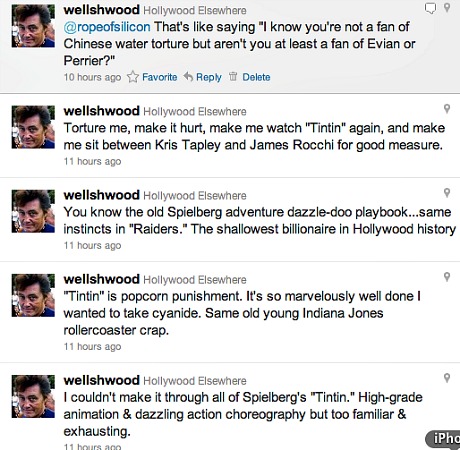

If you have a place in your moviegoing heart for an empty synthetic entertainment that will delight your inner nine-year-old, Steven Spielberg‘s Tintin will rush in and twinkle your toes. A motion-capture adventure thriller in the vein of Raiders of the Lost Ark and the four Pirates of the Caribbean films, it showed last night at the Chinese, and I almost made it to the end. I just couldn’t stand all that technical skill and pizazz and exactitude in the service of absolutely nothing, you see. It was just too much of a rousing, highly disciplined, relentlessly energetic kids movie for me to take, given my personality and tolerance levels.

All I know is that I never, ever want to sit through Tintin again. Because, as I said last night, it is popcorn punishment. I felt like I was being whoopee-cushioned and thrill-ridden to death, or like a virus was being injected into my system. Such amazing filmmaking, and it was making me sick.

As with all Spielberg films, which are always superficially diverting without the slightest hint of subtext, Tintin is about nothing but light and colorful characters and swirling camera movement and high adrenaline and technology. It is about Spielberg wanting to excite easily excitable minds and sell tickets and popcorn and make himself and producing partner Peter Jackson a little bit richer.

Did I say it was utterly without context? That’s not entirely true. Tintin‘s second-billed character, after Jamie Bell‘s Tintin, is Andy Serkis‘s Captain Haddock, who is fond of spirits. This is a minor side issue, I realize, but the fact that Bell’s Tintin seems to regard Haddock’s boozing as a tolerable eccentricity is, of course, a reflection of Spielberg’s attitude about same, which strikes me as curiously divorced from our 2011 reality.

In the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, supporting characters with alcohol problems (Walter Brennan‘s seagoing rummy in To Have and Have Not, Arthur O’Connell‘s boozy attorney in Anatomy of a Murder, Edmond O’Brien‘s alcoholic Senator in Seven Days in May) were often portrayed as marginally charming and, oddly, men of character. They needed to cut down on the drinking, of course, but they were loyal and colorful and fun to have around. In today’s social context this would be a misguided or pathetic attitude, to put it mildly, which is why the last truly entertaining drunk — Dudley Moore‘s Arthur — came along 30 years ago. But Spielberg is oblivious to this.

Why am I even talking about alcohol issues? Spielbergland is Neverland. I’m wasting my time.