Tom DiCillo‘s Delirious (Peace Arch, 8.15) is a relationship story about a gauche, low-level Manhattan paparazzi (Steve Buscemi) and a scruffy wannabe actor (Michael Pitt ) who talks the photographer into giving him a gig as his unpaid assistant. Buscemi shows Pitt the ropes of Manhattan celebrity-stalking, then a pretty but insecure young singer (Alison Lohman) takes a shine to Pitt and before you know it he’s working on a TV show and being snapped himself and Buscemi is the odd man out with his nose against the glass.

You can spot the references right off the top — a little Midnight Cowboy, a little Star is Born, etc.

The reactions to Delirious so far are running 100% positive on Rotten Tomatoes. One of the better written raves is by New Yorker critic David Denby, who calls it “a strong, bitter movie [about] a brutal and unstable process” — i.e., the icky, often ugly relationship of mutual loathing and reciprocity between celebrities and papar- azzi. He also called it “exhilarating in a way that only hard-won knowledge of the world can be.”

I didn’t feel exhilaration at all. I was okay with it by way of a certain respect, a certain recognition, a certain liking.

Delirious is a good in-and-out film (sometimes hilarious, sometimes just okay, sometimes sad and tender) but deep down it seems to be driven by feelings of outwardly-directed loathing on DiCillo’s part, for paparazzi riff-raff as well as fringe losers in general. I’m not saying this is absolutely the case, but it feels this way to me. This is my explanation, in any event, as to why the film feels seems less particular and perceptive than it ought to be.

Buscemi’s character is the main problem. All through the film he’s an immature jerk and an undisciplined id monster — screaming at doormen, acting rash and desperate and often unclassy, making stupid social blunders. In a racket as tough as celebrity photography, even the scummiest bottom-feeder needs to act like someone much better than he or she is when it comes to dealing with other profes- sionals — you need to put on a wise, cultivated and diplomatic Henry Kissinger face.

I know a little bit about getting into hot parties and dealing with door guys and publicists, and there’s just no way that Buscemi’s character could make any headway in the real world. I admit I don’t personally know any paparazzi so Buscemi’s guy may be an accurate representation, but he’s way too much of a creep for my tastes.

A guy in his late 40s who gets all upset because his parents don’t respect his work is, to my mind, a child, and who has time for that? I didn’t buy Buscemi’s home-visit scene either — what parent blatantly tells an offspring that what they’re up to professionally is worthless? Invited to a small private party with Elvis Costello in attendance, Buscemi’s guy just pulls out his camera and starts snapping away, which naturally pisses off Costello to no end. Even animal-level paparazzi would know not to play it this way. Celebrity-world operators without charm or finesse are pathetic.

If DiCillo respected guys like Buscemi a bit more he might have delved more in the minutae of who they really are and what their lives are actually like, and he would have created a slightly more rounded and particular portrait. Or at least one that wouldn’t get this kind of reaction from the likes of me.

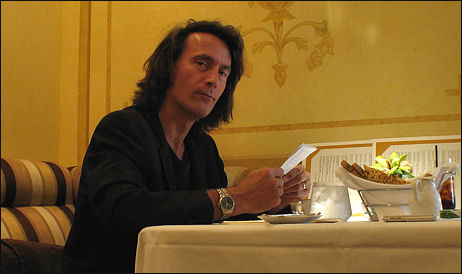

Why, then, did I sit down with DiCillo last week and talk with him if I was mixed on the film? Because he’s a good guy to shoot the shit with — frank, confessional — and because I absolutely worship Living in Oblivion, his 1995 film that Denby accurately calls “the best movie made about independent filmmaking.” DiCillo and I spoke eight days ago for about 15 or 20 minutes in the ground-level restaurant at the Four Seasons hotel.