The great actor, producer and director Norman Lloyd passed earlier today at age 106.

I was so taken by his performance as a blind but very skilled English professor in Curtis Hanson‘s In Her Shoes that I asked to chat with him. Two encounters happened, both in September ’05. We did a phoner, and then I was invited to take snaps at his Mandeville Canyon home. We talked for another hour or so.

Norman Lloyd, 90, is in only three scenes in In Her Shoes and is on screen maybe seven or eight minutes, but his performance is one of the most poignant notes in a film that has more than a few of them.

It’s not one of those burn-through-the-screen performances (along the lines of, say, Beatrice Straight‘s fight-with-Bill-Holden scene in Network). It’s more like a coaxer. You can sense Lloyd’s intellectual energy and zest for life despite his character’s withered state, and you can feel and admire the tenderness he shows to Maggie …tenderness mixed in with a little classroom discipline.

He plays a sightless retired college professor who prods Diaz’s Maggie character, who is dyslexic and can’t read a billboard slogan without stumbling, into reading poetry to him — specifically a poem about loss and emotional guardedness by Elizabeth Bishop.

At first Maggie is reluctant, then she agrees to read to him…slowly, almost painfully…I have a dyslexic friend and she doesn’t read this slowly…but she gradually improves.

Then Lloyd prods her into explaining what she thinks of the poem. She tries to duck this, but Lloyd — relying on skills from a lifetime of teaching — won’t let her.

This isn’t just the heart of the scene — it’s a pivotal scene in the film. It’s the moment when Maggie turns the corner and starts taking steps to be someone a little better…because she starts believing in her ability to see through to the core of things, and in the first-time-ever notion that she has a lot more to develop and uncover within herself.

I know how cliched it sounds to say a character “turns a corner” and so on, but sometimes these moments happen in life. You just have to be able to hear the little voice in the back of your head that says, “You’ve taken a small step…you’ve just moved along.”

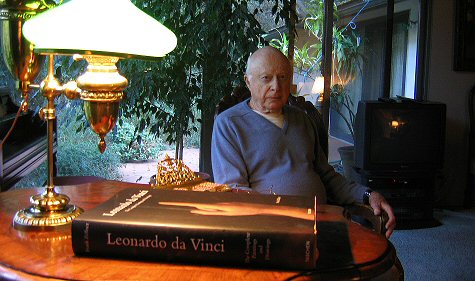

Norman Lloyd in his living room of his Brentwood home — Tuesday, 9.27, 5:45 pm.

I said Lloyd was in three scenes — he’s really in five.

There’s a brief scene near the end in which Diaz and Lloyd’s grandson — a doctor — talk about him and then how Lloyd has spoken about her. Lloyd is “there,” so to speak, and like Bishop’s poem, the subtext is loss.

In the film’s final minutes Diaz reads another poem — this one by e.e. cummings — and this time with more confidence and feeling. And Lloyd is there again.

It’s funny, but I feel as if I’ve known Lloyd all my life via his performance in Alfred Hitchcock‘s Saboteur, and now, in my mind (and everyone else’s, I’ll bet, once the film opens), he’s back again and on the map.

I’m not going into some Hollywood journalist suck-up routine when I say Lloyd ought to be handed a Best Supporting Actor nomination. He’s really earned it. It’s hard enough to make an impact like this with a fully-rounded part, but with only one scene to work with…well.

I called him yesterday morning and did a quick interview, and then I drove over to his place in Brentwood that afternoon to snap a couple of photos.

I want to be just like Norman Lloyd when I’m almost 91. He’s done everything, been everywhere and knows (or knew) everyone. And he’s healthy and spirited with the intellectual vigor of a well-educated 37 year-old.

Lloyd has been acting since the `30s and producing since the `50s. He’s been directed on-stage by Orson Welles (in “Julius Caesar” and “Shoemaker’s Holiday”) and Elia Kazan, and on film by Hitchcock twice (Spellbound was the other film), and Jean Renoir (The Southerner), Charlie Chaplin (Limelight), Peter Weir (Dead Poet’s Society) and Martin Scorsese (The Age of Innocence).

