Heads Will Roll

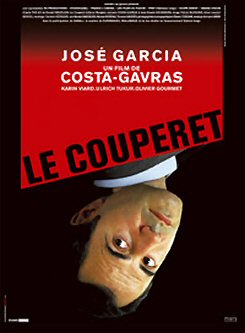

The stand-out thing about The Ax, the new Costa-Gavras satire that opened the San Francisco Film Festival on Thursday night (4.23), isn’t that it’s utterly black. That’s obvious and easily digestible from the get-go. We’re used to this, in any case.

The money element for me — the selling point — is that it’s so bracingly dry. And tightly plotted and suspenseful. And the fact that it never quite tips into being a reassuring “comedy.”

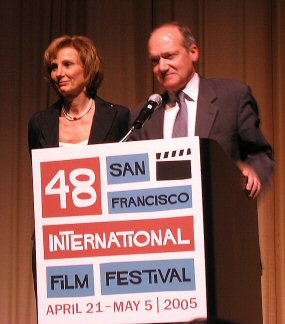

The Ax director and co-writer Costa-Gavras, producer (and wife) Michele Ray-Gavras during reception at home of Frederic Desagneaux — Friday, 4.22.05, 7:10 pm.

That in itself means a lot of people are going to find it a little too cool for their liking. This would be short-sighted of them, of course, because what Costa-Gavras has accomplished here is a very impressive balancing act.

The lead character, a kind of cold-blooded killer, could have been repulsive or at least alienating if the director’s mood and attitude had been off just an inch or two off. The Ax is lightly, ironically, mordantly humorous…and at the same time needling and nerve-wracking.

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

If you’ve seen The Corporation (which recently came out on DVD in a great two-disc package), you know the bedrock theme is that corporations are psychopathic. The Ax, which is taken from a 1997 Donald Westlake novel, flips this over and asks, what if a guy in a tough financial spot acted with the same win-at-all-costs, social-mores-be-damned attitude of a typical corporation?

What if an out-of-work guy, in other words, decided to increase his chances of finding a new job by killing the guys who appear to be his chief competitors?

Bruno Davert (Jose Garcia), 41, is a former top-level executive at a French paper mill who’s been fired (along with several hundred others) because the company decided to go with cheaper labor in another country. He hasn’t found a new job in over two and a half years, but he’s got his eye on a position at a big paper company called Arcadia.

The only thing (or things) standing in his way, he figures, are six or seven unemployed guys whose qualifications are as good if not better than his own. So he decides one day to eliminate them. He turns out to be a sloppy hit man, but he’s persistent and gets the job done.

Then the cops come knocking because they’ve noticed that a string of murders all involve male victims who worked for paper companies. And then the screws tighten further.

The twists and turns that follow make it a natural thing to root for Bruno, despite his constant murdering. There are few things in a drama as unnerving or even surreal as a truly sympathetic fiend. The Ax isn’t exactly “realistic” — the slightly arch and aloof tone underlines this — but it’s real enough to sink in and feel like something that’s part of our world.

Costa-Gavras seems to be saying to his audience, “Go a little easy on this guy. He may be killing one innocent victim after another, but he can’t find work and he’s really hurting and so he’s not really that bad. In fact, he’s almost blameless. If you want to blame someone, blame the corporations…blame globalism.”

The final irony of this film is that Bruno, his story and the underlying morale are not extreme elements. Every character, everything that happens is presented in moderate terms.

Bruno is a basically moral, considerate, middle-class family man who has been pushed into a state of almost animal-like ferocity. And yet he crosses the line as discreetly as he can manage, and then he is the recipient of incredible luck, and things finally work out. It’s all very neat and tidy.

The more I think about The Ax, the more I’m convinced it’s Costa Gavras’ best film — the most focused and most satisfying — since Missing (’82).

I respected his last film, Amen, which was based on The Deputy, a play about Vatican immorality during World War II, but I wasn’t blown away by it.

The Ax is certainly more assured than Mad City , Costa-Gavras’s 1997 film that was also about an average guy (John Travolta) pushed to desperate acts after losing his job.

The Ax joins a group of films that have come out over the last two or three years about the effects of corporate-think upon average middle-class people.

