Damn Numbers

It was being predicted a couple of weeks ago that the February 27th Oscar telecast will be among the lowest-rated in history, if not the lowest rated. Are we supposed to be concerned? All right, let’s say we are.

In the early to mid 1930s, back when Irving Thalberg had something to say about the way this town was being run, the Oscars were intended as a classy promotion for the studio’s higher-quality films.

The industry was saying to the public, “Enjoy your westerns and your Wallace Beery movies, but keep in mind that every so often the movie industry tries to make films of lasting value, and we’d appreciate your support in these efforts.”

That concept went into the toilet a long time ago, largely due to the interlocking rules of TV ratings and advertising revenues.

People are said to be scared because the Golden Globes awards telecast in mid-January attracted only 16.8 million viewers — 37% less than it enjoyed last year. But this is because it played opposite ABC’s Desperate Housewives, or so goes the rationale.

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

If the Oscar ratings go south, it’ll have nothing to do with Chris Rock being the new host (although I’m sure some industry journos will take a stab at this if the ratings debacle happens). Most of the blame will rest on the shoulders of three Best Picture nominees — Million Dollar Baby , Finding Neverland and Sideways — for not having sold enough tickets, and therefore weakening rooting interest on the part of mainstream viewers.

Ray and The Aviator are the Best Picture nominees that have made reasonably decent coin so far — $74 million and $77 million, respectively. Decent but not humungous.

Actually, Sideways is doing fairly okay for a small film — $15 million earned since the Oscar nominations were announced on 1.25 for a total of close to $48 million. Million Dollar Baby has taken in a post-Oscar-nom $28 million for a $36 million tally. Finding Neverland has received the smallest post-nomination benefit, bringing in almost $7 million for a $36 million gross.

What the doomsayers mean, I suppose, is that none of these films have brought in over $100 million, which implies they aren’t doing as well as they should in the hinterlands. (Most of the money, I’m assuming, has come from blue-state cities, largely because the weakest three haven’t played Bubbaland theatres until fairly recently.)

And so this means…what? That Academy members need to forget about nominating movies and filmmakers that fit their “best” criteria? (Not that they do this with any focus or sincerity now, but that’s another story.) And from here on they need to concentrate on nominating only the movies (and the people who’ve made them) that have sold the most tickets?

This, of course, would be tantamount to turning the Oscars into the People’s Choice Awards, but everything’s swirling in a downward direction anyway so why not?

“The Aviator might have a chance at breaking $100 million because of all of its nominations,” Box Office Mojo’s Brandon Gray told USA Today‘s Scott Bowles in a recent piece. “But that’s a long shot. The other movies are middling performers that people don’t care about.”

People don’t care about seeing Million Dollar Baby or Sideways? What kind of dead-to-the-world, potato-chip-munching attitude is that?

On the other hand, I half sympathize with people saying “naahh, later” to Finding Neverland. It’s a decent heartfelt little film, but Kate Winslet and her coughing…oy. And it’s hard to suppress the urge to strangle Johnny Depp and be rid of his burry Scottish accent for good.

I don’t know why I’ve even getting into this. It’s appalling that people are saying that the Oscar show, or the concept of the Oscars, needs to adapt to the aesthetic vistas of a nation of rurals who wear flip-flops and don’t read Anthony Lane (much less anything hardbound) and spend too much time on the couch.

Isn’t the Oscar-choosing process polluted enough? I guess not.

My son Jett, 16, doesn’t respect the Oscars, and is saying he doesn’t care that much about watching the show this year. A lot of people have written in and said the same thing. This probably means that the show needs to change, get loose, get a new spikey haircut…but in what fashion or direction?

Or is it the movies themselves that aren’t working, or are missing, to an increasing degree, something fundamental?

A friend explains the basic problem as follows: The studios and the “dependents” aren’t making movies for the Big Middle anymore, and the backwash of this policy has been affecting interest in the Oscar awards. And it’s only going to get worse.

The studios are primarily in the super-budgeted, theme-park, Brad Pitt, make-sure-it-plays-in-Germany-and-Croatia business. Some good big-studio pics are getting made here and there, but mostly we’re getting C-level projects at A-level budgets.

(There are only two possible big-studio Oscar contenders opening between late April and Labor Day: Ron Howard’s Cinderella Man and Cameron Crowe’s Elizabethtown.)

And the smaller outfits, my friend said, are mostly about making or acquiring films aimed at better educated blue-state audiences (i.e., Sideways).

I don’t like that people have been labeling Alexander Payne’s film this way. It’s not about a couple of celestial physics instructors, but about the kind of guys everyone knows or at least rubs up against. But when you keep hearing the same things over and over, it’s hard to keep arguing.

