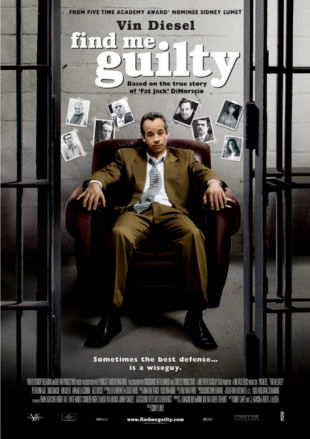

Sidney Lumet‘s Find Me Guilty (Freestyle, 3.17) isn’t just about the rebirth of Lumet’s career (at age 82!) and that of his star, Vin Diesel. It’s also a kind of Damon Runyon-esque joyride — an ethnic-Italian, New York-attitude sociopath movie for those who wink at the bad guys and chuckle when they manage to maneuver their way around the law.

Maybe I’m jaded or I’ve just been Godfather-ed and Soprano-ed into submission, but I bought into most of it and felt pretty much delighted with the care that went into the making of it, and the final ambiguity of it. I was also a bit troubled by it. And yet fascinated.

Vin Diesel as Jackie DiNorscio in Sidney Lumet’s Find Me Guilty (Freestyle, 3.17)

Guilty is unquestionably a marvel of old-fashioned (i.e., ’80s-style) craftsmanship — Lumet’s superb direction, T.J. Mancini and Robert McCrea’s’s finely structured screenplay and skillfully pared-down dialogue, and Diesel’s inescapably charming, sincerely felt performance that puts him back on the road map. (Really — all those mixed memories of XXX and The Pacifier are out the window.)

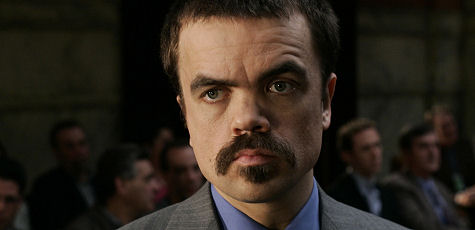

Plus there’s Peter Dinklage and Annabella Sciorra’s superb acting. I genuinely feel that Dinklage, playing a shrewd mob defense attorney with a gift for persuasive oratory, is the first serious contender for Best Supporting Actor for the ’07 Oscar Awards (or at least the ’07 Indie Spirits). And Sciorra almost does here what Robin Wright Penn did last year in Nine Lives, and that’s really saying something.

But there’s some mucky-muck going on. Shot in late ’04, Find Me Guilty has had distribution troubles (it was shopped around and nobody bit) and is being sold the wrong way — the trailer tries to tell you it’s a jaunty mob-guy comedy, a kind of farce, and the music toward the end of the film tries to convey this also, and this feels like a sell-out to the moron trade.

Is everyone listening? Ignore the advertising. The advertising is dishonest.

It’s not without its amusements and gag lines from time to time, but Find Me Guilty is a fairly serious, rooted-in-reality court procedural about wise-guy morality, or the urban mythology about same.

It’s clearly Lumet’s best film since Q & A (1990), and before that Prince of the City (1981). It’s a tight, no-nonsense court drama that’s not about legal maneuvers or discovering evidence or doing right by the system and justice being served, but mob family values.

In a stuffed-manicotti way, Find Me Guilty is as much of a values-based entertain- ment as The Passion of the Christ, My Big Fat Greek Wedding, The Thing About My Folks and Madea’s Family Reunion. I’m serious.

There’s more time spent in a courtoom in this thing than in Lumet’s The Verdict, and for good reason: Find Me Guilty is about the longest-lasting federal criminal prosecution in history. From March ’87 to August ’88, 20 members of the New Jersey-based Lucchese crime family, each represented by his own lawyer, were brought to trial in Newark, New Jersey, on some 76 charges (dope smuggling, gambling, squeezing small businesses…the usual mob stuff).

The feds felt they had an air-tight case, but when the verdict came down…well, let’s not say. But I’ll tell you right now that some people are going to have a problem with this film because of the ending, and especially the tone of it.

