I tried to think of something interesting to say about TomKat planning to finally get married in Italy on Saturday, 11.18, but all I could come up with was the idea of being inside their heads for five or six hours via one of those Being John Malkovich mud-tunnel transporting devices, or even being in both their heads simultaneously (weird thought), but it got too strange.

The intrigue is much higher regarding Cruise’s interest in making an indie “political drama” called Lions for Lambs, which reportedly deals with a platoon of U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan, presumably post-9/11. The script is by Matthew Carnahan (State of Play), and Variety’s Michael Fleming says Robert Redford is said to be “likely” to direct as well as play a role. If anyone has a copy….

I am in friendly but fervent opposition to anyone on ANY campus who picks up a microphone and says they feel “actively victimized” by ANYthing except by real, actual, legitimate threats (i.e., possibly being raped, harmed in some physical way or killed).

Sensible, real-world, non-woke opinions are not threats. They simply represent an aspect of the normal rough and tumble of political dispute, which is par for the course if you (ahem) live off-campus.

The phrase “actively victimized” is a woke cliche used by people who fetishize the threat of victimization in order to display their woke bonafides.

Life IS hard and sometimes even scary. It’s not a walk in the park, certainly in the case of woke wimps and candy-asses. It IS a good idea to toughen your hide and maybe wear a helmet. I despise campus wussies and their litany of complaints about everything that doesn’t look, sound or feel “right” or “safe” to them.

Imagine the settlers in a John Ford western going up to Scar, the hostile Comanche chief in The Searchers, and saying “your war paint is not cool…you guys are making us feel actively victimized, and we really don’t feel safe…waaah.”

