The spirit of the great Robert Evans has left the earth and risen into the clouds. A fascinating character, a kind of rap artist, a kind of gangsta poet bullshit artist, a magnificent politician, a libertine in his heyday and a solemn mensch (i.e., a guy you could really trust).

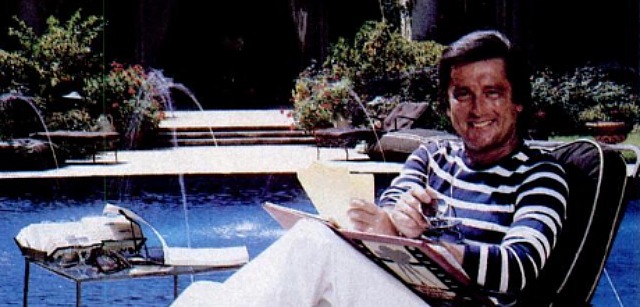

For a period in the mid ’90s (mid ’94 to mid ’96), when I was an occasional visitor at his French chateau home on Woodland Drive, I regarded Evans as an actual near-friend. I was his temporary journalist pally, you see, and there’s nothing like that first blush of a relationship defined and propelled by mutual self-interest, especially when combined with currents of real affection.

There are relatively few human beings in this business, but Evans was one of them.

You’re supposed to know that Evans was a legendary studio exec and producer in the ’60s and ’70s (The Godfather, Chinatown, Marathon Man) who suffered a personal and career crisis in the ’80s only to resurge in the early ’90s as a Paramount-based producer and author (“The Kid Stays in the Picture”) while reinventing himself as a kind of iconic-ironic pop figure as the quintessential old-school Hollywood smoothie.

From my perspective (and, I’m sure, from the perspective of hundreds of others), Evans was a touchingly vulnerable human being. He was very canny and clever and sometimes could be fleetingly moody and mercurial, but he had a soul. He wanted, he needed, he craved, he climbed, he attained…he carved his own name in stone.

The Evans legend is forever. It sprawls across the Los Angeles skies and sprinkles down like rain. Late 20th Century Hollywood lore is inseparable from the Evans saga — the glorious ups of the late ’60s and ’70s and downs of the mid ’80s, the hits and flops and the constant dreaming, striving, scheming, reminiscing and sharing of that gentle, wistful Evans philosophy.

He was an authentic Republican, which is to say a believer in the endeavors of small businessmen and the government not making it too tough on them.

Rundown of Paramount studio chief and hotshot producer output during the Hollywood glory days of the late ’60s, ’70s and early ’80s — (at Paramount) Rosemary’s Baby, Love Story, Harold and Maude, The Godfather, Serpico, Save The Tiger, The Conversation; (as stand-alone producer) Chinatown, Marathon Man, Black Sunday, Urban Cowboy, Popeye, The Cotton Club, Sliver, Jade, The Phantom, etc.

Not to mention “The Kid Stays in the Picture” (best-selling book and documentary) and, of course, Kid Notorious. Not to mention Dustin Hoffman‘s Evans-based producer character in Wag the Dog.

And you absolutely must read Michael Daly‘s “The Making of The Cotton Club,” a New York magazine article that ran 22 pages including art (pgs. 41 thru 63) and hit the stands on 5.7.84.

I’ve posted the following recollection three or four times but what the hell…

Paul Verhoeven‘s Showgirls opened and crashed in September of ’95. I’d attended a press screening a week or two before and figured that was enough, but I manfully sat through it a second time a couple of weeks after it opened, or sometime in early October. Reason? Jack Nicholson. Yeah, yeah, I’ve told this story twice before but indulge me…

I was having dinner that night with Robert Evans in his combination rear bungalow and screening room. It was (and as far as I know still is) a cozy little abode located behind his circle-shaped pool in the backyard of his French chateau-styled place on Woodland Avenue. And the guests that night were Bryan Singer, Chris McQuarrie and Tom DeSanto. And we were all enjoying the great food (served by Alan, Evans’ good-guy butler) and a nice buzz from the excellent wine.

I was Evans’ journalist pally back then. I had written a big piece about Hollywood Republicans earlier that year for Los Angeles magazine, and Evans had been a very helpful source. As a favor I’d been arranging for him to meet some just-emerging GenX filmmakers — Singer, McQuarrie, Owen Wilson (who had come over a week or two earlier), Don Murphy, Jane Hamsher, et. al. — so that maybe, just maybe, he could possibly talk about making films with them down the road.

During the dinner Evans was doing a superb job of not asking Singer, McQuarrie or DeSantos anything about themselves. He spoke only about his past, his lore, his legend. But the vibe, to be sure, was cool and settled and almost serene.

And then out of the blue (or out of the black of night) one of the French doors opened and Nicholson, wearing his trademark shades, popped his head in and announced to everyone without saying hello that “you guys should finish…don’t worry, don’t hurry or anything…we’ll just be in the house…take your time.”

What? Singer, McQuarrie and DeSanto glanced at each other. Did that just happen? Evans told us that Nicholson was there to watch Showgirls, which they’d made arrangements for much earlier. He invited us stay and watch if we wanted. Nobody wanted to sit through Showgirls — the word was out on it — but missing out on the Nicholson schmooze time was, of course, out of the question.

So Jack and two women he was with came back in and the lights went down and we all began watching Showgirls. And we stayed with it for…oh, 40 minutes or so. The spell was broken when Nicholson, who was sitting right under the projection window against the rear wall, stretched his arms and put his two hands right in front of the lamp. The hand-silhouette on top of Elizabeth Berkeley and her grinding costars conveyed his opinion well enough, and suddenly everyone felt at liberty to talk and groan and make cracks and leave for cigarette breaks.

Nicholson and Singer ducked out at one point while the film was running, and I joined them. This is so damn cool, I was telling myself. Moments like this don’t happen often.

There was a little chit-chat after it ended. I recall DeSanto (Apt Pupil, X-Men, X2, Transformers) introducing himself to Nicholson and Jack saying, “And it’s very nice to meet you, Tom.” Gesturing towards the two women who were with him, Nicholson then said to DeSanto, “And I’d like you to meet Cindy and…” Lethal pause. Nicholson had forgotten the other woman’s name. He recovered by grinning and saying with a certain flourish, “Well, these are the girls!” The woman he’d blanked on wore a death-ray look.

We all said goodbye in the foyer of Evans’ main home. Nicholson’s mood was giddy, silly; he was laughing like a teenaged kid who’d just chugged two 16-ounce cans of beer and didn’t care about anything. I was thinking it must be fun to be able to pretty much follow whatever urge or mood comes to mind, knowing that you probably won’t be turned down or told “no” as long as you use a little charm.