Gilbert Stood Tall

There are two things you need to know about Penn Gillette and Paul Provenza’s The Aristocrats (ThinkFilm, 7.29 limited). One, it’s quite funny but not in the usual way — it makes you laugh and also say at the same time, “Am I really laughing at this?” And two, you need to see it not just for the humor, but for the journey it takes you on.

There’s a quote made famous by the late Michael O’Donoghue that says “making people laugh is the lowest form of humor.” This is one of the few films I’ve seen that actually seems to get what O’Donoghue was on about.

Gilbert Gottfried, not just one of the stars of The Aristocrats but the star…at Caroline’s following New York premiere — Tuesday, 7.26, 11:15 pm.

This is a movie that basically gets laughs out of the different ways that gifted comics get laughs out of the same joke. And it’s really something to find yourself laughing at the tenth or the eighteenth or the twenty-fifth version of this rancid concoction…something because “the joke” isn’t all that funny, despite its reputation as a landmark gag that every major comic has passed along and had fun with.

The joke is basically about a man making a pitch to a talent agent with a claim that he and his family has a great act, and the agent agreeing to sit down and watch them perform it. The act is foul… in defiance of every tenet of civilized, moralistic behavior. And then the agent asks what the act is called and the man says, “The Aristocrats.”

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

I happen to agree with Drew Carey that the joke works better if you do the arm thing (as Jillette and Provenza are doing in the photo below) when you say “the Aristocrats.” But this doesn’t really change what Pat Cooper says early on in the film, which is that “the joke sucks!”

And that’s not the point.

You start laughing at this stupid-ass gag after the third or fourth telling, and the more you laugh the less you care about laughing, and the more you’re enjoying the talent and inventions and personalities of the joke-tellers and sampling the dozens of ways this relatively mediocre gag can be made to work.

It’s odd, but sharing in the enjoyment of telling a lame joke really well gradually makes the experience of laughing at a genuinely funny joke pale in comparison.

This is one of those movies you have to see because you have most likely never heard of, much less considered, the acts described in the various renditions of the joke. And to mull it all over in the company of strangers feels like some kind of therapy.

(l. to r.) The Aristocrats maestros Paul Provenza and Penn Jillette

It’s an oddly liberating thing to be sitting with a group of people and acknowledging (by the evidence of constant laughter) our gross animal commonality.

The experience is made extra-palatable by watching all these cool-cat big-name comics — George Carlin, Paul Reiser, Martin Mull, the great Gilbert Gottfried, Robin Williams, Bob Saget, Whoopi Goldberg, Jason Alexander, Eddie Izzard, Drew Carey, Eric Idle, et. al. — serving as goaders and ringleaders.

I said last January that the funniest bit of all is a tape of Gilbert Gottfried telling the joke at a Friars Roast of Hugh Hefner that took place in Manhattan only a couple of weeks after 9/11. He’s like Zeus up there on the mike…like Alexander the Great.

Nobody wanted to push any envelopes at this Friars Club thing, for obvious reasons. Everyone wanted to go easy — some comics wondered if it was even appropriate to try and be funny at such a time. What does Gottfried do? He gets up there and tells a joke about catching a connecting flight out of the Empire State building.** Somebody in the audience shouts out, “Too soon!”

It was at this point, more or less, when Gottfried began telling the Aristocrats joke and brought down the house.

It’s not just that he tells it with typical Gottfried-ian gusto, or that other comics in the room (like Rob Schneider) are literally on the floor. It’s the metaphor of what he’s doing.

(l. to r.) Gottfried at the Hugh Hefner roast almost four years ago in New York City, a couple of weeks after 9/11.

People of moderation and mediocrity are always telling creative people not to stick their necks out and tow the conventional moral line. Gottfried ignored this and rolled the dice and tapped into the emotional undercurrent and made it into something else. Laughter has always been about expunging hurt, and this time there was a lot to go around.

