stanfield) having inadvertently aided in the murder of Fred Hampton.

Amazon should be ashamed of itself, by the way, for streaming an HD version of The Informer with a horizontally stretched aspect ratio — it should be presented in the original boxy (1.33 or 1.37) but is streaming at 1.85 or 16 x 9 or something close to that.