For a gripping account of the ghastly 1955 murder of 14 year-old Emmett Till in Money, Mississippi, and the despicable perversion of justice that followed, Stanley Nelson and Marcia A. Smith‘s The Murder of Emmett Till, a 2003 American Experience doc, is your best bet.

Having just seen and been moved by Chinonye Chukwu‘s Till (UA Releasing, 10.14), I’m actually planning to rewatch the PBS doc.

Partly (and I don’t mean this in a naysaying sense) because Till is not a tightly focused, chapter-and-verse procedural about the tragic facts, and that’s what I, a shameless just-the-facts type, more or less wanted the whole time.

Which is not to say Till is a problem film — it’s not. It’s just that it’s strictly focused on the agonizing ordeal of Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley (Danielle Deadwyler), and about the dignity and resolve that this half-broken woman summoned in order to bring about a form of justice for her son.

Not legal justice, of course — not in the Jim Crow south of the mid ’50s. But the justice of history and all the facts being known.

Co-written by Michael Reilly, Keith Beauchamp and Chukwu, Till recounts the basics of Emmett’s Chicago life (sharing a home with Mamie, his colorful personality and natty clothing) before his visit to Money in late August of ’55, and how his expression of hormonal arousal (a wolf whistle) directed at Carolyn Bryant, a married 21 year-old storekeep, led to his killing by her husband and half-brother because he’d violated a sexual racial barrier.

The heart of the film is how Mamie dealt with this horrible occurence, and particularly her decision to reveal her son’s mutilated, bloated, bashed-in head to the world by opening the casket lid during his Chicago funeral. This was followed by her Mississippi testimony at the trial of his killers.

Till’s murder is aurally suggested but mercifully not shown.

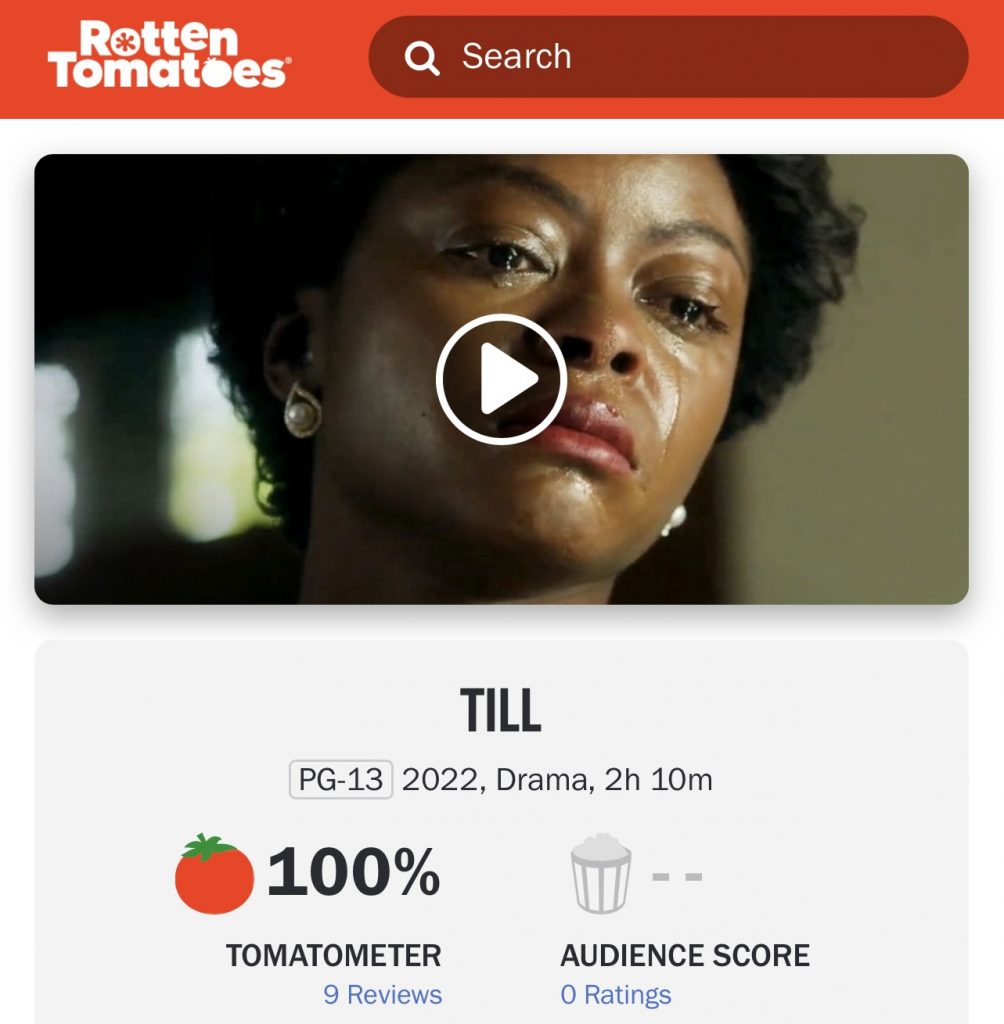

Till is sad and penetrating and well acted up and down, but award-season-wise it’s mainly an acting showcase vehicle for the gifted Deadwyler, who will obviously be nominated for a Best Actress Oscar. She channels three simultaneous currents — devotion, devastation, steel.

Till is deeply appalling and sadly factual. But it’s not a satisfying story because the actual story itself was unsatisfying. Not only were the bad guys not convicted but they even pocketed a fat fee when they admitted to killing Emmett in a Look magazine article.

If you want the kind of emotional satisfaction that results when the bad guys pay for their foul deeds, re-watch the fictional Mississippi Burning. But if you want to submit to a wowser, soul-deep lead performance, see Till.