Gottfried’s routine also showed that truly creative people never second-guess themselves. They never sand down their material to fit what they’ve been told people supposedly want or don’t want. They go for it and let the chips fall.

I also love that when you bring this up to Gottfried he shrugs and goes, “Okay…that sounds good.” What he means is that he didn’t do anything deliberately, he didn’t think about it — it just happened.

The second funniest bit in The Aristocrats is Kevin Pollak telling the joke in the voice of Christopher Walken, or in the voice of Walken’s Sicilian goombah in True Romance.

The third funniest bit is Martin Mull telling the “kiki” joke (the one with the two anthropologists captured by loin-clothed natives and being told they can either die or suffer “kiki” and…you know how it goes), but with an Aristocrats substitution.

The fourth funniest joke is that clip of one of the little South Park guys telling it.

** The exact joke went, “I have a flight to California. I can’t get a direct flight. They said they have to stop at the Empire State Building first.”

Malleable Sheep

Adam Curtis’ The Century Of The Self is a nearly four-hour, BBC-produced documentary that’ll begin showing at Manhattan’s Cinema Village on August 12. Trust me, it’s worth the four hours and then some. It’s quite simply the most intriguing, audacious and insightful study of publicity, mass psychology and Orwellian mind control ever assembled.

The Century Of The Self is the pretty much untold and appalling story of the creation of psychological selling points in commercial and political marketing, and how this led to the culture of “me” and the expansion of mass-consumer societies in Britain and the United States. How was the all-consuming self created, by whom, and in whose interests?

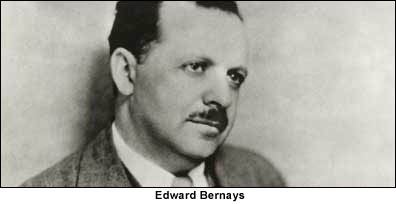

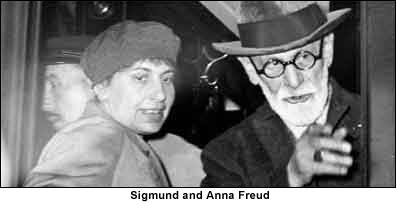

Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, and his nephew Edward Bernays, the father of modern public relations and the concept of “spin,” are the genteel ogres at the heart of Curtis’s social history.

The Century Of The Self is the story of Bernays’ amazing influence, beginning in the 1920s, upon the techniques of selling and mass persuasion…techniques based upon the insights into the human psyche that his illustrious uncle made famous.

Curtis’s film says in essence that Freud’s uncovering of the drives within the human mind — and particularly the influence of our subconscious urges — has changed the world by way of Bernay’s seminal revolution in public relations techniques, the results of which are everywhere today, especially in big-time politics.

Before Bernays came along advertising and political promotion was essentially about laying facts before the public and leaving them to decide to buy or not buy based on rational evaluation. Bernays’ big idea was getting industry to start pitching products and services to people’s unconscious — to pull them in based on what they emotionally wanted, but didn’t necessarily need.

An explanation on a BBC website puts it well: “By introducing a technique to probe the unconscious mind, Freud provided useful tools for understanding the secret desires of the masses.

“Unwittingly, however, his work served as the precursor to a world full of political spin doctors, marketing moguls, and society’s belief that the pursuit of satisfaction and happiness is man’s ultimate goal.”

Telluride Film Festival director Tom Luddy was the one who turned me on to The Century of the Self during the 2003 San Francisco Film Festival.

Luddy told me soon after that journalist/author Christopher Hitchens is a big fan of this film; ditto Orville Schell, Dean of Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism.

Schell, said Luddy, had thought one way for The Century Of The Self to be seen in this country would be for PBS’s Frontline series to air it. A call or two suggested otherwise. Brilliant and on-target as many believe Curtis’s documentary to be, it may, by the standards of American TV journalism, not be “balanced” enough.

