Obsessions

It’s said to be a problem when gifted filmmakers (and only the gifted fall prey to this) get caught up in the jib-jab of their brushstrokes and lose sight of the painting.

You know what I mean…movies that always seem to be emphasizing how hip and clever the director is, or how vast and ambitious his/her efforts were. There are more of these films in mainstream theatres toward the end of the year, naturally.

I love brushstrokes for their own sake. I can be half-sold on an entire film if there’s an exceptional contribution or two (photography, music, a performance). I’m not saying that excessive brushstroking isn’t distracting. I’m saying I find it easy to segregate my enjoyment of particular elements that work, even if the overall fails.

I just saw a movie that I can’t talk about yet, but I loved the main title sequence plus the dialogue in an epilogue scene at the very end. I will always feel warmly about this film for these two ingredients, regardless of any followup judgements I may render.

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

The reigning example of this syndrome, according to what nearly everyone is saying, is Robert Zemeckis’ The Polar Express (Warner Bros., playing everywhere). The rap is that this $165 million feel-good Christmas movie has invested more heavily in digital performance-capture technology than in the story-telling, character-building aspects, let alone the imaginative fun so abundant in The Incredibles.

It’s being said in some quarters that Wes Anderson’s The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (Disney, 12.25) is caught up in cleverness and style issues here and there. To what degree I can’t say, but a Wes Anderson film without style issues wouldn’t be a Wes Anderson film. I totally worshipped those live, non-digital, opening-curtain shots he used to begin each chapter of Rushmore.

Jean Pierre Jeunet’s A Very Long Engagement has a fair amount of stylistic archness, but so did Amelie and Delicatessen. A friend who thinks it’s a great banquet of a movie wrote a day or two ago asking why there isn’t more buzz about it. “[Jeunet’s] direction is stylish and exquisite, the production design is A-plus…is it because it’s French?” A certain know-it-all says the lack of excitement is over brushstroke issues.

There’s a certain self-referencing cleverness all through I Heart Huckabees, but like all credentialed art it’s steady and consistent, like the frenzied brushstrokes of Vincent Van Gogh. It’s all of a piece and I don’t care if it’s only made $10 million so far. This is one of those films that gets better and better the more you think about it, and one that absolutely improves if you see it a second time.

But the clever-dick aspects in Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind have always bothered me. I actually started to hate it because of this, despite my admiration for Charlie Kaufman’s script. It underlined my belief that when it comes to filming a Kaufman, Spike Jonze = good and Michel Gondry = less so.

Any other films that have bothered anyone for these reasons?

All Alone

I usually send these queries out by e-mail, but I’ll just plop this in. I was talking to a critic friend last night about the number of times he’s championed films that almost everyone else has hated. He had a fairly long list to recite from.

I don’t think a critic is worth much unless he/she experiences at least an occasional stand-alone episode. TV critics almost never do, and guys like Armand White and Jonathan Rosenbaum have these episodes every other week.

I remember admiring the crap out of Eric Blakeney’s Gun Shy, an early 2000 release with Liam Neeson, Oliver Platt and Sandra Bullock (and which Bullock helped to produce). Almost no one except New York Times critic Elvis Mitchell agreed.

It’s hard to get critics to admit to these episodes, but I’ll bet there are plenty of great stories to be told about what it felt like to stand all alone in the cold stiff wind with everyone (including your editor) looking at you like something’s gone seriously wrong because you stood up and led the charge for the “wrong” film.

If anyone wants to send in a recollection…

Down to This

There’s all this stuff happening in the Best Picture race suddenly. This film ascending, that film dropping out. And now our friend David Poland at Movie City News is saying “the only movie that can keep The Phantom of The Opera from winning Best Picture is The Aviator.”

No comment as I haven’t seen either film, but good God. Bush wins the election and now this. I’m just not a fan of any “lush, glitzy, over-the-top, overwrought” musical, which is how a friend has described Phantom. Is my friend the bringer of the last and final word on this Joel Schumacher film? No, and I could wind up liking it. It’s possible…but I don’t especially want to.

I keep hitting on this same point, which is that bigger and more grandiose and more thundering films are…aaah, forget it.

There’s no point. No point saying Sideways has it all because people keep saying nope, it’s not enough. It’s not enough to be insightful, adult, touching, funny, heartbreaking, emotional, soulful…and to be about average people living recognizable lives. No, cries the mob…we need more.

Poland emphasized in his Phantom prediction that this “is not about what I like.” For what it’s worth, he agrees with me about Sideways.

Best Picture Oscars are about emotion. The ones that deliver an emotional sandwich you can sink your teeth into and get a little choked up over or, failing that, say something simple but profound about life, something we all recognize as perceptive and truthful — these are the ones that tend to win it.

Why, then, did the awful Chicago win it two years ago? What did that film actually say? That we’re all users, abusers and bamboozlers, and that’s what makes the world go’ round?