A friend who loves Sideways took a Manhattan-raised ex-boyfriend to see it last week and he started seriously complaining about it about 45 minutes in. “I can’t take this…it’s all about drinking,” he said. He insisted on leaving. They went across the lobby and saw Hide and Seek instead.

Obviously this guy’s a lowbrow (with a past alcohol problem, I’m told, which explains his reaction) but avoidance scenarios like this have probably happened with others.

For some reason, and despite being called the Best Picture of the Year by almost every critic in the country, Sideways is doing only pretty well. It hasn’t really caught on, and I keep sensing that people are smelling something they don’t like about it. This sounds cruel, but they seem to have some kind of problem with movies starring (or are largely about or cuddle up to) balding, bearded, whiny-voiced pudgeballs.

I just can’t accept that would-be moviegoers are asking each other what they want to see on a Friday night, with one saying “what about Million Dollar Baby?” and the other saying “naaah.” I refuse to live in a world that shuttered.

And yet I think people should at least go to The Aviator, despite the several irritations. (DiCaprio is brilliant, despite his not being quite the right guy to play Howard Hughes, and it is, you know, a Scorsese film.)

It’s ironic, of course, that the one Best Picture nominee that people haven’t had to talk themselves (or their dates) into seeing, is arguably the weakest candidate. And I loved watching it last fall, and I’ll watch it again this week on DVD. What’d I say?

Smart Bomb

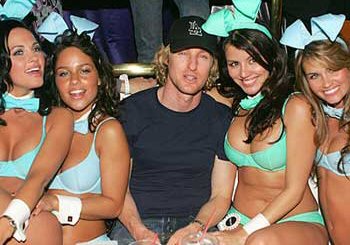

My natural tendency is to side with a critic or journalist when there’s some kind of scuffle, but I thought the writing that went into Owen Wilson’s hammering of New Yorker critic David Denby for his slice-and-dice of Wilson’s longtime homie and costar Ben Stiller was pretty tasty.

I know, I know…I should have run with this last Monday or Tuesday.

At the very least, Wilson’s witty tirade makes for a more elevated contretemps than the one that went down between actor Rob Schneider and L.A. Times columnist Patrick Goldstein, which was largely about Schneider’s attempt to trash Goldstein’s rep by pointing out he’s never won any journalism awards, whatever that infers.

Here’s Wilson’s thing:

“I read David Denby’s piece on Ben Stiller with great interest (“The Current Cinema,” January 24th & 31st). Not because it was good or fair toward my friend but exactly because it wasn’t,” he began.

“I’ve acted in two hundred and thirty-seven buddy movies and, with that experience, I’ve developed an almost preternatural feel for the beats that any good buddy movie must have. And maybe the most crucial audience-rewarding beat is where one buddy comes to the aid of the other guy to help defeat a villain.

“Or bully. Or jerk. Someone the audience can really root against. And in Denby I realized excitedly that I had hit the trifecta. How could an audience not be dying for a real `Billy Jack’ moment of reckoning for Denby after her dismisses or diminishes or just plain insults practically everything Stiller had ever worked on?

“And not letting it rest there, in true bully fashion Denby moves on to take some shots at the way Ben looks and even his Jewishness, describing him as the `latest, and crudest, version of the urban Jewish male on the make.’ The audience is practically howling for blood! I really wish I could deliver for them–but that’s Jackie Chan’s role.”

Here’s the link to Denby’s Stiller piece.

Downfall

There’s a nicely written, highly persuasive piece by Louis Menand in this week’s New Yorker called “Gross Points.”

Here’s Menand’s entire piece and here are some excerpts:

“The people who make the popcorn basically know what they’re doing. The people who make the movies basically don’t, at least not until the product is out there, and then it’s too late.

“The history of Hollywood is a comic routine of bad guesses, unintended outcomes, and pure luck. Half of the failures were well-intentioned, and half of the successes were, by ordinary standards of fairness and decency, undeserved. People do get rich making movies; more often than not, they’re the wrong people. That’s why moviemaking is so much fun to read about. Unless, of course, it’s your money.

“The cinema, like the novel, is always dying. The movies were killed by sequels; they were killed by conglomerates; they were killed by special effects. Heaven’s Gate was the end; Star Wars was the end; Jaws did it. It was the ratings system, profit participation, television, the blacklist, the collapse of the studio system, the Production Code. The movies should never have gone to color; they should never have gone to sound. The movies have been declared dead so many times that it is almost surprising that they were born…”

Of course, ‘death,’ in this context, does not mean ‘extinction.’ What it means depends on the speaker.