Self says in essence that we live in a country run by leaders who have never trusted the voters and have always sought (successfully, in most ways) to “control” our thinking and appetites and political allegiances. Such a declaration would almost certainly ignite controversy.

A show like Frontline, says Luddy, would “have to have two sides…they’d have to have this quote-unquote ‘objectivity’…and this film is a polemic…it suggests that our democracy is manipulated by people who believe the voting public is fundamentally irrational.”

Schell, who describes Luddy as a kind of Johnny Appleseed of new, see-worthy films, agrees that The Century Of The Self “is a natural to be aired someplace because it’s a very good film.

“But I don’t know that it’s a natural for ‘Frontline.’ I don’t think that show lends itself well enough to this kind of mission statement. But I think it’s an amazing project, and precisely the kind of thing American TV should be providing.√ɬ¢√¢‚Äö¬¨√Ǭù

However, says Schell, “If a film such as this were to appear on a network, I think I’d have a heart attack. The tragedy is that it’s so unimaginable that a film such as this could be shown, much less made, by any of the apparatus that has come to be known as American TV.”

I called Curtis in London in June ’03 and asked about what has been perceived by some as a lack of balance in this film. He said the mode of presenting differing points of view about a controversial subject is obviously a venerated approach, but it’s now old hat.

“Those days of journalism are over,” he said. “That was the sort of journalism that was formed during the Cold War. Our job is to actually tell a story, but it’s not a polemic — it’s a particular story told from a particular viewpoint.

“In the old days everyone knew what was happening on the world political stage…there was a big struggle, that was it. Now there isn’t an agreed-upon story, an agreed-upon position to be adopted. Christopher Hitchens has said that the job of modern journalism is to make sense of all these fragments that you can argue for or against.”

The Century of the Self is composed of four one-hour chapters titled “Happiness Machines,” “The Engineering of Consent,” “There is a Policeman Inside All Our Heads: He Must Be Destroyed” and “Eight People Sipping Wine in Kettering.”

There’s a whole rundown — photos, chapter breakdowns, links– about the series on a BBC site that will fill in some of the gaps.

This doc really deserves to get out there and be seen as widely as possible by New York media types, so it’ll get some decent exposure when the DVD comes out.

Ancient Pelican

Don’t ever expect movies that you liked as a kid to stand up when you see them again as an adult. It’s almost better to leave them in your head than confront the reality of what they really are and were.

I haven’t seen William Wellman’s The High and the Mighty since I was 11 or 12, when I caught it on the tube in a pan-and-scan version. I’ve never seen this 1954 film in widescreen (it was shot in the somewhat wider CinemaScope used in the early to mid ’50s, which had an aspect ratio of about 2.55 to 1). And I have these hazy notions of it being an emotionally affecting thing (I’ve always been a sucker for Dimitri Tiomkin’s emphatic scores) and John Wayne exuding a certain authority in the role of the middle-aged co-pilot.

I guess this means I’m going to at least rent the two-disc special edition DVD when it comes out August 2nd, especially with all the extras….but I’ve got my fingers crossed.

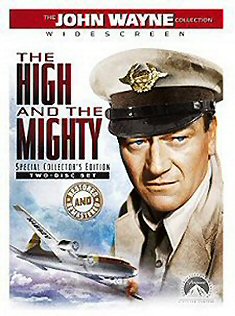

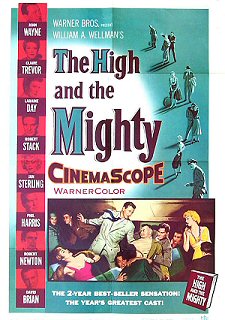

Jacket cover for Paramount Home Video’s DVD of The High and the Mighty (due August 2nd) and one-sheet issued during film’s 1954 theatrical release.

The High and the Mighty is about a commercial flight from Honolulu running into trouble during a flight across the Pacific to San Francisco, and a lot of people — the crew among them — becoming more and more persuaded that the plane and its passengers are headed for the drink.

