I’ve written a few times about the four different kinds of film scores — (a) old-school orchestral, strongly instructive (telling you what’s going on at almost every turn), (b) emotional but lullingly so, guiding and alerting and magically punctuating from time to time (like Franz Waxman‘s score for Sunset Boulevard), (c) watching the movie along with you, echoing your feelings and translating them into mood music (like Mychael Danna‘s score for Moneyball), and (d) so completely and harmoniously blended into the fabric of the film that you’ll have a hard time remembering a bridge or a bar after the film ends.

We all understand that the era of classic film scores — composed by Miklos Rosza, Bernard Herrman, Waxman, Max Steiner, Maurice Jarre, Alex North, Dimitri Tiomkin, Bronislau Kaper, Ennio Morricone, Leonard Rosenman, Nino Rota, Elmer Bernstein, Alfred Newman, Hugo Friedhofer and Jerry Goldsmith — is over and done with. Their work (i.e., the artful supplying of unmissable emotional undercurrents for mainstream, big-studio films that peaked between the mid 1930s and late ’70s) belongs to movie-score cultists now. It’s sad to contemplate how one day these awesome creations will be absent from playlists entirely.

But I’ve always enjoyed these movie symphonies the most because their composers — most of them classically trained and European-born — didn’t just write “scores” but created non-verbal, highly charged musical characters. They didn’t watch the film in the seat beside you or guide you along as most scores tend to do — they acted as a combination of a Greek musical chorus and a highly willful and assertive supporting character.

These “characters” had as much to say about the story and underlying themes as the director, producers, writers or actors. And sometimes more so. They didn’t musically fortify or underline the action — they were the action.

If the composers of these scores were allowed to share their true feelings they would confide the following before the film begins: “Not to take anything away from what the director, writers and actors are conveying but I, the composer, have my own passionate convictions about what this film is about, and you might want to give my input as much weight and consideration as anyone else’s. In fact, fuck those guys…half the time they don’t know what they’re doing but I always know…I’m always in command, always waist-deep and carried away by the current.”

Eight and a half years ago I wrote the following about Rosza in a piece called “Hungarian Genius“: “Rosza sometimes let his costume-epic scores become slightly over-heated, but when orgiastic, big-screen, reach-for-the-heavens emotion was called for, no one did it better. He may have been first and foremost a craftsman, but Rosza really had soul.

“Listen to the overture and main title music of King of Kings, and all kinds of haunting associations and recollections about the life of Yeshua and his New Testament teachings (or at the least, grandiose Hollywood movies about same) start swirling around in your head. And then watch Nicholas Ray’s stiff, strangely constipated film (which Rosza described in his autobiography as ‘nonsensical Biblical ghoulash’) and it’s obvious that Rosza came closer to capturing the spiritual essence of Christ’s story better than anyone else on the team (Ray, screenwriter Phillip Yordan, producer Samuel Bronston).”

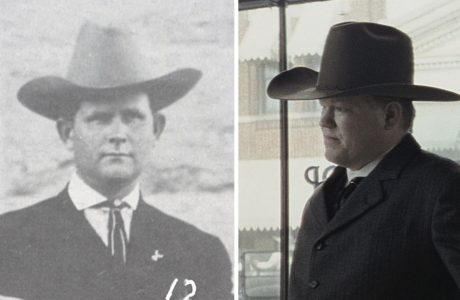

Why am I mentioning this observation? Because over the weekend I was re-watching the Criterion Bluray of One-Eyed Jacks, and I was enjoying the hell out of Hugo Freidhofer’s score. Talk about a strong supporting character! Freidhofer’s music is eyeball to eyeball with Marlon Brando as the film’s most dominant element.

Fragments: (a) “’Gently alerting’ is one way to describe Howard Shore‘s Spotlight score. It indicates that the movie is up to something solemn and real and worth your time. You hear a few bars and right away you’re saying to yourself, ‘Okay, there’s something going on here…I’m gonna focus because something of substance will probably come of it…I can just tell”;

(b) From a GQ piece by Joshua Rivera: “A lot of movie soundtracks aren’t so great right now. It’s surprising how many big blockbusters will be accompanied by scores that are hard to describe as anything other than ‘forgettable’. But what’s also interesting is that once-common musical ideas like motif have fallen out of fashion — when was the last time you saw a movie with a theme you could hum? The sort of instantly recognizable, heroic melody that has accompanied and elevated films like Rocky, or, hell, Star Wars, just doesn’t happen as often anymore, and in that way, Ludwig Goransson‘s Creed‘s score is kind of a throwback. But it’s a throwback that’s full of so much that’s new.”

(c) Ryuichi Sakamoto‘s sparely applied, solemn string music for Alejandro G. Inarritu‘s The Revenant, and Antonio Sanchez‘s all-percussion score for Birdman — both disqualified because their scores didn’t strictly adhere to the Academy rulebook.

(d) “I felt I’d come to know James Horner pretty well through his music over the years. Emotionally, I mean. The river within. His score for Phil Alden Robinson‘s Field of Dreams (’88) was the first Horner that really got me. I wrote last year that I think Horner’s score for Ron Howard‘s A Beautiful Mind was a significant reason why that film won the Best Picture Oscar. His scores for James Cameron‘s Avatar, Titanic and Aliens are legendary. The man was a maestro, a genius, a musical seer, one of the all-time greats.”

(e) “In a post-Golden Globes analysis piece (dated 1.12), Hollywood Reporter columnist Scott Feinberg states a general rule about musical scores, i.e., ‘The score you hear the most in a good film is usually the one that wins [awards].'”

(f) “Kenyon Hopkins‘ delicate musical score for 12 Angry Men creates a counterpoint mood to the film’s heated and acrimonious jury deliberations. It could be a score for a film about an elderly woman living in a musty old house with eight or nine cats and too much clutter. Stillness, solitude, lament. A portrait of who the jurors are within themselves, before and after the shouting.”

(g) “Franz Waxman‘s score is probably the single best element in Joshua Logan‘s Sayonara.”