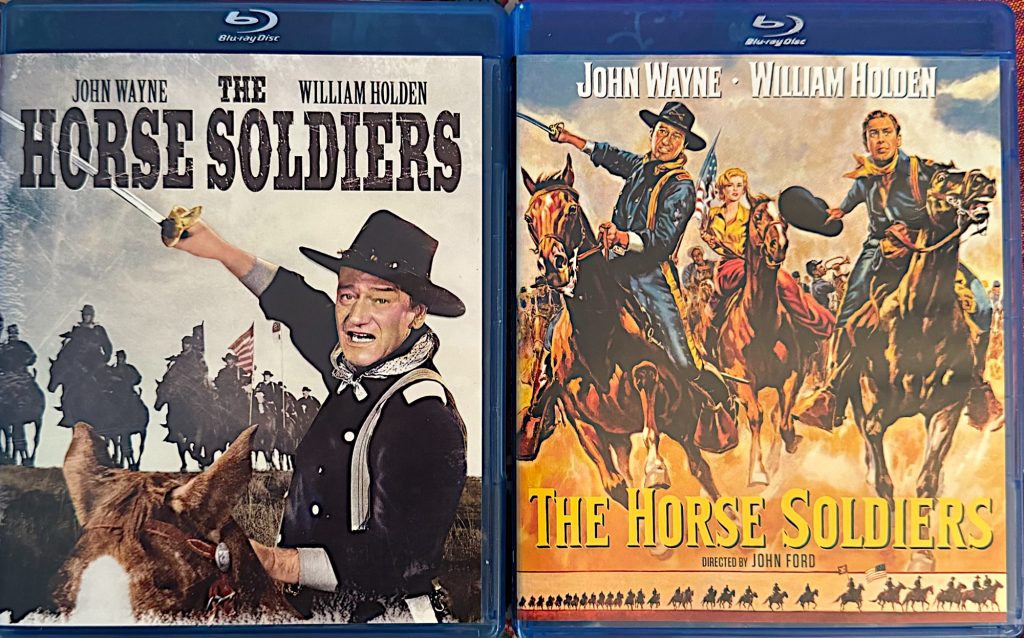

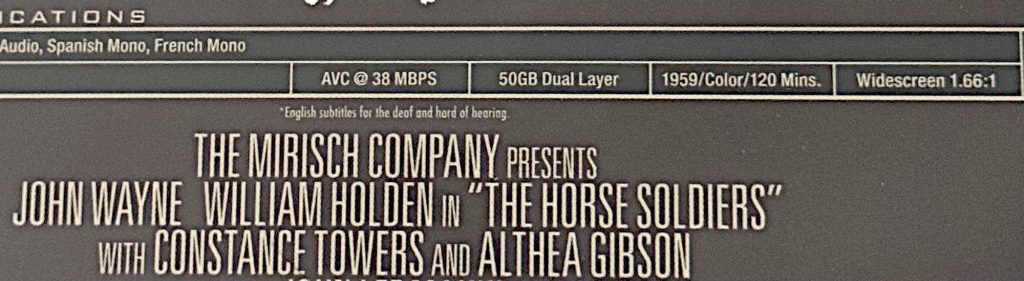

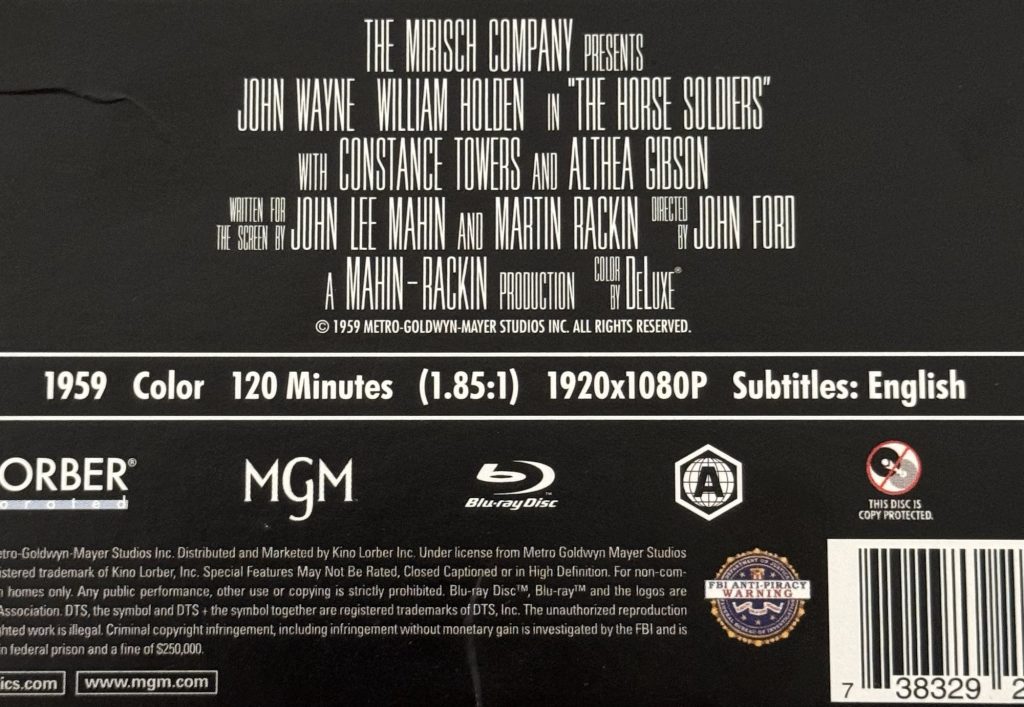

MGM’s 2011 Bluray of John Ford’s The Horse Soldiers (‘59) has a perfectly satisfactory 1.66 aspect ratio, but leave it to Kino Lorber to fuck things up by slicing off the tops and bottoms of the image for its 4K Bluray version, which came out a couple of years ago and which I just bought. Bastards. Presenting this profoundly handsome film within a 1.85 aspect ratio is an act of pure malice. Zero respect, nothing but condemnation.

I’m sorry but while sitting in my third-row seat at the Museum of Moving Image last Saturday evening, I would have been a much happier camper watching John Ford‘s The Horse Soldiers instead of The Searchers.

The former, released in 1959, has never been accused of being a great film — two years ago I called it steady, sturdy mid-range Ford — but it’s very watchable and oddly comforting, and it has no racism or bizarre atmospheric concepts (a family living alone in a water-less, soil-free Monument Valley) or anything that prompts strong disbelief.

That scene in which John Wayne‘s Union troops are hiding in a forest alongside a sizable-sized river as they listen to some Confederate troops sing a marching song, and doing so with the vocal expertise of the Mitch Miller singers and in harmony yet…gets me very time.

HE commenter “brenkiklco”: “Brilliant in patches but quite slight. The action is perfunctory. The charge at Newton Station is rather lamely staged. And there’s scarcely any climax at all. Ford reportedly just wanted to wrap the thing up after a stuntman died on the set. The romance is unconvincing. Most of the performances have that Fordian quality of slight, theatrical exaggeration. A hint of Victorian barnstorming that you either go with or you don’t. But Wayne and Holden make good frenemies, and there are several enjoyable scenes.