The most respected of these among elite film critics is Laurent Cantet’s Time Out, about a middle-aged husband and father who embarks on a massive charade in order to hide from his family the fact that he’s been laid off.

I’m not a huge fan of this film, personally. I respected it but I vaguely hated it. I felt drained by the passively dull and pig-eyed main character and the oppressive lethargy that seemed to seep out of the film at every turn.

There was also Cantet’s Human Resources, which portrayed the scruples of a young white-collar comer who finally decides to reject the rules of the game.

My favorite so far has been Jean-Marc Moutout’s Violence des Echanges en Milieu Tempere, which I saw at the Locarno Film Festival in the summer of `03. The title roughly translates into Violent Changes In The Workplace, although the English title is Work Hard, Play Hard. It was never distributed in the U.S. or even, as far as I know, put out on DVD.

I wrote back then that “as a portrait of what it means to be an agent of icy efficiency in a heartless business scheme, it’s one of the most riveting and quietly unsettling moral tales I’ve seen in a long while.”

Streets of San Francisco

San Francisco Film Festival Executive Director Roxanne Messina Captor receiving a Chevalier Order of Arts and Letters medallion from French Consul General Frederic Desagneaux — Kabuki Theatre, 4.22.05, 8:12 pm.

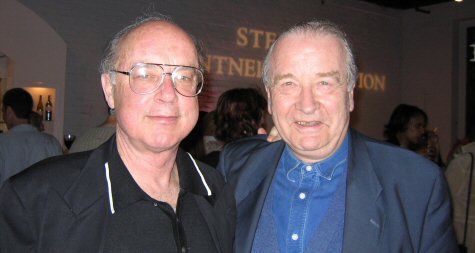

San Francisco Film Festival programmer and Telluride Film Festival kingmaker Tom Luddy (l.) and the festival’s French cinema programmer Michel Ciment at an outdoor opening night party for 48th annual San Francisco Film Festival at Girhardelli Square.

The great Bobby Yang on violin during a performance of a four-piece quasi-jazz group at VIP lounge at Ghirardelli Square.

A jazz-lite group performs during Thursday night’s outdoor opening-nighter at Ghirardelli Square.

In north-facing living room of the home of Frederic Desagneaux, French Consul General of France, during 4.22 reception, at 7:20 pm.

Fine Madness

It’s out about eight months too late but there’s no sense crying over spilt milk and it doesn’t really matter anyway, because Nicholas Jarecki’s The Outsider is a surprisingly strong film.

It doesn’t simply capture the essence of director-writer James Toback in all the right ways (smartly, perceptively, humorously), and I don’t mean to imply that doing this alone would be some kind of marginal accomplishment.

I know Toback personally, and can say with some authority that Jarecki gets all the right quotes and insights and whatnot, and determines the measure of one of the nerviest and most relentless uber-mavericks in the film business today.

I’ve said several times in this column over the last five or six years that I admire Toback for his wit and smarts and maverick spirit. I’m especially taken by his moxie and tenacity in making his films his own way.

Harvey Keitel, James Toback during shooting of Fingers some 27 or 28 years ago.

And with one exception, I really like his movies. I loved Two Girls and a Guy and Black and White. I was even okay with most of Harvard Man. The irony is that the one Toback film I’m not terribly keen on is When Will I Be Loved?, the making of which is the focus of Jarecki’s doc.

But even a second- or third-tier Toback film is worth seeing, I feel, because of the aliveness of the personality behind it. Go to Jarecki’s site for The Outsider and listen to Toback’s comments during a radio interview with Joe Franklin, and you’ll have a clue about what I mean.

The Outsider is showing this evening (Saturday, 4.23) as an attraction of the Tribeca Film Festival at the Regal Battery Park, at 8:30 pm. It’s also showing at the Pace Schimmel Center on Friday, 4.29, at 9 pm, and on Sunday, May 1st, at the Regal Battery Bark at 1:15 pm.

Toback made When Will I Be Loved? because his producer, Ron Rothholz, found a financier who would put up a few million to make a film for tax reasons, but Toback would have to shoot the whole thing in about three weeks’ time, and with almost no time to prepare.

