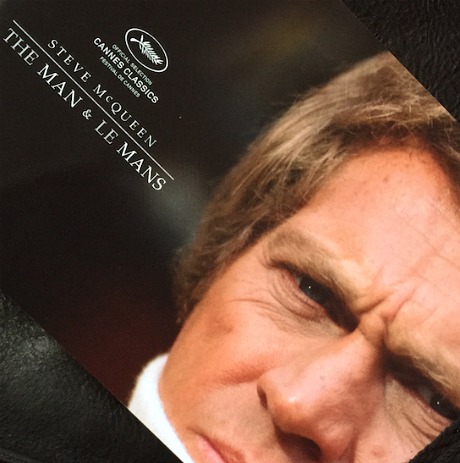

Yesterday afternoon I caught Gabriel Clarke & John McKenna‘s Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans — in part a fascinating time trip but mostly a sad, bittersweet mood piece about failure and a movie star swallowing his own tail. Which I found affecting as hell. Clarke and McKenna have certainly made something that’s heads and shoulders above what you usually get from this kind of inside-Hollywood documentary. Heretofore unshared insight, a lamenting tone, an emotional arc. Plus loads of never-seen-before footage (behind-the-camera stuff, unused outtakes) plus first-hand recollections and audio recordings. A trove.

Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans may seem at first glance like a standard nostalgia piece about the making of McQueen’s 1971 race-car pic, which flopped critically and commercially. (I own the Bluray but I’ve barely watched it — the racing footage is authentic but the movie underwhelms.) Yes, in some ways the doc feels like one of those DVD/Bluray “making of” supplements, but it soon becomes evident that Clarke and McKenna are up to something more ambitious.

What their film is about, in fact, is the deflating of McQueen the ’60s superstar — about the spiritual drainage caused by the argumentative, chaotic shoot during the summer and early fall of ’70, and by McQueen’s stubborn determination to make a classic race-car movie that didn’t resort to the usual Hollywood tropes, and how this creative tunnel-vision led to the rupturing of relationships both personal (his wife Neile) and professional (McQueen’s producing partner Robert Relyea, director John Sturges), and how McQueen was never quite the same zeitgeist-defining hotshot in its wake.

There were two basic, insurmountable problems during the shooting of Le Mans, and both were on McQueen.

One, he was determined to make the most authentic race-car movie of all time, and to him that meant not tricking it up with the usual Hollywood-style plot elements, like a love story or even for that matter a dramatic structure. So he nixed all attempts at cobbling together a movie that would deliver the usual beats or connect emotionally with Average Joes. And two, he was so powerful in those days that nobody could tell him what to do, and that resulted in legendary helmer John Sturges (The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape) quitting in frustration, saying more or less that “I’m too old and too rich to put up with this horseshit” (or words very close to that).

And yet you have to give credit to McQueen for trying, at least, to make a movie that was really wowser and groundbreaking — a game-changer. “McQueen wasn’t Hercules,” a former colleague says. “He was Icarus, and he never quite understood the point at which the wax starts to melt.”

Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans is filled with witnesses who were there, who knew and loved him (including his son Chad McQueen), who admired or were at least charmed by him. The one problem I had with the doc is that while it leads you to conclude that McQueen was, in the usual manner of rich macho superstars, cocky and swaggering and listening only to the urges of his ego and his dick, not one talking head says this in so many words.

If just one ex-colleague or former friend had said something like “I loved Steve like a brother but he could be a selfish asshole at times, and he really topped himself during the filming of Le Mans…he really fucked himself royally,” it would be a cleaner film.

After Le Mans McQueen kept rolling and punching out good films, of course, but the juice had diminished. After the film crashed and burned something inside seemed to wilt. He began talking more and more about not doing this or that, about maybe retiring or doing something besides acting, etc. Which always seemed evident to me. I’ve always felt that McQueen’s peak years began with Hell Is For Heroes (’62) and ended with The Getaway (’73)…okay, The Towering Inferno (’74).

And then he came back a little bit at the very end with The Hunter and Tom Horn. And then he died in 1980, at age 50. From cancer brought on by abestos poisoning.