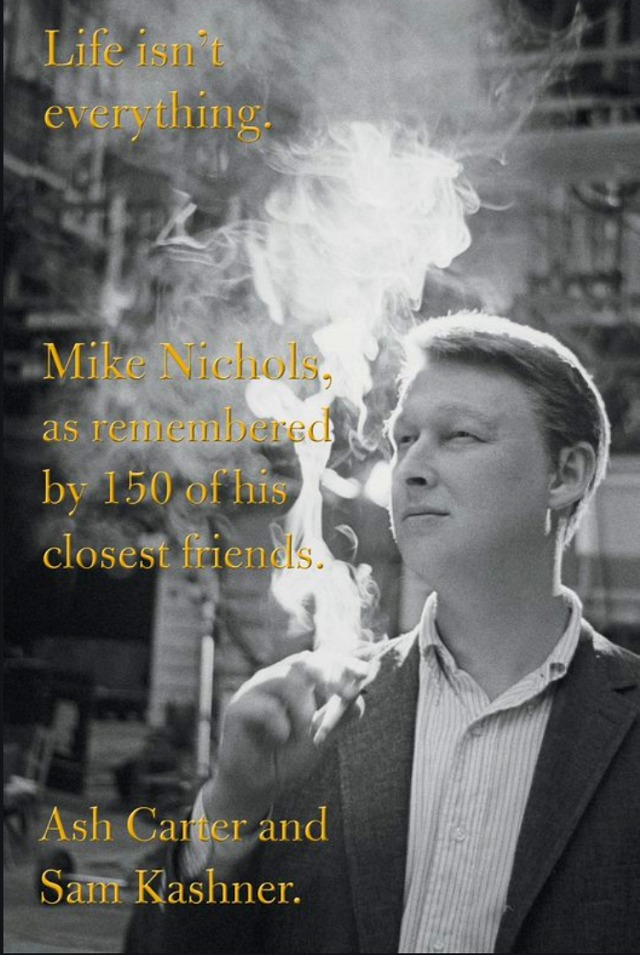

I’ve read three sample Kindle chapters of Ash Carter and Sam Kashner‘s “Life Isn’t Everything,” a strung-together oral history of Mike Nichols “by 150 of his closest friends.”

I’ll tell you right now that these portions — a prologue called “The Burton Stakes”, and the first two chapters, “Dybbuks and Golems” and “To Sell Another Drink” — feel too warm, too friendly, too alpha, too fond, too fraternal. There’s so much affection you can’t breathe.

Then again it includes a great snippet of a conversation between Nichols and Richard Burton, which happened sometime in the ’60s. Burton asked Nichols to look after Elizabeth Taylor in Rome. Nichols replied, “If it’ll help.” What Nichols meant, of course, is that nothing could ever help when it came to Ms. Sturm und drang. You had to weather it out or leave — there was no third option.

The basic drill is that no one disliked Nichols. No one found him irritating or frustrating or pompous. Some may have thought he was over-rated (I know one guy who insists Nichols’ only solid-gold films were Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf and The Graduate) but very few in the book share anything but astonishment and wonder at his miraculousness. They all feel blessed to have been in Nichols’ presence, however briefly. No one resented or felt sorry for him. No one wished he could’ve tried harder.

There’s no disputing Nichols’ charm, likability, sophistication, ease of manner — I sampled these things myself a couple of times. But the book (or at least the portions I’ve read) would have us believe that Nichols led something close to a charmed life. Failures, sure, but no major warts or crippling neuroses to speak of. Nichols had some tough times as a kid, but he managed to overcome or step around them, or shove them into a box.

It’s just a tiny bit boring to read over and over what a wise, fascinating, super-gifted guy Nichols was throughout the years and decades, even if he was all that.

Yes, he went into a downturn cycle in the ’70s. The Day of the Dolphin and The Fortune obviously speak for themselves. Nichols stopped making films and didn’t really get going again until 1983’s Silkwood, and when he re-emerged that static-long-take visual signature that he’d become known for (starting with The Graduate and ending with The Fortune) had disappeared, which struck some as unfortunate.

“Life Isn’t Everything” made me anticipate Mark Harris‘s forthcoming Nichols biography all the more, because at least his version (if I know Harris) won’t be entirely about how Nichols was always Mr. Wonderful.

For the third time, HE’s Nichols obit, initially posted after his death on 11.19.14 and then re-posted last year.