I’m ready and willing to ease up on my John Ford takedowns and I could really and truly go the rest of my life without writing another word (much less another article) on The Searchers.

But yesterday the Hollywood Reporter posted a Martin Scorsese essay on The Searchers — mostly a praise piece — and I feel obliged to respond, dammit. But really, this is the end.

Scorsese’s basic thought is that while The Searchers has some unfortunate or irritating aspects, it’s nonetheless a great film and has seemed deeper, more troubling and more layered the older he’s become.

My basic view of The Searchers, as I wrote three of four years ago, is that “for a great film it takes an awful lot of work to get through it.”

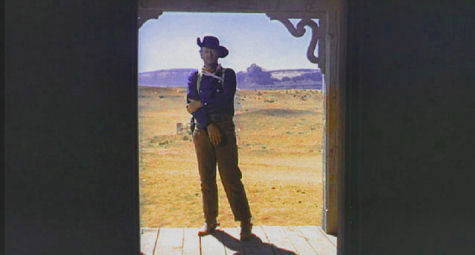

I don’t know how to enjoy The Searchers any more except by wearing aesthetic blinders — by ignoring all the stuff that drives me up the wall in order to savor the beautiful heartbreaking stuff (the opening and closing shot, Wayne’s look of fear when he senses danger for his brother’s family, his picking up Wood at the finale and saying, ‘Let’s go home, Debbie’). That said I can’t help but worship Winston C. Hoch‘s photography for its own virtues.

Scorsese’s wisest observation is that John Ford personally related to John Wayne‘s Ethan Edwards, the gruff, scowling, racist-minded loner at the heart of this 1956 film.

Ford “was at his lowest ebb” when he made The Searchers, Scorsese writes. “Ford’s participation in the screen version of Mister Roberts had ended disastrously soon after a violent encounter between the filmmaker and his star Henry Fonda.

“For Ford, The Searchers was more than just another picture: It was his opportunity to prove that he was still in control. Did he pour more of himself into the movie? It does seem reasonable to assume that Ford recognized something of his own loneliness in Ethan Edwards and that the character sparked something in him. It’s interesting to see how it dovetails with another troubled character from the same period. Like James Stewart‘s Scotty in Vertigo, Edwards’ obsessive quest ends in madness.”

Jeffrey Hunter, John Wayne

Film lovers know The Searchers “by heart,” Scorsese writes, “but what about average movie watchers? What place does John Ford’s masterpiece occupy in our national consciousness?”

Wells to Scorsese: In terms of the consciousness of the general public, close to zilch. In terms of the big-city Film Catholic community (industry aficionados, entertainment journalists, film academics and devoted students, educated and well-heeled film buffs, obsessive film bums), there is certainly respect for The Searchers but true passionate love? The numbers of those who feel as strongly as you, most of whom grew up in the ’50s and ’60s, are, I imagine, relatively small and dwindling as we speak.

I’m pleased to note that some of my complaints about Ford have at least been acknowledged by Scorsese. “A few years ago I watched it with my wife,” he writes, “and I will admit that it gave me pause. Many people have problems with Ford’s Irish humor, which is almost always alcohol-related. For some, the frontier-comedy scenes with Ken Curtis are tough to take.

“For me, the problem was with the scenes involving a plump Comanche woman (Beulah Archuletta) that the Hunter character inadvertently takes as a wife. There is some low comedy in these scenes: Hunter kicks her down a small hill, and Max Steiner’s score amplifies the moment with a comic flourish. Then the tone shifts dramatically, and Wayne and Hunter both become ruthless and bullying, scaring her away. Later, they find her body in a Comanche camp that has been wiped out by American soldiers, and you can feel their sense of loss. All the same, this passage seemed unnecessarily cruel to me.”

Here’s what I wrote way back when:

“John Ford‘s movies have been wowing and infuriating me all my life. A first-rate visual composer and one of Hollywood’s most economical story-tellers bar none, Ford made films that were always rich with complexity, understatements and undercurrents that refused to run in one simple direction.

“Ford’s films are always what they seem to be…until you watch them again and re-reflect, and then they always seem to be about something more. But the phoniness and jacked-up sentiment in just about every one of them can be oppressive, and the older Ford got the more he ladled it on.

“The Irish clannishness, the tributes to boozy male camaraderie, the relentless balladeering over the opening credits of 90% of his films, the old-school chauvinism, the racism, the thinly sketched women, the “gallery of supporting players bristling with tedious eccentricity” (as critic David Thomson put it in his Biographical Dictionary of Film) and so on.

The closing shot of John Ford’s The Searchers

“The treacliness is there but tolerable in Ford’s fine pre-1945 work — The Informer, Stagecoach, Young Mr. Lincoln , Drums Along the Mohawk, They Were Expendable , The Grapes of Wrath and My Darling Clementine .

“But it gets really thick starting with 1948’s Fort Apache and by the time you get to The Searchers, Ford’s undisputed masterpiece that came out in March of 1956, it’s enough to make you yank the reins and go ‘whoa, nelly.’

“Watch the breathtaking beautiful new DVD of The Searchers, and see if you can get through it without choking. Every shot is a visual jewel, but except for John Wayne‘s Ethan Edwards, one of the most fascinating racist bastards of all time, every last character and just about every line in the film feels labored and ungenuine.

“The phoniness gets so pernicious after a while that it seems to nudge this admittedly spellbinding film toward self-parody. Younger people who don’t ‘get’ Ford (and every now and then I think I may be turning into one) have been known to laugh at it.

“Jeffrey Hunter‘s Martin Pawley does nothing but bug his eyes, overact and say stupid exasperating lines all through the damn thing. Nearly every male supporting character in the film does the same. No one has it in them to hold back or play it cool.

“Ken Curtis‘s Charlie McCorry, Harry Carey Jr.’s Brad Jorgensen, Hank Worden‘s Mose Harper…characters I’ve come to despise.

“You can do little else but sit and grimace through Natalie Wood‘s acting as Debbie (the kidnapped daughter of Ethan’s dead brother), Vera Miles‘ Laurie Jorgenson, and Beulah Archuletta‘s chubby Indian squaw (i.e., ‘Wild Goose Flying in the Night Sky’)…utterly fake in each and every gesture and utterance.

“I realize there’s a powerful double-track element in the racism that seethes inside Ethan, but until he made Cheyenne Autumn Ford always portrayed Indians — Native Americans — as creepy, vaguely sadistic oddballs. The German-born, blue-eyed Henry Brandon as Scar, the Comanche baddie…’nuff said.

“That repulsive scene when Ethan and Martin look at four or five babbling Anglo women whose condition was caused, we’re informed, by having been raised by Indians, and some guy says, ‘Hard to believe they’re white’ and Ethan says, ‘They ain’t white!’

“I’ll always love the way Ford handles that brief bit when Ward Bond‘s Reverend Clayton sees Martha, the wife of Ethan’s brother, stroking Ethan’s overcoat and then barely reacts — perfect — but every time Bond opens his mouth to say something, he bellows like a bull moose.”

Final thought: The more I think about the stuff in Ford’s films that drives me crazy, the less I want to watch any Ford films, ever. Okay, that’s not true but the only ones I can stand at this point are The Horse Soldiers, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, The Grapes of Wrath, The Informer, The Lost Patrol, The Last Hurrah and, believe it or not, Donovan’s Reef.