Peter Dinklage

The Hollywood Reporter‘s Kirk Honeycutt has already voiced this reservation in his review from last month’s Berlin Film Festival. The community values espoused (or at least given a fair examination) by this film are, from a strictly law-abiding perspective, totally goombah and wholly corrupt. And yet what’s being said here is not without a certain resonance, a certain sincerity of feeling.

These values can be summed up by the words “don’t rat,” “don’t roll” and “family is everything.” I’m no goombah but I sympathize with these sentiments, so I guess that’s part of the territory.

I’m talking about the values of a group of bad guys (i.e., men who live outside the law and occasionally enforce their ethical standards by whacking each other) who ostensibly care for and someitmes “take care of” each other, and about one particular bad guy — Diesel’s Jackie DiNorscio — who stood up for certain things over the course of this trial …loyalty, friendship, togetherness…even if the reality of Italian crime ethics, going by everything I’ve heard, is that everyone rats out everyone else sooner or later and a lot of these guys are just full-out sociopaths, or are viewed this way by the majority. And yet Guilty isn’t an invented story.

This, for me, makes it absolutely fascinating because Lumet, Mancini, McCrea and Diesel are making a moral statement that they obviously have some kind of respect for, and in a serious way. Diesel does his courtroom buffoon routine for entertainment value at regular intervals, but otherwise Find Me Guilty is a fairly sober piece that asks you to grapple with who and what DiNorscio is, and what he’s really saying.

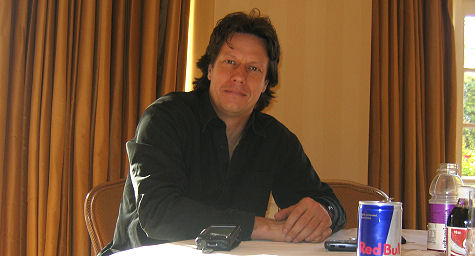

Sidney Lumet, Vin Diesel

The story points and much of the dialogue in Find Me Guilty are taken from court records and based on hard facts, so there’s obviously a kind of imbedded truth in what we’re seeing, but let’s face it — if you were to show this film to Tony Soprano’s crew they would eat it up like baked ziti.

But show this film to a group of straight-arrow law officials from outside of the New Jersey-New York corridor who haven’t seen other ethnically-correct mob movies, and some of them will undoubtedly say, “What the hell is this? Has Hollywood gone totally corrupt?” And yet it happened.

What’s really striking is that Find Me Guilty is pretty much the precise moral opposite of Lumet’s Prince of the City (1981), which is about the emotional agony that a corrupt cop puts himself through when he decides to tell the absolute truth and rat out his equally corrupt cop friends, and ends up despised and lonely and broken.

Find Me Guilty is about a wise guy who refuses to rat out his wise-guy friends, even when most of them shun him and treat him like a leper because of his court behavior, but who nonetheless holds to his own moral ethical course. I’m not going to spill the ending but this is not a movie that ends with the clanking of prison-cell doors a la Goodfellas.

Has there ever been a major-league filmmaker besides Lumet who has made two films about the same culture — the New York-area criminal underworld — with both (a) based on a completely true story about courts and prosecutors and defendants, (b) both grappling with almost the exact same moral-ethical issue, and yet (c) coming to almost the exact opposite conclusions about ratting out your friends?

There are no almost double features these days except at L.A.s Beverly Cinema and New York’s Cinema Village, but Find Me Guilty needs to be paired next year on a double bill with Prince of the City. And when that happens I’m going.

The more I think about this film, which at times feels like a close cousin of William Friedkin’s The Brinks Job, at other times like an earnestly intended moral fable, at at still other times like Prince of the City‘s sociopathic, wise-assed younger brother with a fuck-you-John-Law attitude….the more morally curious and unto-its-own- realm it seems.

