Please read Owen Gleiberman‘s 3.1 Variety essay, “The Success of The Invisible Man Reveals the Fallacy of ‘Get Woke, Go Broke.'”

The article is in fact required reading for the contrarian dickheads who accused me yesterday of sounding like a broken record for merely pointing out the woke political undercurrent in The Invisible Man — for saying the film was rotely efficient as far as it went but at the same time was brandishing a certain socio-political consciousness.

Bobby Peru was the worst of them. As I wrote yesterday, “In Peru World films can only be made or processed as purely neutral artistic creations…there can be no such things as political or cultural influences.” He lies, he obfuscates, he blows smoke, he chokes on it.

I’ll admit that in my initial review I didn’t elaborate upon the real-world metaphors in The Invisible Man, partly because I felt numbed by the familiar horror-thriller shocks (Benjamin Wallfisch‘s assaultive score in particular) and partly because the subtext felt built-in from the get-go. But that aside…

Gleiberman #1: “Over the last few years, Hollywood’s mostly superficial onscreen attempt to deal with issues of women’s empowerment has resulted in a track record dotted with box-office failure, and this has given rise to a certain knee-jerk misogynistic appraisal of that phenomenon. It goes back, in a way, to the Ghostbusters remake, which was greeted with undisguised hostility before it was ever released. And when it turned out to be a so-so movie, it got beaten up on as if its failures, comedic and financial, somehow meant something.”

Gleiberman #2: “You could say that the premise of just about every woman-in-peril movie is that toxic masculinity is out there, that it’s scary and violent and dangerous, and that it’s coming for you. (That was true decades before the term ‘toxic masculinity’ was invented.) But when you watch The Invisible Man, the fearful and cunning new thriller starring Elisabeth Moss as a woman who fights off the cat-and-mouse stalking moves of a man she can’t see (and who therefore, to everyone else, doesn’t exist), what’s new is the heightened awareness of what it feels like — what it means — to be a woman in trouble whom no one believes. That’s what makes the film an expression of the #MeToo world.

Gleiberman #3: “The dimension that lifts the movie above Sleeping with the Enemy or a glossy FX potboiler like Paul Verhoeven’s Hollow Man is the dramatic finesse with which it turns Cecilia’s predicament into a potent projection of something that’s now at the heart of the culture. What I wanted to say is that her predicament — she’s under attack but people think she’s crazy, because her abuser is (supposedly) dead and (in reality) invisible — works as a metaphor.”

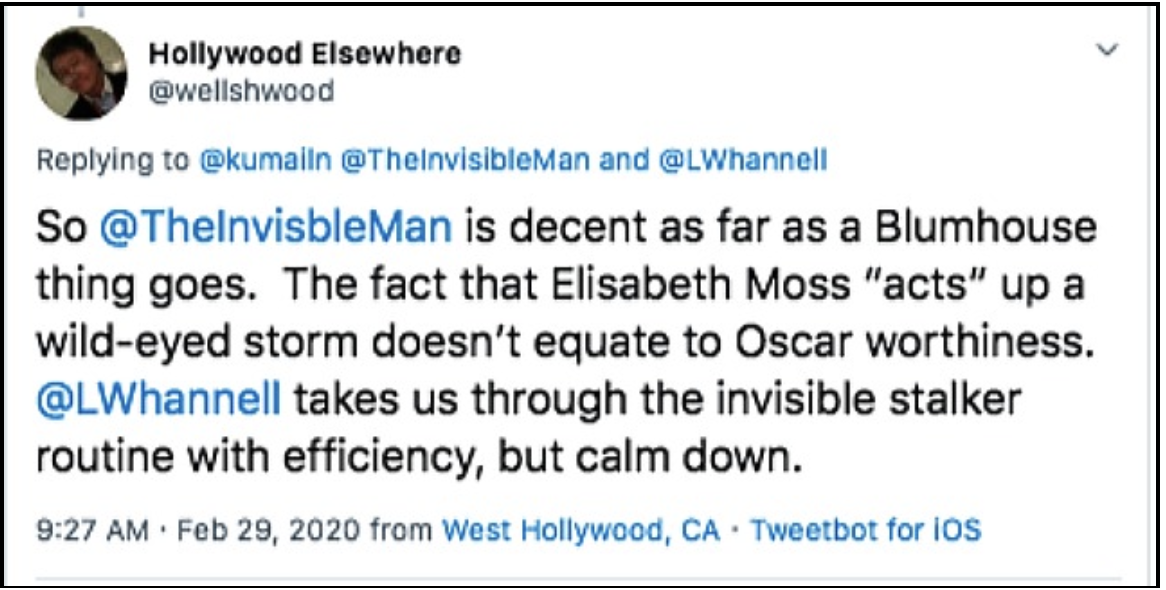

HE to Gleiberman: “Dramatic finesse”? This is a Blumhouse film deploying the usual suspense-and-shock tactics. And to emphasize her anxiety and panic, Moss does everything but bleed from her eyeballs.”

Gleiberman #4: “Part of the power of movies, even popcorn movies, is that they’re encoded with metaphors that charge the experience of watching them with meaning. The issue of women not being believed when they level charges of harassment (or worse) has moved to the forefront of our national conversation. When it comes to matters like this, the dismissal of women’s claims has been habitual and institutional. You could also say, though, that it’s something more — that it’s mythological. The reticence to acknowledge (and to act upon the knowledge of) sexually abusive behavior has been, to a degree, woven into the fabric of our society.

Gleiberman #5: “No, the movie isn’t an editorial; it’s a piece of entertainment. But when it’s over, maybe you walk out with your empathy, and your awareness of what’s going on in the world, a bit heightened.”