American Beauty was the last people-sized movie to win the Best Picture oscar, but it was serene at the finish and said something bedrocky about our day-to-day, which is that we don’t pay enough attention to the beauty around us.

Sideways doesn’t quite choke you up, but it comes close when Paul Giamatti listens to Virginia Madsen’s voice message near the finish. And the knock on her door that directly follows says volumes about the life force, positivism, hope, love and refusing to fold up your tent.

Of course, it’s only a small masterpiece. Nothing to put your chips on. Broad and breathless is always better.

Prick Up Your Ears

Paul Matwychuck of Edmonton, Alberta, was the first to correctly identify all three of Wednesday’s (11.10) sound clips.

Clip #1 is Ben Kinsley hammering at Ray Winstone in Jonathan Glazer’s Sexy Beast; (b) Clip #2 is Terrence Stamp speaking to John Hurt in Stephen Frears’ The Hit ; and (c) Clip #3 is the brilliant Oskar Werner presenting his case to an East German tribunal in The Spy Who Came in From The Cold.

Today’s Clip #1 is from an urban cop film (obviously); (b) Clip #2 has some ambient noise effects, but the dialogue is detectable; and (c) Clip #3 — my favorite — is from a film based on a play, if that’s any help.

I’ll post the winner in the column in next Wednesday’s column.

Radiant

The color and detail in the new Gone With the Wind DVD box set that hit stores last Tuesday is mouth-watering. It’s the ripest and most sharply focused version I’ve ever seen. It probably looks better than the version GWTW‘s producer David O. Selznick and director Victor Fleming knew. I’m not exaggerating.

Even the hardcore restoration master Robert Harris (Lawrence of Arabia, Vertigo, Spartacus), who’s always very tough when I ask him to size up this or that digital makeover, says this new Gone With the Wind is “perfect…absolutely perfect…the most beautiful rendition I’ve ever seen.”

I don’t have the time or space to get into the others merits of this four-disc set, released by Warner Home Video, but they’re plentiful, trust me.

The idea-guy behind this GWTW‘s new look is a Warner Bros. technology executive named Chris Cookson. Three years ago he came up with an idea called edge detection, which involved digitally scanning the three different film strips that Gone With the Wind‘s Technicolor cameras used to capture the red, blue and yellow elements in each scene. But there was always a very slight fuzzy element in prints if the three strips were not perfectly aligned.

“The realization was that if we could just get these things to align [more precisely], we’d find detail and information that’s always been there but never visible,” Cookson says on a disc #3 documentary called “Restoring a Classic.”

The people who wound up writing the software for this process, which is known as Ultra-Resolution, were image scientists Sharon and Karen Perlmutter of America Online. Warner Bros. Senior Systems Engineer Paul Klamer put the team together and made sure everyone was on the same page.

What they did with Gone With the Wind, says Klamer, “is like taking the walnut oil off the Rembrandt paintings.”

“Not only is it aligned at least as good as the film was when it was originally released,” says Warner Bros. senior vp of production technology Rob Hummel, “[but] we believe we’ve probably achieved a level of alignment and registration that probably has never seen before.

“The result is actually beyond what we had hoped to see,” says Cookson. “A degree of detail that we didn’t even know to expect.”

Kool Aid

I’m running this excerpt from Manohla Dargis’s review of The Polar Express in the New York Times because I couldn’t agree more with what she says about the influence of George Lucas and other powerful tech-head types, and because she says it well.

“Directed by Robert Zemeckis, who wrote the film with William Broyles Jr., The Polar Express is a grave and disappointing failure, as much of imagination as of technology. Turning a book that takes a few minutes to read into a feature-length film presented a significant hurdle that the filmmakers were not able to clear.

“Animation is engaged in a debate that pits traditional and computer-assisted animation against computer-generated animation. The idea that anyone loves Finding Nemo because it was made wholly on a computer is absurd, but behind this debate lies a larger dispute not only about animation, but film’s relationship to the world as well.

“On one side of the divide are Pixar visionaries like [The Incredibles director] Brad Bird and the Finding Nemo co-director Andrew Stanton, who either know they can’t recreate real life or are uninterested in such mimicry, and so just do what animators have always done: they imaginatively interpret the world.

“On the other side of the divide are filmmakers like George Lucas who seem intent on dispensing with messy annoyances like human actors even while they meticulously create a vacuum-sealed simulacrum of the world.

“It’s worth noting that two important contributors to The Polar Express Doug Chiang, one of the production designers, and Ken Ralston, the film’s senior visual effects supervisor, worked for years at Mr. Lucas’s aptly named company, Industrial Light and Magic. There’s no way of knowing whether they drank the company Kool-Aid.

“Still, from the looks of The Polar Express it’s clear that, together with Mr. Zemeckis, this talented gang has on some fundamental level lost touch with the human aspect of film. Certainly they aren’t alone in the race to build marvelous new worlds from digital artifacts.