I think this is why the distribution community passed — they don’t know what to make of it, and are a little afraid of how the average moviegoer (i.e., those over-30s who will be persuaded to give an old-fashioned Lumet film a shot in the first place) might react.

A dish of cheese ravioli

The hard truth is that Find Me Guilty will most likely tank on its first weekend, but it shouldn’t. It’s a quality thing all the way, it isn’t the least bit boring and is easily among the best of the year so far (alongside Why We Fight, Fateless, Totsi, The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada and Neil Young: Heart of Gold).

There’s no denying that from a craft perspective Find Me Guilty is simply one of the Lumet’s best ever. Mancini and McCrea’s dialogue is sharp, honed, and perfectly seasoned. And his slightly fake-looking rug aside, Diesel is amazing. At times he seems to be just joshing around and more into charming the audience (along with the on-screen jury) that rendering a character, but it gradually seeps in that he’s really playing Jackie DiNorscio and capturing what made him tick and who he really was.

And the supporting actors…fuhgedaboutit. Dinklage (that very cool short guy from The Station Agent) delivers a pitch-perfect performance — an utterly believable incarnation of a fully-rounded hardball lawyer. Sciorra has only one scene with Diesel, in a tiny prison holding room, but the husband-and-wife vibe is dead-on with the old resentments and sexual current getting stronger and stronger — it’s a near-classic scene.

Also excellent are Ron Silver as the presiding judge, Alex Rocco as the viper-like head of the crime family being prosecuted, and Linus Roache as the steely-eyed, go-for-broke prosecutor.

There are fifteen or twenty other actors who are just as good — this film has been perfectly cast in the legendary Lumet-New York street guy tradition by Ellen Chenoweth and Susie Farris. Cheers also for the cinematography by Ron Fortunato, which is beautifully framed and lit all through.

Find Me Guilty is not as good or as interesting as Lumet’s two greatest New York dramas — Dog Day Afternoon and Serpico — because it feels a little too smug at times, a little too invested in trying to charm/amuse the audience with a yea-team finale (using swing music and that Louis Prima tune at the end really undercuts it…a Big Mistake), but it’s certainly in the same moral ballpark, delivers the same high-quality acting and has the same kind of precise and disciplined filmmaking chops that made Prince of the City a great New York drama.

I went in to last night’s screening expecting to see a movie with at least a few problems (given what I’ve heard about the distribution siutation), and I came out almost totally delighted.

Part of the satisfaction of this film is seeing that Lumet still has it together like he did 20 or 30 years ago. He’s been on the “over” list for the last ten years or so, but no longer.

I don’t think it’s a stretch to call Find Me Guilty one of the best films ever made by an 80-something director, which, in this light, puts it alongside John Huston’s Prizzi’s Honor and Robert Bresson’s L’Argent. And that’s good company.

Great Oscar Debates

Nobody disagrees with the notion that Oscar campaigning has become a lot like running for the White House, so why not accept this and stage a special annual series of Academy-sponsored debates at the Academy theatres in Beverly Hills and New York?

Not so much in the manner of the big-candidate debates that (usually) happen in a Presidential election year, but those sometimes stirring speeches that are given at the Republican and Democratic nominating conventions by party leaders, political allies and friends.

Well-known filmmakers, industry figures, esteemed film critics and Academy members could get up in front of a mike and explain why they believe this film or that nominee is especially deserving.

The speakers would offer impressions, career histories, political considerations… whatever. The same views that are routinely shared after screenings and at parties, only with more people listening and with a bit more sobriety all around.

The idea would be to cut through the mental-cobweb impressions, through the party chit-chat and the DVDs and the trade ads and the hate rants.

You can argue that there’s no such thing as a Fog of War element in the various Oscar campaigns and discussions, but I think there is. And it seems to me that specific, impassioned, thought-out reasons to vote for this person or that film would sharpen the focus.

Presidential debates are about candidates trying to tell it straight and cut through impressions created by TV ads and prejudices thrown at the voters. Why shouldn’t the same goal at least be attempted in the Oscar realm? The town obsesses over this darn thing for three or four months out of the year and millions are spent on campaigns, so why the hell not?

