I could sense trouble fairly early on in Wong Kar Wai’s My Blueberry Nights, a horribly written, woefully banal self- discovery mood piece (the word “drama” really can’t be applied) about a young girl (Nora Jones) who leaves her home town of Manhattan and starts job-hopping across the country — waitress gigs in Memphis and I-couldn’t-tell- what-town in Nevada, with an apparently uneventful stopover in Los Angeles — in order to get over a bad case of breakup grief.

That early “uh-oh” comes when Jones, playing a lady named Elizabeth with a certain doleful sincerity, is on the phone with her soon-to-be-ex. She asks him, “Are you seeing somebody else?” and then two seconds later she inquires “who is she?” In other words, the boyfriend (whose voice we don’t hear) has quickly admit- ted to infidelity. Of course, guys never admit there’s another woman without being hammered and prosecuted by their betrayed significant other for hours, if not days or weeks, on end. The male genetic code prohibits it. We all know this. So right away it’s obvious that the human behavior and particularly the human dialogue will not have the cast of reality.

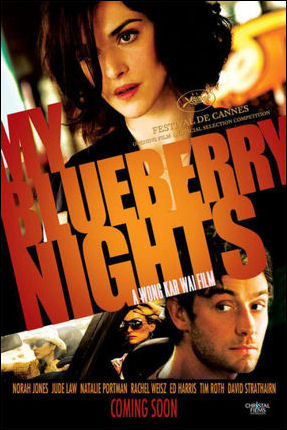

The Blueberry strategy, in any event, is roughly this: the folks whom Elizabeth gets to know and feel for during her episodic journey — a Manhattan pasty-shop owner from Manchester (Jude Law), an alcoholic, deeply depressed beat cop (David Straitharn), the cop’s hysterically alienated wife (Rachel Weisz), a hard- luck Nevada gambler (Natalie Portman) — are all nursing broken hearts, and their combined pathos somehow will prod Elizabeth into relinquishing the mope-a-dope and deciding to look forward and live in the now.

The “aha!” she finally absorbs seems to have something to do with realizing how much worse off everyone else is than she, along with the futility of letting hurt be the dominant chord. The problem is that there’s no giving a damn about any of it, particularly since Elizabeth’s new attitude leads her back to a possible relationship with the flirtatious Law, with whom she spends the first third of the film with, trading sad memories and little bon mots of bittersweet regret about bruised feelings and whatnot.

There’s just no investing in Law these days — every character he plays feels like a sly, gently calculating hound — and it’s impossible not to feel cynical about any female character in any movie hooking up with this smoothie because you know where it’ll all eventually end up.

Most of the “trouble” moments in My Blueberry Nights are rooted in the script by Wong and Lawrence Block. I can’t remember the last time that a film co-written by a major director was the cause of so much internal groaning. (I made no sounds during the screening although I did lean forward a lot, often with my hands covering my face.) There’s a lot of precious talk about abandoned apartment keys and blueberry pies, and way too many line that begin with the word “sometimes.” As in “sometimes the thing you’re running away from is the very thing that will save you. This line line isn’t literally spoken used in the film, but you get the idea.

Allusive wounded-heart dialogue has been woven into Wong’s films before, of course, but there’s a big difference between reading it via subtitles and hearing it spoken in English. All I can say is, the Blueberry dialogue is so bad that it makes the talk in Wim Wenders and Sam Shepard‘s Don’t Come Knockin’, which I saw and didn’t much care for in Cannes last year, seem much, much better in retrospect, and that’s saying something.

The only player who delivers any sense of scrappy believability is Portman, but even she can’t overcome the H.M.S.Titanic vibe flooding this thing. Strathairn is one of our very best character actors, and yet his portrayal of drunkenness here is painfully actor-ish. Weisz, working with a stagey Memphis drawl, is nearly as bad, and I never thought I’d say this about an actress as talented as she. They’re all sad pawns in this thing, having almost certainly agreed to appear in My Blueberry Nights on the strength of Wong Kar Wai’s exalted rep.

I don’t know which is worse — the whole waitressing-in-Memphis section of the film, or the endless soul-searching section with Law in the pastry shop. But put ’em together and wham, you’re looking at your watch and going “holy bejeezus, this is dreadful.” It’s time for Kar to say “okay, it didn’t work” and hightail it back to China. He doesn’t get America (he’s not the first foreign-born director to distinguish himself in this regard) and he sure as shit doesn’t get how people talk here. He was never obliged write or use “realistic” dialogue, of course, but every director has to be careful to use lines that don’t constantly defeat a skilled cast.

Even Darius Khondji‘s photography is irksome, or maybe the way Wong’s editing just makes it seem so. There are two or three shots of milk (or melted ice cream) cascading over a collapsed slice of blueberry pie, the heavy-handed allusion being semen making its way through a woman’s inner cavity. And there are several passages with “fake” slow motion, as if Wong only realized in post-production that he could give the film a more dreamllike quality with this technique.

The biggest howler comes when Jones goes into a Las Vegas hospital to ask whether Portman’s con-man father has died or has told a friend to pass along a message that he’s dead in order to get his daughter to pay a visit to a hospital he’s been staying in. Jones learns he’s actually left the earth from a couple of doctors. After describing what caused the dad’s demise, he tells Jones, “You should have come earlier.” Yes, she should have. That way she and Portman could have spoken with him because, you know, he wouldn’t have been dead.