“But there’s something depressing and perhaps instructive about how in the attempt to create a new, never-before-seen tale about the wonderment of imagination these filmmakers have collectively lost sight of their own.”

Thunder of Hoofbeats

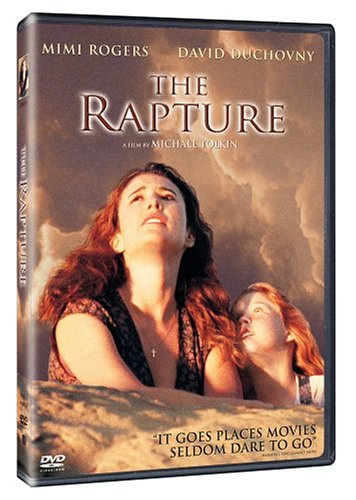

“Glad to see you mention The Rapture. I saw it when it was first released at an early screening in Atlanta that included an invitation-only audience of local churchgoers. Mimi Rogers and Michael Tolkin were there to take questions from the audience at the end of the movie.

“In the South, of course, the Rapture is just a given. It’s not uncommon to see cars with bumper stickers that read `In case of rapture, this car will be unoccupied.’ When I was in Junior High, the big book that everyone was reading was a tome about the rapture by Ernest Angsley (you remember him, he’s the televangelist/faith healer Robin Williams used to parody — “Say Baaa–by! Be HEALED!”).

“Almost everyone in the audience spoke of enjoying the movie and its “message” (presumably the depiction of the rapture) but complained of the excessive nudity during the opening sequences. No one spoke of the decision of Mimi Rogers’ character to kill her daughter and finally reject God’s salvation. Michael Tolkin tried to get people to talk about religion, but that sort of thing just isn’t done down here.” — Reed Barker, Peachtree City, Georgia.

“That’s a pretty cheap shot to take at Christians in your little piece about The Rapture. I’m sorry that your guy didn’t win the election, but let it go. Before you start saying that you’re afraid of Christians, you’d better do some serious reading. I certainly missed the Bible passage that states “shoot your child to send them to Heaven.”

“The Rapture is a movie, just like The Omen or The Exorcist. Are these films thrilling and entertaining? Sure. Do these films represent Christian doctrine? Absolutely not. Honestly, I feel sorry for you if you would let one film “push you into permanent atheism.” It one thing to say “I read the Bible and just don’t buy it”, but its another to say “I saw this movie, made by a guy who might have his own agenda, and now I know that Christians are all creepy.” That’s really objective.” — Jeff Horst.

Wells to Horst: I can’t think of the last time I’ve gotten to know anyone who answered to being a Christian. I guess it’s the circles I’ve travelled in over the last 20-plus years. But I’ve known a few, and I think they’re nice enough but also a bit creepy. And 90% of them seem to be righties. Every time I meet them, I think of that Dustin Hoffman line in Straw Dogs: “There’s has never been a kingdom given to so much blood as that of Christ.”

I reject with every gram of brain matter and every fibre of my being the notion that our time on earth is all about what happens to our souls after we pass on, and Michael Tolkin’s film just seemed to solidify these feelings, or ratchet them up a notch. The basic tenets of Christianity are a blessing to anyone who understands them and takes them into his or her heart, but I despise how Christianity has somehow become culturally aligned in this country with bedrock conservativism.

I just hate their uptightness and rigidity and aura of fearfulness…and that repugnant smugness they all seem to have about being plugged into and receving the world of our Lord Jesus, and always delivered with those gleaming eyes and awful toothy smiles. If I were a Roman Emperor and this was, say, 200 A.D., I’m not sure I would overturn the practice of throwing them to the lions in the Colisseum.”

Horst back to Wells: I understand the type of Christian that you’re talking about. If those are the people that you are citing, then you need to say that. Just saying `born-again Christians’ is painting with a really wide brush, and encompasses a lot of those people who really do try to live by those basic tenets that you referred to in your reply. It’s an important distinction.

“I hope its clear that I’m not saying that you have to believe in anything. That’s where well intentioned people usually go wrong. Everyone needs to believe in what they feel is right, as long as it doesn’t harm others. That’s supposed to be the whole point of this country that we are fortunate enough to live in.”

Originality

“In anticipation of their 2004 recaps, entertainment blurb writers everywhere are trying to suitably illustrate the sludge that Tom Hanks√¢‚Ǩ‚Ñ¢ star has slammed into — the worst Coen Brothers movie ever, one of Spielberg√¢‚Ǩ‚Ñ¢s poorest conceptions, and now maybe the all-time epic Christmas dud (with apologies to Ben Affleck). Please, blurb writers — try and come up with something better than √¢‚Ǩ≈ìHanks Express Derailed: 3 Audience Killers leaves fan base looking Terminal.” — Mark Frenden