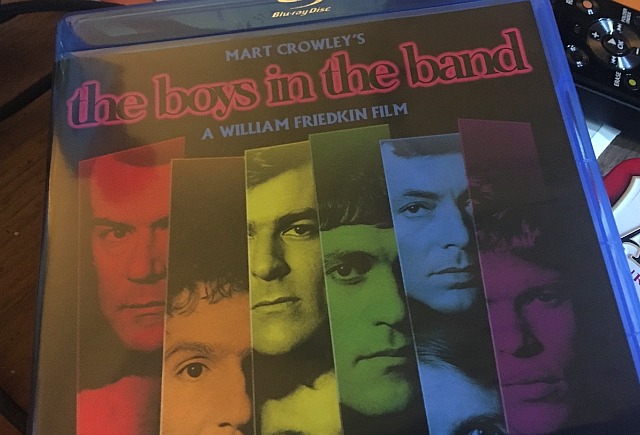

The 50th anniversary Broadway presentation of Mart Crowley‘s The Boys in the Band opened a couple of days ago. The reviews have been pretty good, Ben Brantley notwithstanding. Not being in New York and probably reluctant to shell out $300-plus for a pair of tickets if I were, I’ve done the next best thing — i.e., ordered the Kino Classics Bluray of William Friedkin’s 1970 big-screen adaptation.

From 11.1.17 HE piece, “Reviving A Dated Relic“: “The only question is ‘why?’ Why revive a play that the gay community began to turn its back on around the debut of William Friedkin‘s film version, which opened in March 1970. That was nine months after the June 1969 Stonewall rebellion, and the sea-change in gay consciousness and values that happened in its wake — pride, solidarity, political militancy — had no room for a rather acidic drama about a group of Manhattan gays, gathered at a friend’s birthday party in the West Village, who were consumed by loneliness, misery and self-loathing.

“Mart Crowley‘s revolutionary stage play, which opened off Broadway in April 1968, was a culmination of decades of frustration with straight society’s suppression and/or intolerance of gays mixed with the up-the-establishment freedoms of the late ’60s, but the William Friedkin-directed film version, which opened on 3.17.70, didn’t fit the post-Stonewall mold. And of course it hasn’t “aged well.”

“When Friedkin’s film was re-released in San Francisco in January 1999, Chronicle critic Edward Guthmannwrote that ‘by the time Boys was released in 1970…it had already earned among gays the stain of Uncle Tomism…[it’s] a genuine period piece but one that still has the power to sting. In one sense it’s aged surprisingly little — the language and physical gestures of camp are largely the same — but in the attitudes of its characters, and their self-lacerating vision of themselves, it belongs to another time. And that’s a good thing.’

“Six and a half years ago I allowed that The Boys in the Band ‘deserves respect as a revolutionary play of its time, and, as a film, as a kind of landmark presentation for its candid, amusing, sad and occasionally startling presentations of urban gay men and their lifestyles during those psychedelic downswirl, end-of-the-Johnnson-era, dawn-of-the Nixon-era days, made all the more entertaining and memorable by several bottled-lightning performances (particularly Cliff Gorman‘s as Emory).'”