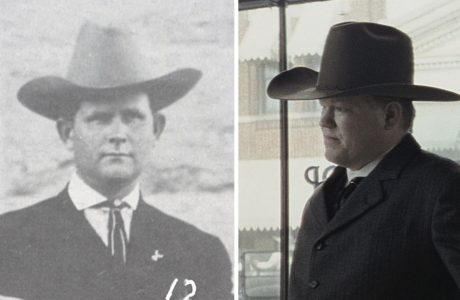

On the night that Unforgiven won the Best Picture Oscar, which happened on 3.29.93, none of us had the slightest inkling that roughly two decades into the 21st Century (or 30 years hence) corporate Hollywood would be operating under the adhere-or-die principles of China’s Great Cultural Revolution, and that films that reflected the creative vistas, mindsets and inclinations of the dudes who were pretty much running things back in the early Clinton era would be all but suffocated.

Which isn’t to say that the moral, administrative and attitudinal changes brought about by wokester commandants starting around five or six years ago (post-Moonlight and post George Floyd BLM-ers, LGBTQ-ers, #MeToo) didn’t transform the Hollywood industry into a much more fair, just and humane thing. They did. These changes also ensured, however, that the kind of urgent, occasionally irreverent and sometimes super-bull’s-eye films that occasionally poked through between 1930 and 2015…those kind of films would, for the most part, never again be made for theatrical.

Because the Hollywood Maoist system (“Don’t offend Zoomers or Millennials!…don’t wink at or even acknowledge outmoded attitudes!…don’t allow any representations of the way life was on the planet earth before woke-ism came along…all casts must prominently feature women, actors of color and LGBTQs”) has largely outlawed this approach or aesthetic.

Herewith a true story from a critic friend, edited by the author so as to obscure his/her identity, that is very, very slightly about Unforgiven:

“I know it’s wrong to speak ill of the dead (i.e., Richard Donner). But I so enjoy telling this story.

“I’ll start with this: Any job description in a help-wanted ad seeking to hire a critic should include these words: “Must be a bit of a dick.”

“The ads never say that. But they should. Because, no matter how nicely you do it, some people don’t take criticism well. Inevitably, you will have to say something negative in a public forum about the creative expression of another human being. Whether you mean to be or not, they’ll think you’re a dick.

“Here’s the thing: Sometimes, it’s really enjoyable to be as witty and as nasty as you can when you’re writing a review. Because being a dick is, by definition, fun.

“I knew early on that I had the ability to provoke and the willingness to do so (along with a shocking inability to foresee possible consequences of my actions). I take a certain pride in a well-turned phrase and an irreverent sense of humor.

“But while I’d experienced the immediate reactions of local artists — actors, directors, musicians — to my reviews in the early years of my career, I’d rarely had the sense that, when I wrote a movie review or a review of a rock concert, the people I was writing about ever actually saw what I wrote.

“Which brings me to my point about being a dick, and my Richard Donner story.

“In 1994, during a moment when there was a microburst of interest in westerns because of the success of Unforgiven and Dances With Wolves, I’d been assigned one of those trend stories that editors love: the return of the Western. So I started making calls.

“One of those went to a publicist at Warner Bros., which was a few months away from releasing Richard Donner‘s remake of the 1950s TV hit, Maverick, starring Mel Gibson, Jodie Foster ands James Garner. Could I get a few minutes on the phone with Donner, I asked, to talk about westerns?”

[HE interjection: I wrote at the time that Maverick was “a $75 million dollar Elvis Presley film” — a line that I stole from an attorney friend.]

“Donner was a director and producer of commercially successful middlebrow (or worse) films starting in the 1960s, including Superman with Christopher Reeve, The Goonies (most overrated kids film of all time), The Omen and the Lethal Weapon films, which, to my mind, had ruined action movies.

“In those days before cell phones and e-mail, the reply came with surprising swiftness. I got a call back the same day from the Warners’ publicist, telling me, no, Richard Donner would not speak to me about westerns — or anything else, apparently.

“‘Why not?’ I asked.

“‘Did you write a review of his film Radio Flyer‘, the publicist asked.