The Academy could stage the debates over a two- or three-day weekend at the Academy theatre right after the nominations are announced. It could be a weekend-long festival atmosphere type of thing — food, mingling, film clips, and discussion groups along with the various speakers.

Every nominated person or film would be examined and toasted in some detail, and nominees would be forbidden — only friends, colleagues and publicists could do the pitching. And no negative stuff.

Oscar arguments happen left and right online, of course, but there’s something about live dialogue that cuts through the crap. Every time I get into a friendly dust- up with friends about this or that Oscar contender, I come away with a clearer head.

The whispering campaigns (like the one mounted this year against Paradise Now, or the one that went around a few years back about John Nash, the protagonist- hero of A Beautiful Mind) would almost certainly make less of an impression if the “issues” could be fully aired in a live setting.

People don’t fill out their Academy ballots after thinking things through to the bottom like a Yale mathematician — Oscar favorites are usually emotional gut calls. But perspective and examination can’t hurt the process, and a weekend of Great Oscar Debates would shed light on the short films and the sound-editing nominees and other low-profile contenders.

Imagine Roger Ebert stepping up to the mike and delivering a sharp argument for Crash, or Robert Towne offering an eloquent pitch for Capote , or Annette Bening explaining why she was deeply moved by The Constant Gardener, or David Poland or Tony Angelotti going to bat for Munich…whomever.

Les Girls

A big promotional press event for Bill Condon’s Dreamgirls (DreamWorks, 12.22) happened Monday evening in downtown Los Angeles at the Orpheum theatre and in a big black tent behind it, with rain coming down all over like cats and dogs and everyone coping with the damp overcoats, soaked shoes and matted-down hair.

A ’60s-era musical based on the saga of the Supremes, Dreamgirls has Beyonce Knowles, Jamie Foxx, Eddie Murphy, Jennifer Hudson and Anika Noni Rose in the lead roles. Smells like marquee value, but the Broadway show the film is based upon had its big run in the early to mid ’80s, and so DreamWorks is hoping to prime the potential fan base well in advance of the Christmas ’06 release, hence Monday’s gathering and this official site with basic info, a trailer and behind-the- scenes footage.

The first part of Monday’s soiree happened in the tent. Condon, the director-writer, introduced some of his below-the-line creative team to what looked like a couple of hundred press folk assembled in front of a small stage. He then showed a very brief clip of Foxx and two other guys (projected at a too-wide, not-tall-enough aspect ratio) dancing to a number called “Steppin’ to the Bad Side.”

And then everyone was guided out of the tent, into the rain, across the alley and into the Orpheum and seated in the orchestra section. The film has been shooting in this old-time venue for the past few weeks, with another four or five weeks to go. Three or four cameras were preparing to shoot a song-and-dance scene. A couple of dozen crew members were milling around in the front of the stage area.

As soon as everyone got settled Knowles, Hudson and Rose walked out on stage in sparkly red dresses and began to perform “Step Into the Bad Side” again. The real Supremes wouldn’t have gotten close to a number like this in actuality, but it played appealingly on its own terms.

It ended, everyone applauded and Jamie Foxx came out and said a few words about the film, about the energy of it, about how Murphy (who couldn’t be bothered to show up for the event) was “actually excited” about being in the film, etc.

What I saw and heard felt cool. It seemed to provide a bit more in the way of honest feeling than what Chicago gave up, or so I thought as I was drying off and taking it in.

Producer Craig Zadan told USA Today that “neither Phantom of the Opera, Rent nor The Producers went far enough to turn a stage production into a cinematic experience.”

Rent and The Producers, he said, “were loyal to a fault to Broadway audiences.” With the 10-year-old Rent, “they all looked 35 and were playing 18.”

The trick to a successful transfer to the big screen, Meron says, “is to honor the roots but do the movie.”

