Websites started kicking “nuke the fridge” around roughly three weeks ago, and Newsweek‘s Periscope columnist Sarah Ball has just had a go at it. It refers to Harrison Ford hiding in that refrigerator in Indy 4 to escape the effects of a nuclear blast, etc. The main reason the term hasn’t seemed all that vital to get into from this end is that it doesn’t seem all that different or distinct from “jump the shark.”

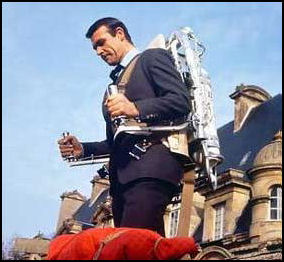

Sean Connery’s fridge moment in Thunderball.

The latter, of course, refers to suddenly being old news — having lost one’s place (position, toe-hold, whatever) in the media-culture firmament — due to some sudden, what-just-happened? tectonic shift in the state of things. The former is a cinematic term referring to some ludicrous, over-the-top piece of business that destroys the audience’s faith or sense of belief in the reality of an iconic character. Different, but not too far apart.

On top of which nuke-fridging has been around for since the mid ’60s, when a wave of pop absurdist movies (spy spoofs like Casino Royale, anarchic comedies like What’s New Pussycat?, social upheaval farces like The President’s Analyst) used deliberate and repeated nuke-fridgings as the basis of their comic attitudes.

On top of which the very first superhero fridge-nuke moment happened 42 and 1/2 years ago, so it’s not exactly a fresh concept.

The date was December 17, 1965, when Thunderball, the fourth James Bond film, opened in the U.S. Fans who’d relished Sean Connery‘s brawny machismo in Dr. No and From Russia With Love, and who had felt moderately brought down by the de-balling emphasis on high-tech gadgetry in Goldfinger, completely gave up the faith when Connery strapped on a flying backpack device during Thunderball‘s pre-credit sequence, and went whooosssshhhh….over the buildings!

The problem wasn’t just the jet pack, although that was pretty bad in and of itself. The problem was Connery wearing that idiotic crash helmet. Ian Fleming‘s James Bond wasn’t a scrupulous rule-follower. He was a bit reckless at times, liked to do things his own way. Wearing a crash helmet while flying a couple of hundred feet in the air might have been the prudent thing to do, but it looked wimpy and ridiculous and — let’s be blunt — clownish. It was the end of an era.