“It had been two years, but I knew exactly what he was talking about: I believe I called it ‘a feel-good film about child abuse.’

“‘Yeah, well, that was apparently a very personal film for him, so he’s not going to talk to you,’ the publicist said.

“Until that point — 1994, in a career that started officially when I turned pro in 1973 — I had no sense of anyone reading my reviews other than the

people within the immediate circulation area of my newspaper. I forwarded them to the film publicists in New York, and knew they were syndicated.

But I simply didn’t imagine filmmakers themselves actually taking the time.

“Now, however, I knew I had Richard Donner’s attention.

“So when Maverick came out in 1994 and I reviewed it, I referred to him on first reference as “Richard Donner, who directed Radio Flyer, a feel-good film about child abuse.”

“I did the same when he released Assassins in 1995: “Richard Donner, who directed Radio Flyer, a feel-good film about child abuse…” And

when he released Conspiracy Theory in 1997. And Lethal Weapon 4 in 1998: “Richard Donner, who directed Radio Flyer, a feel-good film about child abuse…”

“It was my own little inside joke, poking an obviously sensitive area with a sharp stick. Was he getting the message? I could only hope. Because Donner only directed a movie every year or so (while I was reviewing upwards of five movies a week), none of the editors I worked for ever noticed that I was repeating the joke. There was enough turnover among copy editors that it was greeted as a fresh line each time I deployed it.

“Am I proud of this bit of childishness? Obviously it’s a total dick move, but yes, the devilish part of me delighted in it.

“And there was also this: Richard Donner was an extremely rich Hollywood filmmaker who surely received plenty of bad reviews in his life, because he made a lot of terrible (if popular) films — and because I wrote a lot of those bad reviews. The difference here was that he couldn’t rise above his hurt feelings over a snotty review to talk to me for my story, where he could use the conversation to ask me directly about what I wrote about his film.

“And I do love the needle. There’s a saying in my family, which I coined after a joke at the expense of one of my then-teen-aged sons: ‘Do you know how I know that was funny? Because I’m laughing.’

“That would be the end of the story except that, in 2003, Donner directed an awful film version of a middling Michael Crichton time-travel novel called Timeline. I went to an early screening at the Paramount screening room in Manhattan and, when I arrived, found a cocktail reception in full swing, apparently for the critics in attendance. (Refreshments weren’t normally served at screenings. If they were, the line of shnorers would have stretched around the block.) I got a drink and found a Paramount publicist to ask what the occasion was.

“‘Oh,’ she said brightly, ‘Richard is here and wanted to meet everyone.’

“I almost did a spit-take and tried to stifle a whoop of laughter.

“‘What’s so funny?’ The publicist gave me a puzzled look.

“‘I’ll call you tomorrow and tell you,’ I said, because, at that point, another publicist swooped into the screening-room lobby with Richard Donner in tow. We were quickly lined up, as though we were about to be inspected by the queen. Except, instead of the queen, it was Richard Donner.

“He worked his way down the line, pausing long enough for each of us to be introduced to him and shake his hand.

“‘…and this is Rufuas T. Gobbledygook from the X Syndicate,’ the publicist said when they stopped in front of me.

“I looked Donner squarely in the eye and smiled broadly as I grabbed his hand quickly and shook it energetically: ‘Nice to meet you.’

“As our hands made contact, he registered my name like a slap. By that time, I was already pumping his hand. I let go before he had a chance to recoil and he was ushered along to the critic next to me, as though nothing unusual had occurred.

“Then we all went inside and watched the movie, leaving Donner in the lobby. He was gone when the movie let out.

“The next morning, the publicist called me almost before I had my coat off at the office: ‘What did you do to Richard Donner last night?’

“‘Shook his hand. Why?’

“‘After you critics went in, he came over, very agitated, and said, ‘That was Rufus T. Gobbledygook? What is he doing here? He’s a baaaad guy. What did you do?’

“The same thing, it turned out, that I did when I wrote my review of that film. The review began, ‘Timeline is directed by Richard Donner, who made Radio Flyer, a feel-good film about child abuse…’

“What can I say? I’m a dick. With a long memory.”