Condon, who was Oscar-nominated for his Chicago screenplay, is saying that instead of telling the story through song, like the Broadway show did, he’s added straight dialogue. “It is a realistic medium,” he told USA Today. “And Dreamgirls is a very emotional, somewhat gritty story grounded in reality.”

Knowles is playing Deena Jones, the Diana Ross character. Jennifer Hudson is Effie White, the one who gets shafted as their singing group, the Dreams, gets into the tangle of growing stardom, and who winds up singing, “And I Am Telling You I’m Not Going.” Anika Noni Rose is Lorrell Robinson. Foxx plays their manager, Curtis Taylor, Jr., and Murphy is superstar James “Thunder” Early, whom the Dreams initially do backup singing for.

After the Orpheum performance was over it was back to the tent for drinks and food and more schmoozing time. Beyonce, Jennifer and Anika strolled around and said hello to everyone, but not Foxx.

Condon was hanging and chatting to the end, and talking with me and Pete Hammond and David Poland and DreamWorks marketing exec Terry Press and some others about what surprises, if any, might happen at the Oscars on Sunday. I said I’m hoping for anything along these lines, no matter who I personally want to win, just to make things exciting.

It was still raining like a bitch when I left. It was coming down as if a movie crew had two or three rain machines going at the same time to make sure my character was as soaked as Treat Williams was in that chasing-down-the-poor-junkie scene in Sidney Lumet’s Prince of the City.

Fine Madnesses

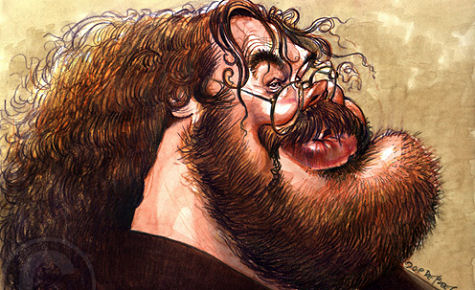

Too much love and success can be a bad thing for movie directors. It can lead to recklessness and ruin. Well, not necessarily. I’m not saying Ang Lee is going to lose his discipline or nice-guyness when and if he wins the Best Director Oscar next Sunday, but there’s at least the threat of this.

Look at the hopelessly over-worshipped Peter Jackson, whose Lord of the Rings trilogy (Oscars, millions, obsequious studio execs) led to the mad-royalty decision to transform King Kong into a three-hour film with a sluggish, borderline deadly 70-minute opening.

Eric von Stroheim (1885 — 1957)

I continue to believe that James Cameron lost his mind (or his nerve, or his will to unscrew tubes and throw paint at the canvas) after the success of Titanic eight years ago. He appears to be on the brink of actually starting a film within the next few months, but the poor guy is still futzing around about which project to do first.

Quentin Tarantino was psychologically done in, I feel, by the huge success of Pulp Fiction in ’94-’95. He stopped hustling, became a party animal, succumbed to some manner of intimidation over the expectations everyone had for his next film, all of which led to the respectable but underwhelming Jackie Brown in ’97.

Michael Cimino surely went mad after the huge success of The Deer Hunter in 1978-79, and from this the gross indulgence that was Heaven’s Gate, his very next film, almost certainly arose.

“At a certain point in their careers — generally right after an enormous popular success — most great movie directors go mad on the potentialities of movies,” Pauline Kael observed in a review of Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1900 when it opened in the States in 1977.

“They leap over their previous work into a dimension beyond the well-crafted dramatic narrative; they make a huge, visionary epic in which they attempt to alter the perceptions of people around the world.”

Today’s directors can’t afford to be as indulgent as the industry allowed them to be in the auteurist playground of the ’70s, and so there’s a lot less flamboyance in the wake of big commercial successes and Oscar crownings.

Peter Jackson

But phenomenal success is still a kind of crippler, I think. It seems to nudge grounded or moderate directors in the direction of fanciful whimsy or big leaps, and if they’re half-mad to begin with they seem to lose it a bit more if they become convinced the world adores them absolutely.

