Michael Mann’s Ferrari (Neon, 12.25) has turned out to be much better than I expected.

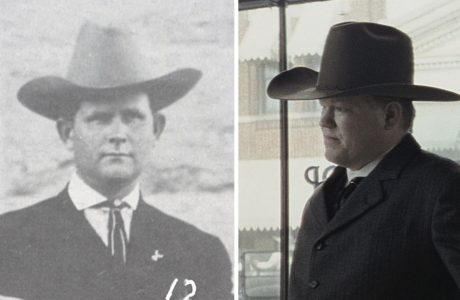

A portrait of aging Italian car magnate Enzo Ferrari struggling to keep his business and family afloat at a highly critical juncture, Ferrari is “better” in terms of recreating the past and a very particular cultural milieu (mid to late ‘50s, northern Italy) and generally radiating a certain textural, visual and emotional verisimilitude that is rather wonderful in its own studious, deep-dish way.

I’ve been reading since last summer that Ferrari is a period racecar drama that doesn’t follow the expected plot contours and certainly not in the fashion of James Mangold’s 2019 Ford vs. Ferrari, another racecar saga which involved the same real-life character (played by Remo Girone) while set in the mid ‘60s, or roughly eight years after Mann’s story.

Ferrari is basically a torrid Italian family drama (Mann meets Luchino Visconti with a splash or two of Douglas Sirk salad dressing) about emotional and financial turmoil afflicting the embattled Ferrari, played by a nattily-dressed, white-haired, slightly paunchy Adam Driver.

Let’s not forget, of course, that two years ago a younger-looking Driver played another head of an elite, world-renowned, family-owned Italian company in Ridley Scott’s House of Gucci.

Let’s be honest — Joe and Jane Popcorn are going to say “this again?”Given the Ferrari-Driver-Gucci overlap, I’m not sure how commercially vigorous Ferrari will turn out to be when it opens in late December. All I know is that despite the vaguely odd-duck, here-we-go-again factor, Ferrari works on its own compelling terms.

Ferrari is about an old man (Ferrari was born in 1898) entwined in a make-or-break struggle to keep his teetering car company afloat while preparing for a climactic, fate-defining cross-country race and while finessing a volatile family situation involving infidelity and conflicted loyalties.

It’s a great time-machine trip, intimate and low-key for the first three quarters but with a serious knockout finale. It’s culturally authentic (you really feel like you’re there) with a sturdy script and several nicely flavored performances…an ensemble piece that pretty much fires on all cylinders.

Ferrari really pays off over the last 35 to 40 minutes, which is almost all racing.

Penelope Cruz’s blistering, tough-as-nails, scorned-wife performance is a guaranteed Best Supporting Actress nomination lock.

Eric Messerschmidt’s cinematography is wonderful — it reminded me of Gordon Willis’s lensing of the first two Godfather films and Part Two in particular.

It’s basically 90 minutes of fractured family drama and a knockout crescendo showing the 1957 Mille Miglia, a decisive, hair-raising event in the fortunes of Ferrari’s precariously financed car company.

The domestic side is basically about Ferrari’s hands being full with Cruz’s angry wife Laura, Ferrari’s mistress Lina Lardi (Shailene Woodley), and loads of financial pressure and numerous wolves at the door.

Mario Andretti: “[Ferrari] just demanded results. But he was a guy who also understood when the cars had shortcomings. He was one that could always appreciate the effort that a driver made, when you were just busting your butt, flat out, flinging the car and all that. He knew and saw that. He was all-in. He had no other interest in life outside of motor racing and all of the intricacies of it. Somewhat misunderstood in many ways because he was so demanding, so tough on everyone, but at the end of the day he was correct. Always correct. And that’s why you had the respect that you had for him.”

I can’t think of a kicker ending so what I’ve written will have to do.