I’ve been complaining about muddy, murky movie dialogue for years, and enduring constant derision from the HE commentariat (“It’s your fault…hearing aids are cheaper now”). Will the shit talkers apologize now that the actual problem (bizarre sound-mixing habits) has been exposed? Of course not.

Vox copy: “Have you ever been watching a show or movie, and then a character delivers a line so unintelligible you have to scramble to find the remote and rewind? Or activate subtitles?

“Gather enough people together and you can generally separate them into two categories: People who use subtitles, and people who don’t. And according to a not-so-scientific YouTube poll we ran on our Community tab, the latter category is an endangered species — 57% of you said you always use subtitles, while just 12% of you said you generally don’t.

“Why do so many feel that they need subtitles? We got straight to the bottom of it in this explainer, with the help of dialogue editor Austin Olivia Kendrick.”

“Shitty Bull Sound,” posted on 8.5.07:

Every now and then someone writes a looking-back-on-Raging Bull piece (like this one from the Guardian‘s Ryan Gilbey, a nod to the film’s re-release in England on 8.17). And they all report that Martin Scorsese‘s classic wasn’t tremendously popular critically or commercially when it first opened in November of 1980. But what’ s never mentioned is that moviegoers couldn’t hear many of the quieter dialogue scenes with any real clarity, even in the better big-city theatres. And that this almost surely had an effect upon the general reception.

I distinctly remember watching a public screening of Raging Bull in the Sutton Theatre on 57th Street just before Thanksgiving, and leaning forward and cupping my ears and getting angry as I asked myself, “Dammit, why don’t they turn the damn sound up?” I had this reaction every time Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci or Cathy Moriarty were murmuring or muttering their thoughts in their middle-class Bronx apartments, or when “Tommy” the mafia guy was laying things out in his two quiet scenes.

Raging Bull‘s sound was apparently rendered with an intentionally murky-crude quality so it would seem unaffected and working-classy — the idea being that naturalism was equivalent to a kind of aural muck. This almost certainly resulted in tens of thousands of ear-cuppings across the nation given that the sound systems in all but a few big-city theatres back then were atrocious, for the most part. By today’s standards, it was truly the aural Dark Ages.

This sound issue is briefly addressed in the commentary track on the special edition DVD came out in ’05.

I would guess that the murky sound issues probably turned a few people off when it came to recommending Raging Bull to their friends, and that it probably affected the opinions of some critics, if only on a subliminal level. If you can clearly hear what’s being said in a film or a play, you’ll mainly respond to what’s being said — to the content. But if it’s a chore to hear this, then a percentage of critics are going to inwardly say to themselves “fuck this.” And I don’t blame them. So the responsi- bility for Raging Bull‘s underwhelming reception 27 years ago must fall squarely on the shoulders of director Scorsese and editor Thelma Schoonmaker.

I never really heard Raging Bull properly until it came out on laser disc in the early ’90s, and it didn’t sound really great until the special edition DVD hit stores two years ago.

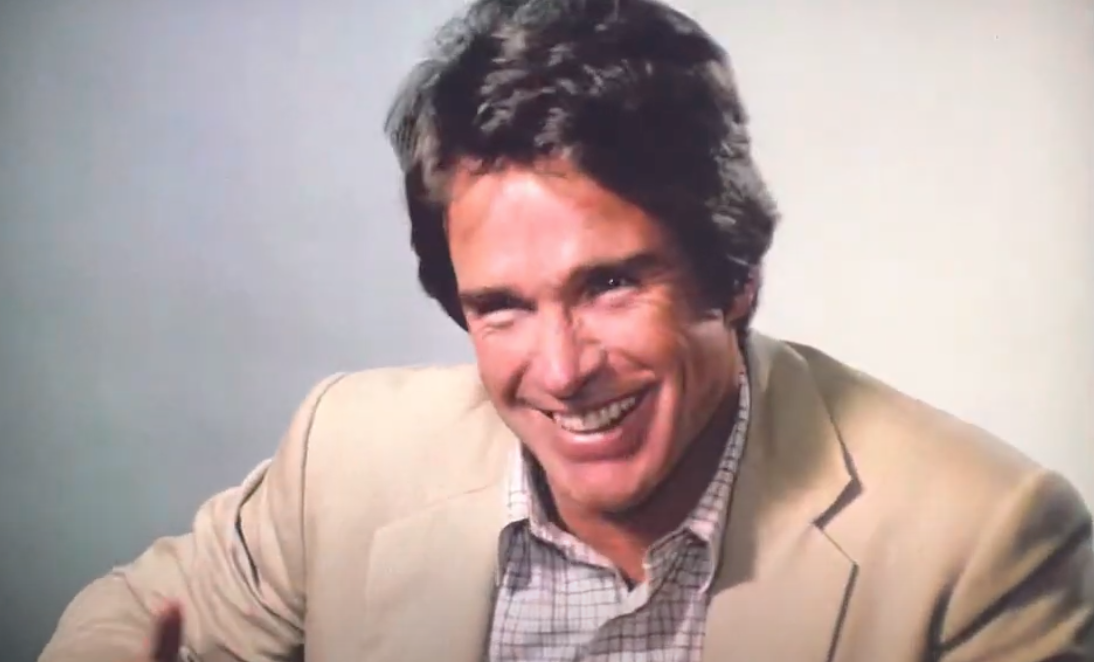

“Beatty’s Sound-Mix Story,” posted on 4.16.22

I’ve been looking for this hilarious story on YouTube for ages. It’s from George Stevens A Filmmakers’ Journey (’85), and nobody’s ever posted it. It’s funny because it reminds us that no matter how divine the inspiration and how arduous and exacting the effort to make the movie turn out right, the last guy on the delivery food chain can still screw it up. From Shane to Bonnie and Clyde to a projectionist’s booth inside London’s Warner cinema.

I noted yesterday that George Stevens, Jr.s documentary ignores The Talk of the Town, one of my favorite second-tier Cary Grant films. It also ignores his father’s 1970 film The Only Game in Town, in which Beatty costarred with Elizabeth Taylor.