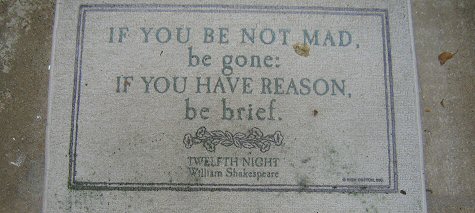

He lives on a quiet sycamore-lined street in a beautiful ranch-style home, in front of which horses go clop-clopping by in the late afternoon. He was born in New Jersey and grew up talking like one of the Dead End kids, but since the ’30s he’s spoken with a refined mid-Atlantic accent (learned at the hand of acting teacher Eva Le Gallienne). He drives a beautiful black Jaguar and has a doormat with a quote from Shakespeare’s “Twelfth Night.”

And he plays tennis well enough to have competed two months ago in the finals of the DGA tennis tournament. (His doubles partner is 45 years younger.)

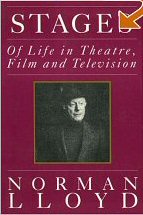

Last year Limelight Editions published Lloyd’s autobiography called “Stages: Of Life in Theatre, Film and Television.”

He was told about the In Her Shoes part by his agent, Merritt Blake, and went down to meet with Hanson and producer Carol Fenolen.

Lloyd (lower left) and Robert Cummings during finale in Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur

“I don’t ‘read’ for parts,” says Lloyd. “I myself have produced a great deal. I was one of Alfred Hitchcock’s producers on his TV show in the `50s, and I know that a radio actor back in the 1930s could read marvellously well on an audition because he was trained to read quickly, whereas other actors who might have been better in the long run sometimes couldn’t read as well.

“Anyway, my point is that at the end of our conversation Curtis said, `You have worked with the greatest directors in the history of this business’…which is true. And that was the extent of our meeting. I was told I had the part the next day.”

I told Lloyd I thought his performance was enhanced — intensified — by the fact that his character’s sightless eyes are always trained on the ceiling when he speaks with Diaz.

“You have uttered an amazing truth about acting,” he replied. “It is a wonderful thing when you’re acting and you eliminate one sense…sight, hearing, something. It makes it more powerful. I didn’t play the character as a sick man. To be without sight added to the voice, to the presence.”

His scenes with Diaz were shot over two or three days in a hospital in Arcadia. Like many of his generation he takes a straightforward approach to acting. His motto is “just say the words.”

There’s a beautiful drawing of Lloyd’s wife Peggy on the living room wall near his front door. The artist is Don Bachardy, and it was drawn 32 years ago…just as Lloyd’s wife had learned of the death of Pablo Picasso, whom she deeply admired and which accounts, he says, for her sad expression.

“My wife is 92,” Lloyd confides. “We’ve been married 69 years, and she tells everyone she robbed the cradle.”

What’s Lloyd been doing all these years to have lived so long and still be so alert and in such good shape?

“I eat a steak or two every week, although I don’t make a steady diet of that,” he replies. “No shellfish. I gave up smoking in 1943. I’ve played tennis all my life. For years I rode a bicycle here but with the traffic and everything I’ve given that up.

“The positive thing is that I was young in the Depression era, and the Depression people had more of a positive attitude about things. Now there’s a cynical thing in the air…I don’t see that same positiveness.”

Lloyd wrote an afterword to a 2004 Signet Classics Penguin paperback that contains four Shaw plays….’Candida,’ ‘Mrs. Warren’s Profession,’ ‘Arms and the Man’ and `Man and Superman.’ “I’m still tied in with Shaw,” he says, “although he did become bitter, like Mark Twain, about the human race.”

Cameron Diaz, Norman Lloyd at In Her Shoes post-premiere party at Spago of Beverly Hills — Wednesday, 9.28, 11:40 pm.

I was certain that Lloyd would be unusual and inquisitive enough to be an internet expert, but no. He is, however, a “careful” newspaper reader. As a favor I agreed to print out a copy of this column and give it to him at Wednesday night’s (9.28) In Her Shoes after-party.

Does he ever get recognized in public? “Of late not so much,” he says. “I was recognized in the `40s after Saboteur came out, and in the ’80s occasionally because of my part in St. Elsewhere (i.e., “Dr. Auschlander”), which I did every week for six years.

“But just the other day I was in a Chinese restaurant — VIP Harbor Seafood at the corner of Wilshire and Barrington — and six guys from 20th Century Fox who had just seen the film…they all came over to congratulate.”