The lesson seems to be that directors can be easily spoiled, like children of a certain age. Keep them on edge, wondering if they’re any good or not, and they’re fine. But beware the pitfalls of love, money, awards, long vacations and relentless kowtowings.

The adulation showered upon Steven Spielberg after Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind almost certainly led to the madhouse atmosphere of 1941 (which some oddball critics, I realize, feel is a work of genius-level choreography).

Orson Welles had a rough time with certain industry heavyweights as a result of making Citizen Kane, only one Oscar award came of it(Best Original Screenplay, which Welles shared with Herman Mankiewicz) and it didn’t make that much money. But he seemed to come away from that film with an arrogant, off-balance attitude that led to his leaving The Magnificent Amberson’s to be edited by RKO editors while he went to South America to shoot a documentary.

James Cameron

Billy Wilder never acted like an indulgent type, but something began to go slightly off in his work after the huge popular successes of Some Like It Hot in 1959 and The Apartment (which also won some Oscars, including Best Picture) in ’60-’61. He wasn’t “over” until Buddy Buddy in ’82, but something about his being a Man of Great Esteem and Accomplishment at the end of the Eisenhower administration didn’t agree with him.

Kael mentioned the madnesses of D.W. Griffith in the wake of Intolerance (1916) and Abel Gance after Napoleon, (1927), and she could have just as easily mentioned the notoriously egoistic behavior of director Eric von Stroheim in the mid 1920s, which led to the excesses of Queen Kelly and his wings being clipped soon after.

Which directors have succumbed to recklnessness (or given a good imitation of same) over the last ten years or so? Please send in names and stories and I’ll update this later tonight.

Losin’ It

I asked for responses yesterday to the “Fine Madnesses” piece, and Francis Coppola in his Apocalyose Now phase was mentioned most often by readers as an example of directorial indulgence. The big runners-up were William Friedkin when he made Sorcerer and the post-Bugsy Barry Levinson.

I disagree about Coppola and Friedkin. Apocalypse was just a brutally hard, financially arduous film to make. If Coppola went through a phase of mad indulgence (“leaping over previous work into a dimension beyond the well-crafted dramatic narrative,” as Pauline Kael once put it), it came with 1982’s One From the Heart. And I’m a huge fan of Sorcerer and see no madness in the way Friedkin shot and cut it.

Here’s a sampling of what came in…

“I’m one of the three people on the planet who liked Barry Levinson’s Toys, but I guess it’s an example of directorial indulgence after Levinson’s success with Bugsy. And of course, Peter Bogdanovich had three hits (The Last Picture Show, What’s Up, Doc?, and Paper Moon) and then three flops (Daisy Miller, At Long Last Love and Nickleodeon).” — Michael Schlesinger

“Steven Soderbergh seems pretty level-headed, but the 2002 combination of Solaris and Full Frontal following the critical praise of Erin Brockovich and Traffic on top of the commercial success of Ocean’s 11 showed some hubris. I don’t think he’s gone around the bend though. And no one can deny that the Wachowski brothers went a little haywire after the success of the first Matrix.” — Chris Lee

“The drops that really interest me are John Hughes and John Landis. Hughes and Landis were some of the first directors whose style and techniques I could easily identify when I was a movie-crazed teen in the 80s, so it was doubly disconcerting when they suddenly crapped out (Landis after The Twilight Zone) or just quit (Hughes).

“There’s also a big ‘personal’ film that bombs. Would a Diner fan who unknowingly watched Toys ever guess it was made by Barry Levinson?” — Neil Harvey

“I’d argue that Peter Jackson crossed the line not after finishing the Lord of the Rings trilogy, but when the first one went over so well. The Fellowship of the Ring is the one with the horse-pills of exposition, but it’s also the shortest and tightest of the series. When it was a huge hit a scored a rack of nominations the pressure was off. The flabby over-confidence of The Return of the King is almost as maddening as it is in King Kong.” — Joe Greenia