Posted on 6.4.22: I’ve had it up to here with the standard narrative about The Horse Soldiers being one of John Ford‘s lesser efforts. I know this sounds like heresy, but it may be my favorite post-1945 Ford film. I know that She Wore A Yellow Ribbon and The Searchers and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance are widely regarded as more substantial and therefore “better”, but I don’t like watching them as much as The Horse Soldiers, and anyone who doesn’t like that can shove it.

A Civil War drama based on Grierson’s Raid of 1863, The Horse Soldiers is steady, solid, midrange Ford — well-produced and well-acted with good character arcs and flavorful Southern atmosphere. Plus it gets extra bonus points for being set in the South (green trees, green grass, plantations, swamps, bridges, rivers) and not in godforsaken Monument Valley.

Handsomely shot by William H. Clothier in a 1.66 aspect ratio, its very easy to watch — every time I pop it in I feel comfortable and relaxed. Partly because it has a minimum of Ford-bullshit distractions. My only real problem is a scene in which rebel troops are heard signing a marching tune exactly like the Mitch Miller singers. I also don’t like a scene in which a furious John Wayne throws down eight or nine shots of whiskey in a row — enough to make an elephant pass out.

There’s a scene in which a boys’ military academy is asked to attack Wayne’s Union regiment — a scene in which a mother drags her 10-year-old son, Johnny, out of a line of marching troops, only to lose him when Johny climbs out of his second-floor bedroom window to rejoin his fellows. It reminds me of that moment when Claudette Colbert collapses in a grassy field as she watches Henry Fonda marching off to fight the French in Drums Along The Mohawk.

I also love that moment in Newton Station in which Wayne senses something wrong when costar William Holden, playing an antagonistic doctor-surgeon, tells him that perhaps a too easily captured Confederate colonel (Carleton Young), an old buddy, isn’t the submissive, easily captured type — “He’s West Point, tough as nails…the man I knew could lose both arms and still try to kick you to death.”

Kino Lorber’s new 4K version of this 1959 film (which lost money, by the way, partly due to exorbitant salaries and producer participation deals) streets on 6.14.22

\

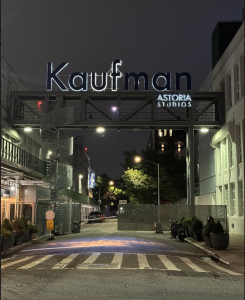

Last night I hopped on the R train (Times Square to Steinway) in order to visit the nominally pleasant but architecturally dreary neighborhood of Astoria, Queens. Talk about your ethnic downmarket vibe. I took a couple of snaps (SAMO graffiti, a guy openly taking a leak) as I wondered how and why anyone would want to live in this kind of vaguely shitty neighborhood.

The precise destination was the Museum of the Moving Image, where the highly touted 70mm restoration of John Ford’s wildly over-praised The Searchers unspooled at 7:30 pm.

The MOMI host told us we were in for a real treat — a 70mm replication of a genuine, bonafide VistaVision version of a luscious color film (shot by Winston C. Hoch) that very few popcorn-munching Average Joes saw in ‘56.

What I saw last night looked like a nice but unexceptional 35mm print that could have played in my home town of Westfield, New Jersey.

“Bullshit!”, I muttered to myself as I sat in my third-row seat. “I’ve been took, tricked, scammed, duped, deceived, flim-flammed, led down the garden path, fooled, boondoggled, lied to, taken to the cleaners, sold a bill of goods”, etc.

Immediately my eyes were telling me that the 70mm restoration is some kind of reverent con job, and that ticket-buying schmoes like myself were being gaslit. “This?” I was angrily saying to myself. “Where’s the enhancement? Where’s the extra-exacting detail that a ‘straight from the original VisaVision negative’ 70mm print would presumably yield?”

The MOMI theatre is seemingly a technically first-rate operation with a nice big screen, but what a fuming experience I had. No “bump” at all over the versions I’ve watched on various formats over the years. No bump whatsoever, fuckers! Plus some shots looked overly shadowed, and some looked a tad bleachy.

Technically sophisticated friendo who knows his stuff: “In order to present a film print properly — especially 70mm — more things must come together than you might imagine in your worst nightmare.”

Thanks, powers-that-be! Thanks for lying right through your teeth!

Have you ever been to Monument Valley? It’s kinda like the moon. Beautiful but barren. No water, no nutritious soil, no grass for cattle to eat, nothing at all to sustain life. It’s a completely ridiculous notion that anyone would have settled there.

Where did Ethan’s canteen water come from? How did anyone clean themselves or wash their clothes, much less take a bath? How did the families “attend to business” in any sort of half-sanitary fashion without an outhouse, much less toilet paper? No one had any perfumes or colognes or deodorants. They all stunk to high heaven.

