Deep Polanski

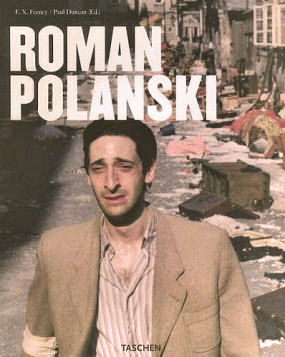

Over the last couple of weeks I’ve been reading “Roman Polanski” (Taschen), an eye-filling and genuinely inspiring review of one of the greatest living filmmakers of our time. It runs 192 pages, and I wouldn’t have minded an extra 100 pages or so. I have no problem with calling it the most insightful, alluring and fetchingly phrased book about Polanski ever.

The photos, selected by editor Paul Duncan, are exceptional but F.X. Feeney’s smoothly written 30,000-word essay is the soul of it. The book is a peach and a picnic for lovers of “Repulsion”, “Knife in the Water”, “Rosemary’s Baby”, “China- town”, “The Pianist”, “Macbeth”. It even made me want to return to “Frantic”, which I bought into because I found it impossible to believe that Harrison Ford would marry Betty Buckley.

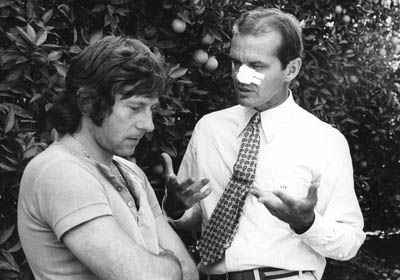

Roman Polanski (l.) and Jack Nicholson during the making of Chinatown (1974)

One look at “Repulsion”, which I first saw in my early 20s, and it was clear Polanski knew how to sock it to you but good. That rotting rabbit on the plate, the bleeding cuticle of that old woman in the beauty salon, the man briefly reflected in the closet-door mirror, that loudly ticking clock, the cracking walls — Polanski was a guy who knew from nightmares and had a knack for conveying creepiness and perversity in a way that anyone could feel.

The idea you always get from any Polanksi film is that life is not to be trusted, unsafe…teeming with predators. Feeney’s copy notes that “the ghostly truth [behind his films] is that Polanski was orphaned by the Nazis and wandered Poland alone from ages 9 to 13. In each of his films, the omniscient viewpoint feels ‘childlike’ in the least innocent sense: we listen and watch…wary of what’s been hidden or is being planned in secret,…one’s survival (even within the playful confines of a fantasy) depends on not missing so much as one detail.”

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

I’ve been talking to F.X. about doing an interview about the Polanski book since mid June. Last week I hit upon the idea of simply writing out a few e-mailed questions and having F.X. write back. His replies came in yesterday and here they are:

HE: How long did it take you to research, write, and then re-write everything? How many words? When did you do the work?

Feeney: I worked from October 2003, to early May 2004. Mind you, I had been researching it since the late `60s and early `70s, when I was in my late teens. Polanski was a very early hero of mine. I have always felt at home in his films. There was never any need to ‘interpret’ his movies, as with other greats.

“The only way I could make sense of 2001: A Space Odyssey when I first saw it was to try and understand the ‘meaning’ of the monolith. Polanski was immediately involving, by contrast. If you’ve ever felt scared while you’re alone in a house, Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby make instant sense. Any kid, any grownup, can watch and be perversely tickled by firsthand knowledge of what those poor heroines are feeling.

“My hands-on research began as I tramped around Poland in late November and early December of 2003. I visited the house where Polanski lived in Krakow, prior to the Nazi invasion. A local guide — a wonderful character who calls himself ‘Bob of Bobtours dot com’ — drove me to Wysoka, in the Tatras mountains south of Krakow, where Polanski hid out after escaping the ghetto at age 9.

“A 90 year-old camp survivor living up in those hills remembered the family Polanski boarded with, and directed us precisely to the spot where their hut once stood. (‘Three bus stops past the church, to where a long road curves up to the right.’) A photo I took of that place is in the book — along with another I took of the ‘half lion, half dragon’ Polanski remembers over the door to the house where he spent his few happy times as a kid.

“The following week I went to CAMERIMAGE, a magnificent, intimate, world-class film festival devoted to honoring cinematographers, and held each year in Lodz, Poland. Polanski attended the film school at Lodz — pronounced ‘Woodge,’ and fondly nicknamed “Hollywoodge” by partisans of the festival.

Catherine Denueve in Repulsion (1965)

“There, in addition to hobnobbing with David Lynch, Peter Weir, James Ivory, Christopher Doyle and an army of great cameramen and young filmmakers, I ran into a wealth of Polanski’s old schoolmates, and was even given a tour of the film school, which is still thriving. “Polanski always sat there, on the seventh step,” the rector told me as we climbed the wide staircase to the screening room, where the students used to hang out and socialize by the hour.

HE: How did you speak with Polanski? (Over the phone, I presume.) How many conversations? How long did the interview process take?

Feeney: “There were no conversations with Polanski. When I first reached out to him, through a mutual friend — film director Hubert Cornfield, now deceased — Polanski’s response was courteous but absolute: ‘I hope never to be interviewed, ever again.’

“Truth is, Polanski has dealt with everything in print over the past 40 years, be it the Nazis’ murder of his mother, the Manson gang’s massacre of Sharon Tate and his unborn son, even the incident of ‘unlawful sex with a minor’ (which is the actual wording of the crime for which he pled guilty — not statutory rape), and the question of whether or not he’s coming back to America — he’s dealt with all of it, exhaustively, in print and on TV, again and again.