It was Hollywood’s first multi-character soap-opera disaster movie, and was thought to be a little sappy and sentimental even for its day, and we all know how cornball characteristics tend to worsen over time.

A pen-pal journalist who’s seen the DVD says The High and the Mighty “is worse than anyone remembers…hopelessly stodgy and dumb, and very boring unless you’re into laughing at it.”

He trashed the cockpit POV shot when the injured plane finally lands at San Francisco airport and the landing lights form a crucifix and Wayne says, “Now I lay me down to sleep.” Okay, overbaked…but I flew across the country one time in a Beechcraft Bonanza four-seater and when you land at night the runway lights do look like a cross. (I wonder what the lights look like if the pilot of a damaged plane is a Muslim or a Buddhist.)

It’s all speculation until I see it, but here’s one thing I know for sure: the jacket art on the DVD makes it look like something from one of those cheapo companies who put out public-domain films.

Quality level DVDs either use some representation of the original ad art or come up with a modern variation or substitution that’s even better looking. Paramount’s High and the Mighty jacket art does neither. That close-up shot of Wayne in his airplane pilot’s uniform along with that drawing of an airplane looks like it’s aimed at the K-Mart crowd.

Grabs

ThinkFilm honcho Mark Urman (l.) at Tuesday night’s after-party at Caroline’s following the premiere of The Aristocrats. I don’t know the guy on the right.

Actress Leigh Spofford (Kinsey, The Human Stain) with L.M. Kit Carson (l.) at the 7.26 Aristocrats party. Spofford is the star of Cat’s Paw, a thriller that’ll soon be shooting in and around Oxford, England, and will costar John Shea. Carson is exec producing. Alun Harris is directing the film, which Carson describes as “Pulp Fiction meets Chariots of Fire.” Spofford played Liam Neeson’s daughter in Kinsey. (Apologies for having gotten the title wrong earlier — Carson and Spofford made a short together last year, and this was the source of the confusion.)

Captives in underground blast furnace-sweat box — Sunday, 7.25, 6:40 pm.

Would a caption make a difference? First Avenue just north of 3rd Street — Sunday, 7.24, 11;20 pm.

First Avenue around 3rd or 4th Street — Sunday, 7.24, 10:50 pm.

Park Avenue looking south from 61st Street — Monday, 7.25, 10:50 am.

Daily News columnist Lloyd Grove, Dick Cavett at Tuesday’s Aristocrats party.

Why do the women reading paperback books in subways and airport lounges always seem to be reading mass-market fiction? Why don’t I ever see one, just one, reading a book by, say, William Faulkner or Gore Vidal?

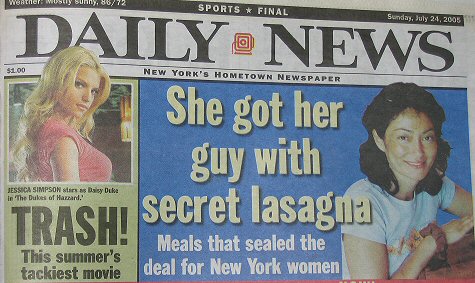

Cover of last Sunday’s New York Daily News, lying on top of garbage in waste basket on corner of 9th Avenue and 39th Street.

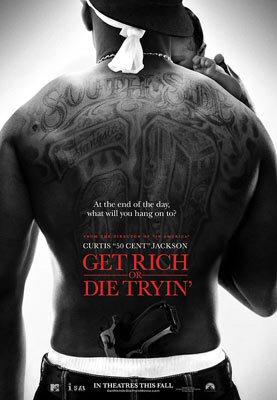

One-sheet for Jim Sheridan’s Get Rich or Die Tryin’ which only just wrapped two or three weeks ago but is coming out in November. That may not be a super-fast turnaround by Otto Preminger standards (he finished shooting Anatomy of a Murder in May of ’59 and had it on the screen two months later), but it’s pretty quick by today’s.