The racism in this film is beyond odious. It’s appalling how Ford depicted Native Americans as bloodthirsty simpletons…savage, murderous, sub-human. Those shots of captured white women whom Ethan dismisses with disgust (‘They ain’t white!’), howling and shrieking like young witches whose brains had been removed….a ghastly moment.

Plus Scar (played by Henry Brandon, the blue-eyed gay actor who turned up 20 years later in Assault on Precinct 13) surely began to sexually enjoy Natalie Wood’s “Debbie” in her early teens, and she didn’t have children?

Why did Ford never shoot during magic hour? The natural glaring sunlight seems to overwhelm the wonderful brownish-red clay colors in the powdery soil. The only interesting dusky compositions were shot inside a sound stage.

On top of which the toupee-wearing John Wayne had begun his descent into overweight-ness. He was a much slimmer fellow when he made “Hondo.”

I finally couldn’t stand it. I left around the 85-minute mark and forlornly strolled across a mostly vacant 36th Street to Tacuba Cantina Mexicana and ordered some unexceptional grub.

With the suggestions and admonishings of the HE commentariat, I’ve added seven films to my 1966 roster for a total of 22.

My hands-down choice for 1966’s three finest are Michelangelo Antonioni‘s Blow-Up, Robert Bresson‘s Au Hasard Balthazar and Richard Brooks‘ The Professionals.

My second group of 12 include Robert Wise‘s The Sand Pebbles, Bernard Girard‘s Dead Heat on a Merry Go-Round, Fred Zinnemann‘s A Man For All Seasons, John Frankenheimer‘s Grand Prix and Seconds, Jack Smight‘e Harper, Mike Nichols‘ Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Arthur Penn‘s The Chase, Irvin Kershner‘e A Fine Madness, Charles Walters‘ Walk, Don’t Run, Claude Lelouch‘s A Man and a Woman and Billy Wilder‘s The Fortune Cookie.

The third group of seven include Gillo Pontecorvo‘s The Battle of Algiers, Sergio Leone‘s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (I didn’t post it yesterday because I’ve never liked Leone, but I have to at least recognize this film’s iconic status), Ingmar Bergman‘s Persona (I’m ashamed for having forgotten it), Jiri Menzel‘s Closely Watched Trains (intriguing Czech new-waver), Michael Anderson and Harold Pinter‘s The Quiller Memorandum, John Ford‘s 7 Women (saw it once back in the ’80s — a respectable ensemble film), Jean-Pierre Melville‘s Le deuxième souffle

I’ve never seen Milos Jancso‘s The Roundup. Howard Hawks‘ El Dorado didn’t open stateside until 6.7.67 so it doesn’t count. Jean-Luc Godard‘s Made in USA doesn’t count because it was blocked for over four decades over a rights issue and wasn’t released until 2009.

[Partly borrowed from “Peak Years“, posted on 3.11.13]:

Which present-tense, brand-name directors are peaking right now? In 2024, I mean. Generally speaking peak director runs last around ten years, sometimes a bit longer. You would think 15 or 20 or even 25 years would be closer to the norm, but I’m not talking about mere productivity or financial success — I’m talking about peak years, great years.

Two things have to happen for a director to enjoy a special inspirational run. One, he/she has to be firing on all cylinders — adventurous attitude, good health, relentless energy. And two, the culture has to embrace and celebrate his/her output during this run of inspiration.

Just being a gifted filmmaker doesn’t cut it in itself — the public (or at the very least the critics and the award-bestowing fraternity) also has to agree.

David Lean had a high-quality ten-year run run from Brief Encounter (’45) through Summertime (’55), but his prime-zeitgeist period lasted only eight years — The Bridge on the River Kwai (’57) to Dr. Zhivago (’65). The poorly received Ryan’s Daughter nearly finished him off, but then he came back in ’84 with A Passage to India.

John Ford‘s zeitgeist decade ran from The Informer (’35) to My Darling Clementine (’46), then he began to caricature himself with his Monument Valley western films of the late ’40s and ’50s. Ford then resurged with The Horse Soldiers (’59) and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (’62).

Alfred Hitchcock did superb work in the ’30s and ’40s, but his window of mythic greatness lasted only nine years — Strangers on a Train (’51) to Psycho (’60).

Billy Wilder‘s grace period ran ten years — Sunset Boulevard (’50) to The Apartment (’60).

Francis Coppola‘s window ran from The Godfather (’72) to One From The Heart (’82).

