Last weekend I sat for my second viewing of Julian Schnabel‘s At Eternity’ Gate (CBS Films), which I’ve come to regard, no lie, as the finest Vincent Van Gogh flick ever made.

The difference between it and, say, Vincent Minnelli and Kirk Douglas‘s Lust for Life or Robert Altman‘s Vincent and Theo is a gentle but absolute communion with Van Gogh’s inner light. It’s not a tourist’s view of the man, but a portrait of an artist by an artist — a “you are Van Gogh” dreamscape flick.

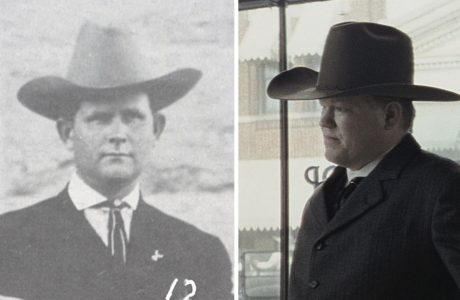

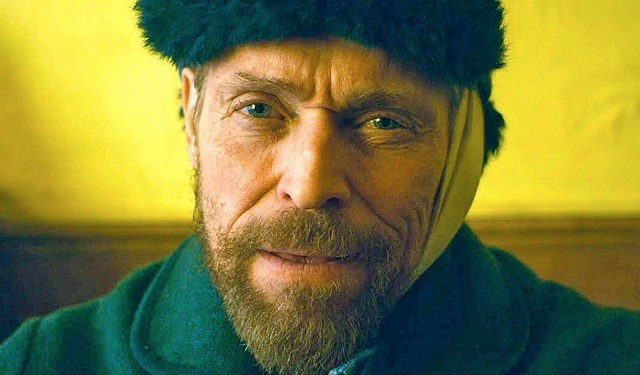

In the view of many Willem Dafoe‘s performance of this gentle, conflicted, angst-ridden impressionist is his best since playing Yeshua of Nazareth in Martin Scorsese‘s The Last Temptation of Christ (’88).

When I say “many” I mean the National Society of Film Critics, who yesterday morning celebrated Dafoe’s performance as a top-tier achievement. That’s quite the ringing endorsement when you think of the competition. Dafoe’s Van Gogh also won the Volpi Cup for Best Actor at the Venice Film festival, and he’s currently nominated for Best Actor prizes with the Broadcast Film Critics Association (i.e., Critics Choice), Alliance of Women Film Journalists and the San Francisco and Toronto Film Critics associations.

Let no one forget that Dafoe is a three-time Oscar nominee for his performances in Oliver Stone‘s Platoon (Sgt. Elias), E. Elias Merhige’s Shadow of the Vampire (Max Schreck) and Sean Baker‘s The Florida Project (the hapless Bobby Hicks).

From Manohla Dargis‘s N.Y. Times review of Schnabel’s film: “Few actors can look so frightening or so beatific in such rapid succession. Dafoe’s thin, coiled physicality suggests both fragility and determination, while his tensile face flutters with an astonishment of emotions that, by turns, suggest a yielding or off-putting sensibility. [And] Vincent’s agonies render moot the age difference between the character and actor; Dafoe is 63, and his deepest creases can seem like evidence of Vincent’s current and past suffering.”

At Eternity’s Gate is essentially a channelling of the dreams and torments that surged within Van Gogh during the final chapter in his life, when he lived in Arles and St. Remy de Provence. The film is more into communion than visions — intuitions, intimacy, revelations.

“Rather than a movie about Van Gogh, I wanted to make a film in which you are Van Gogh,” Schnabel said during a NY Film Festival presser that I attended.

The best scene in the film, I feel, is one in which Van Gogh, temporarily incarcerated in a mental asylum, has a somewhat testy conversation with a doubting priest (Mads Mikkelsen). The priest is softly contemptuous, saying in so many words that he thinks Van Gogh’s paintings simply aren’t very good, and that he’s almost certainly deluding himself by thinking that God meant him to pick up a brush.

Van Gogh responds just as softly that he might be painting for people who haven’t been born yet (or words to that effect). The instant Dafoe said this some guy sitting behind me went “uhn-huh” and I muttered the same thing to myself — “That’s right…that’s exactly what he’s doing.”

I know the Van Gogh territory to some extent. I’ve been to Arles. I’ve stood inches away from some of Van Gogh’s paintings at the Musee D’Orsay. Time and again I’ve stood near the doorway of the Montmartre apartment building that Vincent and Theo shared in 1886 or thereabouts. I saw Vincente Minnelli‘s Lust for Life when I was 15 or thereabouts, and it never left me. All my life I’ve been on the Van Gogh ride, all the way, many decades, deep down. If you ask me Schnabel and Dafoe have totally nailed it.

You can’t say you’ve really sunk into the best-of-2018 realm without seeing and celebrating Dafoe’s performance. You can’t not go there.