Unlike the recently released Wizard of Oz Blu-ray super-package, the North by Northwest Blu-ray (which just arrived via FedEx a half-hour ago) doesn’t come with goodie knick-knacks. It’s just a disc in a hard cardboard case with a nicely written and illustrated booklet. And no, I haven’t popped it in yet.

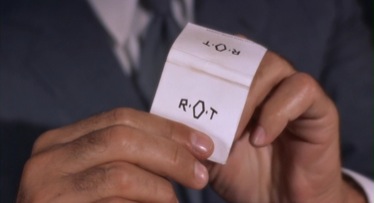

But if goodie knick-knacks had been part of the package, it would have been great to find that white matchbook with R.O.T. — the initials of Cary Grant‘s advertising executive Roger O. Thornhill — printed on the cover. (Robin Wood‘s brilliant but very literal-minded essay on North by Northwest, included in Hitchcock’s Films, contends that R.O.T. is also an arch metaphor for Thornhilll’s spiritual state as the film begins.) That I would have treasured. That I would pay for.

Here, by the way, is an amusingly touched political essay by Rob Giampietro comparing North by Northwest with The Limey.

“Some of the most heated debates of the ’60s/New Wave were Marxist-Capitalist debates,” it begins, “but in these two films Alfred Hitchcock and Steven Soderbergh actually visualize these opposing ideologies by consistently placing them in formal opposition to one another and moving their characters between them.

“North by Northwest, made in 1959, came at a cusp point of the Atomic Age amidst the post-WWII prosperity in America, and its finale, in which both Communism is thwarted (though it’s not said outright) and a marrage is made, reckons with these twin late-’50s predicaments. The Limey, made in 1999, came after the end of the Cold War and amidst a wave dot-com prosperity in America. That the Marxist is a villain in one and a hero in the other speaks volumes about these thrillers. That both films are thrillers helps determine exactly how.”

Wait…Terrence Stamp plays a Marxist in The Limey? Oh, right — that line he says about “at one time I was into re-distributing wealth.”

“Again and again, Soderbergh and Hitchcock use the idea of exchange over time, and, more importantly, over space to discuss Marxist and Capitalist ideologies. By coupling movement — which is concerned with the formal kinetics of the characters, camera, and shots — with ideology — which is concerned with the social implications of the films’ content — both directors formulate a relationship between the way things move on screen and what they ideologically represent.”