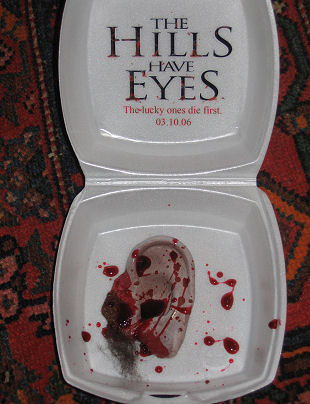

Sequel

Promotional item delivered to my home today (Friday, 2.24), sent by friends at Fox publicity

Spark of Goodness

A little over six months ago I wrote that Gavin Hood’s Tsotsi had become “the big stand-out at the end of the Toronto Film Festival.”

A few weeks later Tsotsi was picked up by Miramax and is playing in theatres starting today (2.24). And it seems safe to say now that it’s the most likely winner of the Best Foreign Language Oscar on March 5th…unless a sufficient number of Academy members take leave of their senses and vote for Joyeux Noel.

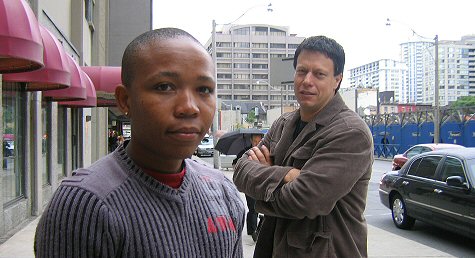

Gavin Hood, director of Tsotsi (Miramax, 2.24), at the Four Seasons hotel — Tuesday, 2.21, 4:20 pm.

Based on a book by South African playwright Athol Fugard and set in a funky Johannesburg shantytown, Tsotsi (pronounced “Sawt-see”) is about a merciless teenage thug (Presley Chweneyagae) who discovers a small spring of compassion in himself when he starts to care for an infant boy he discovers in the back seat of a car he’s stolen.

Tsotsi‘s basic achievement is that it sells the notion in a believably non-sappy way that sparks of kindness exist in even the worst of us.

I knew Tsotsi would probably connect with general audiences when it won the Toronto Film Festival People’s Choice award, which followed a similar win at the Edinburgh Film Festival a month or two earlier.

But I wasn’t certain until my good Toronto friend Leora Conway saw Tsotsi at a Toronto Film festival screening and “was beaming when she told me about it afterwards,” I wrote, “and said it made her cry at the end.”

Tsotsi may sound sentimental and manipulative, but it’s not. But neither is it sadistic or repellent in some flashy, gun-fetish way. It has a raw authenticity, but not in any kind of derivative City of God way, which speaks well for its director, Gavin Hood.

Tsotsi star Presley Chweneyagae (l.) and Hood outside Toronto’s Sutton Place hotel — Friday, 9.16.05, 8:55 am.

Tsotsi proves that suppressed emotions…the feelings that a blocked-up person would rather not feel but which won’t leave him alone…are always a stronger, more poignant proposition than a film delaing with feelings fully expressed.

Hood told me in Toronto that he’s always been “terrified” of sentimentality and “being mushy” in movies, and says that his mantra during shooting was that “there’s always got to be more going on within a character than what he lets out.”

He said he wanted to use formal compositions and a slower editing style than the one popularized by City of God “because I didn’t want to seem like I was saying ‘me too’…I didn’t want to come in second.”

Hood says he feels more of an affinity with the shooting style of director Walter Salles (The Motorcycle Diaries) and particularly Sales’ Central Station.

I had another sit-down with Hood two days ago (Tuesday, 2.21) at the Four Seasons hotel in Beverly Hills. Here’s a recording of most of it.

The Tsotsi gang

Tsotsi is one of those “it” films. You can feel the focus and the unique energy from the get-go…from Hood’s precise and well-organized direction and the elegant pho- tography to Chweneyagae’s mesmerizing performance as an ice-cold psychopath who now and then devolves into a terrified three-year-old.

It all comes together into something steady and profound. Which is why Hood will almost certainly be handed the prize on 3.5.