A Manhattan-based relationship drama shot in a semi-improvised fashion similar to his Black and White, When Will I Be Loved? is a somewhat cynical, more-than-frankly-sexual drama that stars Neve Campbell, Fred Weller and Dominic Chianese.

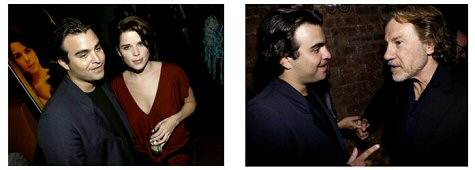

(l.) The Outsider director Nick Jarecki, When Will I Be Loved? costar Neve Campbell at reception; (r.) Jarecki and Harvey Keitel.

It’s hard to make a really exceptional film, much less a good one, in three weeks’ time, especially if you’re working from a script that has only been generally blocked out and needs to be somewhat improvised, as was the case here. It says a lot for Toback’s fast footwork that When Will I Be Loved? turned out as well as it did.

In the view of Roger Ebert, Christian Science Monitor critic David Sterritt, Newsday‘s Gene Seymour and other front-line critics, it was more than a pretty good effort. But Toback and Rothholz had a seriously rough time finding a distributor, and for a while there it looked like it might have to go straight-to-video.

What gives Jarecki’s doc that extra dimension is watching Toback face resistance from distributors and perhaps (and I’m basically talking impressions here) start to wonder deep down about whether he’s played it right this time. There’s something about seeing a guy who’s usually very confident and even a bit of a boaster and a swaggerer go through anger, denial, bargaining, additional shooting, etc.

The irony is that When Will I Be Loved?, which was finally acquired by IFC Films, performed decently where it played, and the DVD has brought in about $5 million so far, which isn’t nothing.

I spoke to Jarecki a few days ago. He called himself “the new Leni Reifenstahl,” and I leave readers to interpret that one all on their own.

Neve Campbell (l.) and Toback on the set of When Will I Be Loved?.

He concurs that The Outsider‘s final act, in which Toback suffers his moments of doubt and pain, lend an extra dimension.

“The reality is that you make a crazy movie that doesn’t play by the rules and everybody says what the fuck is this? The reality is that he got hurt by the response to it. Jim makes his films up…and his personality in general is partially an example of how you have to be in the movie business, because he builds up a tremendous defensive wall.”

The talking-head admirers in The Outsider include Woody Allen, Robert Downey, Jr., Harvey Keitel, Mike Tyson, Neve Campbell, Norman Mailer, Brooke Shields, Barry Levinson, Robert Towne, Brett Ratner, Roger Ebert, Damon Dash, Woody Harrelson, Jim Brown, John Calley, Bijou Phillips, Jeff Berg, Dominic Chianese, and Power from Wu-Tang Clan.

We’ve all read George Bernard Shaw’s quote about how “reasonable men always try to adapt themselves to fit the world around them, while unreasonable men persist in trying to adapt the world to fit themselves, and therefore all progress is made by unreasonable men.” Or words to that effect. Take the point or not.

Doesn’t Matter

I don’t think it matters that much if some of the big-name critics are taking shots at Sydney Pollack’s The Interpreter (Universal, opened 4.22). All that counts is whether it’s been smartly promoted and, more to the point, whether or not there’s an appetite out there for this level of sophistication.

But it’s a curious thing to see a film you absolutely know to be a smart, above-average thriller be hammered and picked apart by people who know the difference between crap and good-enough quality, and who seem to have a stick up their ass.

You may not come out of this movie weeping or needing a double Jack Daniels to calm your nerves, but you’d have to have a pissy attitude not to admit that it’s a totally assured,bump-free ride. Smooth and crafty and well-ordered, and no trouble to sit through at all.

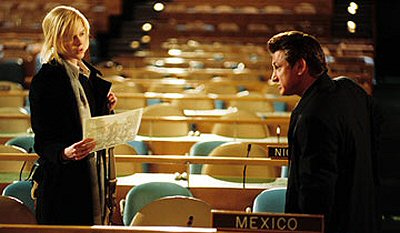

Sean Penn, Nicole Kidman in Sydney Pollack’s The Interpreter.

That sounds like damnation with faint praise. What I mean is, The Interpreter is a finely tuned engine. It’s a Bentley. Once it kicks in there’s no shifting in your seat or looking at your watch.

