I mentioned two days ago what a nervy, exacting and well-sculpted film Margot at the Wedding (Paramount Vantage, 11.16) is, and that Noah Baumbach‘s direction and writing, at the very least, deserve respect for having produced the gnarliest ensemble piece of the 21st Century.

I was taken, in other words, by the boldness in making a film about a family reunion that is so startlingly cold and strange and unconcerned with audience engagement.

There’s plenty of time to get into this down the road, but I saw Margot at the Toronto Film Festival, and I don’t want to imply a derisive or dismissive attitude by being silent. I didn’t “like” it very much, but at no point did I feel I was watching a meltdown or a car wreck. It’s a very well condensed, carefully layered study of some very screwed-up people. It just doesn’t care to tell a story that provides “answers” or any sort of parting of the clouds, or what most of us would consider a sufficient number of laughs.

If for no other reason, Margot is worth grappling with because of Baumbach’s one master stroke, which was to have the the film embody or emulate the deranged self-absorption of the characters.

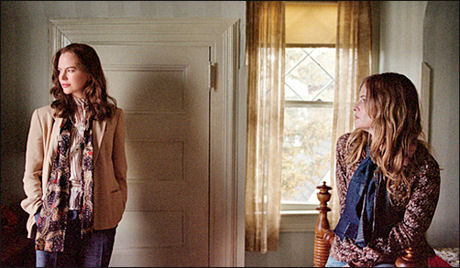

The principal nutters are played by Nicole Kidman, Jennifer Jason Leigh and Jack Black, but every character in the film (except for Kidman’s androgynous son, whose name escapes, and her ex-husband, played by John Turturro) would have been thrown into Bedlam if they’d lived in London of the mid 1800s.

As we soon discover in this warped family get-together piece, nobody gives a damn about anything except for the fickle meditations swirling around in their heads, and Baumbach doesn’t give a damn about anything either (certainly not the reactions likely to be shared by average viewers).

What is the most hateful, go-away quality that anyone can possess aside from being a serial killer or having lethal gas or halitosis issues or lacking the ability to control your bowels? Manic self-obsession, or the inability to pay the slightest attention to the thoughts, feelings and needs of others.

This is the affliction that permeates Margot at the Wedding. Some have said it cripples it, but I disagree. Baumbach’s commitment to this mental-emotional state in his characters is so rapt and uncompromised that it’s almost thrilling. “Almost,” I say. You certainly can’t say Margot at the Wedding isn’t hard-core.

Imagine a modern Chekhov play peopled by an assortment of Hannibal Lecters without the cannibalism, the wit and the lacerating insights.

Margot‘s/Baumbach’s only two flaws are (a) not dealing satisfactorily with those ghastly pig-butchering neighbors who live on the other side of the fence in a ramshackle house, and (b) being cavalier about the cutting down of a large family tree that borders the two properties.

Trees are holy, sacred things — especially big ones — and should only be cut down if safety absolutely requires it. The pig-butchers want it taken down because of a root problem in their yard, but this is never really disputed (not vigorously) or explored, and before you know it Black is cutting a pie into the main trunk with a chain saw, and he doesn’t know how. For a tree-lover like myself it was like watching him suffocate a family dog or cat with a pillow.

I used to be a tree surgeon, and there’s a way to take a tree down. You climb up to the top, tie in, and drop down to the lowest level of leaders or branches and start sawing them off, one by one, as you work your way up. The idea is to create a branch-less totem pole, which you then drop onto the “bed” you’ve made of leaders and branches. In the film Black just drops the whole thing on top of a wedding tent — an act that temporarily symbolizes an end to his forthcoming wedding to Leigh.

I’ll re-examine this film four or five weeks from now. It’s partly infuriating, but it’s never uninteresting. I’d like to see it again and think it through some more.