“A fellow Polanski scholar, Paul Cronin — editor of ‘Roman Polanski: Interviews’ — shared an indispensible bulk from his archive. But above all there is Polanski’s own 1984 autobiography, which is blisteringly honest. I decided to fuse these countless fragments into a coherent mosaic while focusing primarily on the films.

Polanski’s wife and actress Emmanuelle Seigner with Polanski two or three years ago

“Polanski did cooperate very generously in terms of providing access to the rare graphic images at his office that my editor Paul Duncan gathered for his superb layouts. Polanski never intervened, though he did review the text for factual inaccuracies. In my original draft I had written that Wysoka is 35 kilometers south of Krakow — he changed that to 40. He adjusted one or two other things of that nature. Otherwise, his stance was a respectful ‘no comment,’ good or bad.”

HE: What film is he proudest of at this stage? My guess is The Pianist, but maybe it’s Knife in the Water or Cul de Sac.

Feeney: “Cul de Sac is his favorite, of record — everything that is most pure and original in himself is in that film, although it was hell to make. (Uncooperative weather, bedbugs at night, moody actors.) His two favorite working experiences were Chinatown and The Pianist — in each case, he enjoyed the unwavering support of his backers, cast and crew.”

HE: What is your favorite Polanski film personally? Which of his films do you think is the greatest? And why?

Feeney: “This is like asking me my favorite Beatles song. (Actually, that would be ‘You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away’ — but do we have to sacrifice all the rest?)

John Huston, Jack Nicholson in Chinatown

HE: Will Polanski ever return to this country?

Feeney: “The great misconception I try to correct in the book is the question of why he’s in exile. Several times, lately, in a number of venues, I’ve come across erroneous newspaper accounts which say ‘Polanski fled the US to escape arrest.’ No — he pleaded guilty, took full responsibility, even did prison time and stood ready to pay a hefty fine. Unfortunately Judge Laurence J. Rittenband reacted badly to the overheated media coverage. The day after Polanski was released from Chino [state prison], Rittenband reneged on the careful deal worked out with the prosecutors and arbitrarily threatened Polanski with further and unlimited jail-time. The judge’s freakout became contageous and Polanski boarded the next jet out of Dodge. (See pages 109 and 111 of my book.)

“As for his present exile, and his chances of returning: Remember The Exterminating Angel, the Bunuel classic in which dozens of wealthy people are trapped at a party for 40 days and 40 nights (eventually resorting to cannibalism), all because nobody wants to be thought rude by being the first to leave? That’s Polanski’s position. He pleaded guilty, he did time, he made amends — through civil courts, he settled with the young woman in the late 1980s / early 1990s. The way is technically clear to an amnesty, but nobody in power wants to be the first one to let him off the hook.

HE: My favorite Polanski scenes are in Repulsion. The loud ticking clock as Catherine Deneueve lies in bed, terrified that an intruder will come into her bedroom, etc. And the arms and hands shooting out from the walls and grabbing her. What are your favorites?

Feeney: “I’m with you in loving Repulsion, through and through. As for Cul de Sac, I would call your attention to a few things — particularly the long magical interlude on the beach at daybreak, all done in one breathtakingly sustained complex master shot. There, Donald Pleasance, Lionel Stander and Francois Dorleac — Catherine Deneueve’s elder sister, dead in a car crash later in 1966 — get along peaceably for a change. It’s subtle, but the rest of the movie’s emotional power is energized by this little truce.

Mia Farrow in Rosemary’s Baby

“In Chinatown, pick any scene. My favorites tend to involve John Huston — but as Robert Towne points out, check out and savor any scene in where the characters (and ourselves) are obliged to wait. Take the moment when Jake is rudely forced to wait all day in a Water & Power honcho’s outer office. He persists in waiting — to the great irritation of the secretary. The same goes, more famously, for the little showdown through gritted teeth with the clerk at the hall of records. Who among contemporary directors would have the bold audience sense to try such scenes, much less pull them off? Paul Thomas Anderson comes to mind, but otherwise? Almost no one.

“Polanski’s last five films are all great, in my opinion. Bitter Moon (1992) is a sexy wonder, Death and the Maiden (1995) a magnificent thematic follow-up to Chinatown particularly as articulated by Noah Cross (Huston) to Jake Gittes, when he says: “Most people never have to face the fact that, under the right circumstances, they’re capable of anything.” Ben Kingsley, Sigourney Weaver and Stuart Wilson give three exceptional performances that demonstrate precisely that horrible truth. The Ninth Gate (1999) is a hoot.

“The Pianist (2002) and Oliver Twist (2005) constitute twin valedictories — the former recreates the historic reality of Polanski’s childhood with a vital fidelity, and the latter catches the inner reality of his childhood — at large in a hostile universe, but protected by an indestructible optimism.”

Wells addendum: I have one beef with the book, which is the cover photo — a shot of a tearful, devastated Adrien Brody in The Pianist walking down a littered street. This is not Polanski to me — a man full of grief and pain. Polanski, to me, is the crafty jackal, the brilliant manipulator, the pervy purveyor of the sinister. Polanski is not about boo-hoo but heh-heh. He’s the scared little boy who probably once said to himself, “I’ll escape the clutches of those Nazi bastards, and then I’ll come back when I’m older and make brilliant films and scare the shit out of their sons and daughters and then make them feel ashamed of their parents…hah!”

** Feeney is also the author of Taschen’s forthcoming Michael Mann book, due on 9.5.06.