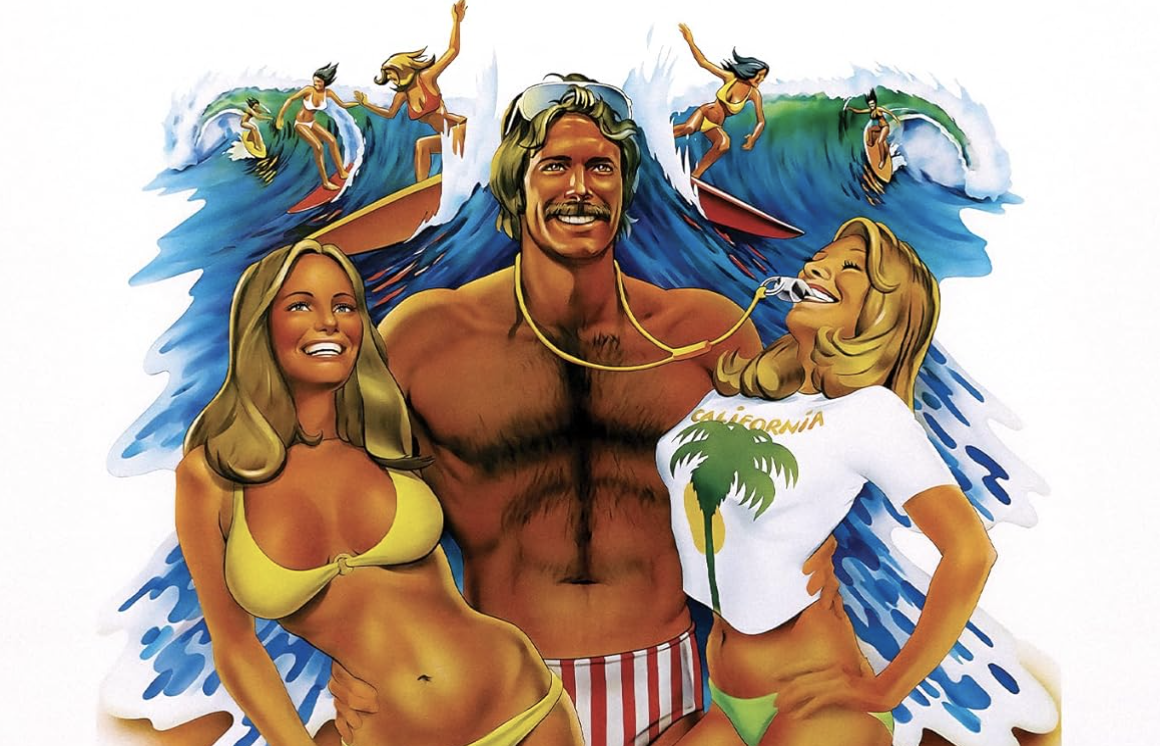

For some reason I’ve decided to re-watch Daniel Petrie and Ron Koslow‘s Lifeguard, which I haven’t seen since the Gerald Ford-Jimmy Carter era…half a century ago!

I love character-driven ’70s films, but this one doesn’t quite get there. It’s fairly compelling or at least interesting in terms of general character tension and low-key social realism (you can really feel the festering ’70s atmosphere), but it leaves you hanging at the end with the slender, dark-haired, good looking protagonist (played by 31 year-old Sam Elliott, who’s currently white-haired and handlebar-stache’d and who sounds like a droopy Deputy Dawg) at some kind of head-scratching, nowhere-man crossroads.

Good character-driven movies have to end with a sense of justice or finality or symmetrical balance…the main characters have to face reality and deal with their decisions in some kind of “okay, you called the shots and now you’re stuck with this” way. Actions have consequences, bruh.

South Bay lifeguard Rick Carlson (Elliott) loves his satisfying beach gig (which allows him to feel like a kind of king mixed with a judicious sheriff) but is bothered by family-and-friendo judgments that he should be manning up professionally and basically making more money and driving a snazzier car.

Rick would kinda like to get married to foxy ex-girlfriend Anne Archer (28 during filming) and vice versa, but she wants him to make more dough and so would he, but “fatten your bank account” isn’t who he is deep down. He tries selling Porsches at a Valley dealership but he hates the routine and quits. He’s reluctant to have sex with the teenaged Kathleen Quinlan (actually 21 during filming) because she’s too young, but he does her anyway. Once, I mean.

So what’s Rick going to do to resolve his situation? Answer: Not much or nothing very different. He’s basically just heading back to the beach. Which leaves you with a feeling of “that’s it?,…aahhh, fuck me.”

That said, Elliott, Quinlan, Archer, Stephen Young (Porsche guy) and Parker Stevenson (a rookie being trained by Elliott) deliver just-right performances. Even with the weak ending and all, Lifeguard is/was Elliott’s best film ever.