I’m a little perplexed by Eleanor Ringel Gillespie’s review in Friday’s (4.22) Atlanta Constitution. She calls it classy, well-honed, deftly organized…and then out comes the knife.

“As sleek and solid as a late ’50s Cadillac, The Interpreter is very much your father’s — perhaps, your grandfather’s — thriller,” she writes. “And that’s a good thing.”

Gillespie means that the kind of careful, exacting craft that Pollack put into making this film is a dying discipline. But she also knows that the notion of any movie being seen as appealing to fathers and grandfathers terrifies studio executives, agents, producers. She couldn’t have wounded Pollack more if she had literally stabbed him.

The Seattle Post Intelligencer‘s William Arnold is another wounding admirer: “Made with the intelligence, glossy production values and classic filmmaking technique that characterizes Pollack at his finest,” he calls The Interpreter “an elegant entertainment of the old school.”

Obviously there’s a consensus of opinion here. I even heard the term “old school” (or “old-fashioned”) from a guy who worked on the film, so I guess I’m in denial.

I suppose there are things in The Interpreter that feel a bit shop-worn. I just hate equating good craftmanship with “old-school.” Jesus, think of the implications.

Are they saying it moves too slow? They’re nuts. William Steinkamp’s cutting is about as brisk and economical in the service of this kind of complex story as anyone can expect, and it’s faster and punchier than the cutting Pollack used for his last New York thriller, Three Days of the Condor, which came out in ’75.

In all the important ways, The Interpreter strikes me as fully caught up in the here and now. It just doesn’t have that visual-energy-for-visual-energy’s-sake thing that a lot of 40-and-under directors love to put in their films. And the naysayers are telling me that’s a bad thing?

Is it really such a rickety, old-fashioned pleasure to enjoy careful strategic weaving of dozens of story strands that have to fit together just so and pay off in just the right way?

Are we saying that thrillers that don’t necessarily add up or which try to wallop their way past difficult plot points are the kind of films that younger paying audiences prefer?

I give up. I’m talked out on this film. The duel is over. It’s in the public’s hands now.

Saturday figures suggest The Interpreter will earn in the vicinity of $20 to $22 million this weekend. Not bad. Something tells me the hold factor won’t be all that great next weekend, but let’s keep our cynicism in check.

DVD Commentaries

I’ll be popping in some of the letters I got about this subject on Sunday morning. I don’t know why it’s taking me so long to put this column up, but I feel like I’m covered in gelatin and stuck in some kind of eerie slow-mo realm.

Absent Ace

“I recently came across the fantastic Billy Wilder film Ace in the Hole (re-released as The Big Carnival). Unfortunately, it’s only available on a rare VHS copy (I found it at Vidiots in Santa Monica) and the dialogue is out of sync for most of the film.

“You often use your column to promote films deserving of the deluxe DVD treatment and I think this one more than qualifies. This is a media satire, after all, that is possibly even more relevant today than when it was released.

“I was going to point to Elia Kazan and Budd Schulberg’s A Face in the Crowd as another example of both a great media satire and a film criminally overlooked on DVD, but Amazon now shows that a DVD version will be release on May 10.

“Just thought I’d bring that to your attention. Do with it what you will.” — Chris Casper , Los Angeles, CA.

Wells to Casper: I love Ace in the Hole and yes, of course, it should be digitally restored and released on DVD. It’s not that bitter by today’s standards, although it was seen as overly so in 1951 when it was first released.

I’ve always loved Ace in the Hole‘s dialogue, which came from Wilder, Walter Newman and Lesser Samuels.

I adore that rant from Douglas’ newspaper reporter character about how he prefers those “four spindly trees” in front of Rockefeller Center over the vast wonders of nature commonly found in Hicksville because he can’t stand the hicks.

Jan Sterling to Douglas after an abusive verbal smack-down: “I’ve known some hard-boiled eggs in my time, but you’re twenty minutes.”

Room #501, Rex Hotel, 562 Sutter Street, San Francisco.

Schmoozers at Castro theatre prior to opening-night showing of the new Costa-Gavras film, The Ax (i.e., Le Couperet).