Sandstorm-strength grain is a technological blight that classic-era filmmakers had no choice but to work with as best they could. Bring the great directors back to life — Wilder, Lubitsch, Fleming, Capra, Hawks, Ford, Griffith, Keaton, Hitchcock — and they would all say, “Yes, naturally, obviously, of course…ask Lowry Digital‘s John Lowry to do what he can to tastefully take down the grain levels in our films! Because we want our films to be seen, and we never liked that damn grain gravel to begin with.”

Take no notice of the present-day monks who say that grain is beautiful, vital, essential. It is a visual hindrance to be fought tooth and nail down to the last dying breath. Because if they have their way the grain monks, who care only about the perpetration of their own dweeby world in the Abbey of St. Martin in rural France, will strongly discourage today’s younger generations of film lovers (as well as generations to come) from even thinking about watching the great classics.

I suspect that younger film lovers are as averse to Arabian grainstorm images as I’ve been all my life to silent films. I’m ashamed to admit that I’m always putting off watching this or that great silent classic on DVD because of a lifelong impatience with lack of dialogue (among other tinny ’20s elements that tend to get in the way for a TV generation guy like myself, such as the exaggerated acting styles and too-often static cinematography). I watch these films but grudgingly. I’m not proud of this, mind, but it’s a fact. And I’m probably more receptive to movie lore than your average non-pro film buff.

The younger folks of today (i.e., 25 and under) regard movies made before the ’90s as old, and films from the big-studio era as Paleozoic. Silent films are almost totally out the window for my two sons (who are 20 and 19), but to foster at least some degree of reverence and affection for the 1930-to-1970 era, the old films have to be semi-watchable in a cleaned-up way, and by this I mean aesthetically free of any rickety aroma.

That doesn’t mean they should be degraded down to a plastic visual realm akin to digital video games, as some irrational monks on this site have suggested. It means de-graining them with respect, taste and affection. But it also means removing the damn sand already, or as much as possible without violating the core intentions of the filmmakers.

These guys didn’t love grain. Their films were covered with the stuff — hello? – because they had no choice.

Grain reduction can be done correctly, reverently. Look at the Blu-ray Pinocchio (which Some Came Running’s Glenn Kenny has just written about), or the Blu-ray Casablanca. (I’ve never seen the Blu-ray of Michael Curtiz‘s Robin Hood — how is it?)

And that means one thing — elevating John Lowry and his grain-reduction technology to a position equal to that of Jonas Salk and his 1950s polio vaccine. But before this happens there can be no more tolerance of the monk aesthetic. These people are equivalent to the ultra-right-wing Hebrew rabbinicals who’ve been the most persistent opponents of accord with the Palestinians. Due respect, but people on my side of the issue need to get all Torquemada on their ass. The more the monks get to call the shots about transferring old films to high-def formats, the worse things will be as far as the future of film culture will be. Because they are standing in the way of the church taking in new members and making new converts.

The very survival of the culture of classic film lovers over the next ten to twenty years and beyond is at stake. These well-meaning purists are doing everything in their power to preserve the celluloid grain reality of the past (okay, for the “right” reasons, granted) but are, I suspect, dimming enthusiasm among GenY and GenD viewers for pre-1970 Hollywood classics in the bargain.

This issue has only come to the fore with Blu-ray technology because now you can see the grain much more clearly. I popped in an eight-year-old Dr. Strangelove DVD the other day and was shocked at how much grainier it looks on my 42-inch Panasonic plasma than on my six year-old 36″ Sony analog flat-screen.

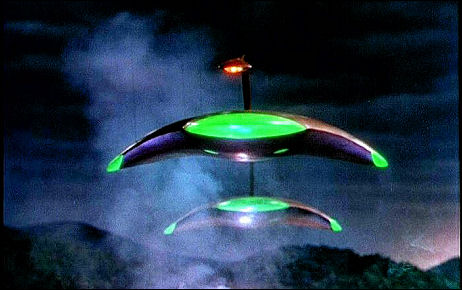

High-def, in short, is exposing the granular reality of how these films look more than ever before. In the same way that the most recent digital mastering of George Pal‘s War of the Worlds (’53) exposed the wires holding up the Martian space ships. Only an oddball like DVD Talk‘s Glenn Erickson would say that seeing the wires is an okay thing. (“There was no CG wire removal in 1953,” Erickson wrote in ’05, “and it would be detrimental revisionism to change the picture now [so] learn to live with it.”) The wires obviously weren’t intended to be seen, and the obvious remedy is to go into the current transfer and digitally remove them — simple. That’s all I’m talking about in general. Remove the stuff from older films that distracts the viewer from the dream state that movies are supposed to lull you into. Because grain is the worst waker-upper of all.

In a figurative way the monks already have already been excommunicated or I wouldn’t be referring to them as monks, but they clearly hold sway among the current generation of film preservationists and restoration experts (Robert Harris, Grover Crisp, Scott McQueen , etc.) and at the Criterion Co., which is pretty much mad monk central these days, to go by their work on the Blu-ray of The Third Man.