“David Thomson’s The Whole Equation: A History of Hollywood (Knopf; $27.95) is a coroner’s report. The title is misleading. The book gives roughly two hundred and ninety pages to the first fifty years of Hollywood and about eighty pages to the last fifty, and the true scope of its interest is even narrower.

“Thomson thinks that Hollywood had only two phases of first-class product: from 1927 to 1948, The Jazz Singer to the Paramount decision (the Supreme Court case that broke the studio system by forcing the studios to divest themselves of the theatre chains they owned); and from 1967 to 1975, Bonnie and Clyde to Jaws.

“If you think that our interest in movies has everything to do with our feelings about them, and if you have a tolerance for repetition, digression, first-person indulgence, and general narrative shagginess, then you are not likely to find a more affecting and intellectually absorbing book on film as a popular art. Thomson’s subject is not, strictly speaking, the history of the movies; its subject is the history of caring about the movies. That calls for something more than just the facts.

“Giants like [Independence Day, Godzilla, Pearl Harbor and the two Matrix sequels] continue to stalk through the multiplexes, shaking gold from the heavens with their thunderous, THX Certified footsteps; but inside their high-definition, digitized craniums their tiny brains are dead.

“[This] wouldn’t matter so much now if the industry didn’t care. But the industry does care. The people who make movies need to be able to take themselves more seriously than the people who make popcorn do. The situation would be simpler if everyone was certain that the movies making money today have no more creative integrity or cultural significance than a beer commercial. But no one is certain. People fear that they’ve lost the key to the distinction.

“Most autopsies of the cinema tend to be `it all started to go wrong when…’ narratives. They’re appealing in the same way those `wise old person who knows the secret’ stories that turn up in so many fantasy-adventure movies today are appealing, and they have the same shortcoming, which is that in life there never is just one secret, and there never is just one cause.

“In the case of a collaborative, semi-regulated, high-cap, worldwide, mass-market entertainment like a Hollywood movie, identifying causes is like predicting next year’s weather. A butterfly flutters its wings in Culver City, and a decade later you get The Terminator.

“One of the merits of The Whole Equation is that it avoids isolating a cause of death. It maintains a kind of analytic deep focus; it tries to take in everything. Thomson thinks that some of the explanation for what happened to the movies has to do with the movies and the people who make them, but some of it has to do with the audience. `It’s not so much that movies are dead,’ he suggests at one point, `as that history has already passed them by.’

“Today, there are thirty-six thousand screens in the United States and two hundred and ninety-five million people, and weekly attendance is twenty-five million.

“And what is the main cinematic experience? The tickets, including the surcharge for ordering online, cost about the same as the monthly cable bill. A medium popcorn is five dollars; the smallest bottled water is three. The show begins with twenty minutes of commercials, spots promoting the theatre chain, and previews for movies coming out next Memorial Day, sometimes a year from next Memorial Day.

“The feature includes any combination of the following: wizards; slinky women of few words; men of few words who can expertly drive anything, spectacularly wreck anything, and leap safely from the top of anything; characters from comic books, sixth-grade world-history textbooks, or ‘Bulfinch’s Mythology’; explosions; phenomena unknown to science; a computer whiz with attitude; a brand-name soft drink, running shoe, or candy bar; an incarnation of pure evil; more explosions; and the voice of Robin Williams.

“The movie feels about twenty minutes too long; the reviews are mixed; nobody really loves it; and it grosses several hundred million dollars.

“The blockbuster is a Hollywood tradition, but blockbuster dependence is a disease. It sucks the talent and the resources out of every other part of the industry. A contemporary blockbuster could almost be defined as a movie in which production value is in inverse proportion to content.

“Troy is a comic strip, but what a lavish, loving, costly comic strip it is. The talent, knowledge, and ingenuity required to make just one of the battle scenes in that film, or one mindless James Bond chase sequence, interchangeable in memory with almost any other Bond chase sequence, would drain the resources of many universities.

“But why doesn’t anyone put more than two seconds’ thought into the story? The attention to detail in movies today is fantastic. There is nothing cheap or tacky about Hollywood’s product, but there is something empty. Or maybe the emptiness is in us.”

Forecast

David Poland ran a list this morning of some ’05 films he thinks will be Oscar nominated as of 1.25.06. I agree with all of them except two.

Forget about Columbia’s Memoirs of a Geisha. I realize how lowbrow this sounds, but any movie title with the word “geisha” is out, as it obviously portends something excessively delicate and (let’s be honest) probably dreary.

And forget Universal’s King Kong — double-triple-quadruple forget it. A remake of a classic ape movie with Andy Serkis as the ape can’t be Oscar material, and no rational person out there expects it to be…especially under the hand of Peter Jackson.

Tribute