Oliver Stone had a 13-year window — Salvador (’86) to Any Given Sunday (’99).

So far [written in ’13] Alejandro Gonzales Inarritu has had a decade-long grace period — Amores perros (’00) to Biutiful (’10).

David Fincher has enjoyed an eleven-year window so far — Fight Club (’99) to The Social Network (’10).

In HE’s book Geta Gerwig is cuurently peaking, obviously, although the prospect of her making a Narnia film depresses me. Todd Phillips, who pole-vaulted up to a new level with 2019’s Joker and appears to have a slam=bang sequel with Joker: Folie a Deux, is peaking bigtime as we speak. Who else?

In an 11.1.11 interview with N.Y. Times columnist Frank Bruni, Alexander Payne, who’d recenty turned 50, admitted that he’d made too few movies up to that point, and that he intended to pick up the pace.

“I’m in my prime right now,” Payne said. “I still have energy and some degree of youth, which is what a filmmaker needs.”

Is Payne concerned about using it before losing it? “Oh yeah,” he said. “Big time. You look at how many years you have left, and you start to think: How many more films do I have in me?”

He mentioned, for the second time in our talks, that Luis Buñuel didn’t really get going until he was in his late 40s. That consoles him. The Descendants, then, isn’t just a movie. It’s a marker, a dividing line between his slowly assembled oeuvre until now, including Election (1999) and About Schmidt (2002), and the intended sprint ahead.

“I want to move quickly,” he said, “between 50 and 75.”

On the other hand Andrew Sarris‘s remark about artists having only so much psychic essence (i.e., when the cup has been emptied, there’s no re-filling it) also applies.

Sidenote: While I did pretty well as a journalist and a columnist in the ’90s and early aughts, my big decade began in ’06 when I took HE in to a several-posts-per-day bloggy-blog format. Everything was pretty great for 13 years until the wokester zealots ganged up on me in ’19 and ’20.

Longer version: Fuck your sentimental boomer attachments to riveting hot-button movies that ruled the roost between the late ‘60s and Iron Man (‘09). GenX is mostly running the show now but down the road we’ll be taking the fuck over, and if you think there’s too much third-rate, zone-out streaming content now, wait until we get our hands on the gears.

You want some attempts at old-fart, boomer-type flicks? There aren’t any. Try original content longform streaming, and if that’s not nourishing enough, tough.

All we care about are jizz-whizz fiicks — IP reboots, moronic romcoms and comedies, VFX and horror. And we definitely don’t want to adapt books or plays — eff that noize.

We are going to run this business into the ground, man.

A quarter-century hence the corpses of Ben Hecht, John Ford, Spencer Tracy, Daryl F. Zanuck, Gregg Toland, Jean Arthur, John Huston, Ida Lupino, Nicholas Ray, Agnes Varda, Tom Cruise, Howard Hawks, Billy Wilder, James Stewart, Stanley Kubrick, Alfred Hitchcock, Meryl Streep, Oliver Stone and Kevin Costner will be spinning in their graves on a permanent basis.

20 years from now people are going to be saying “wow, remember The Fall Guy? What a great film!”

Login with Patreon to view this post

In HE’s judgment, 25 exceptional, high-quality films were released in 1959. (There were another 9 or 10 that were good, decent, not bad.) By today’s standards, here’s how the top 25 rank:

1. Billy Wlder‘s Some Like It Hot (released on 3.29.59)

2. Alfred Hitchcock‘s North by Northwest (released on 7.1.59)

3. John Ford‘s The Horse Soldiers (released on 6.12.59)

4. George Stevens‘ The Diary of Anne Frank (released 3.18.59)

5. Stanley Kramer‘s On The Beach (released on 12.17.59)

6. William Wyler‘s Ben-Hur (released on 11.18.59)

7. Alain Resnais‘s Hiroshima, Mon Amour (released in France on 6.10.59)

8. Lewis Milestone‘s Pork Chop Hill (released on 5.29.59)

9. Otto Preminger‘s Anatomy of a Murder (released on 7.2.59)

10. Francois Truffaut‘s The 400 Blows (released in France on 5.4.59)

11. Howard Hawks‘ Rio Bravo (released on 4.4.59)

12. Sidney Lumet‘s The Fugitive Kind (released on 4.14.59)

13. Tony Richardson‘s Look Back in Anger (released on 9.15.59)

14. Grigory Chukhray‘s Ballad of a Soldier (released on 12.1.59)

15. Robert Bresson‘s Pickpocket (released on 12.16.59)

16. Robert Wise‘s Odds Against Tomorrow (released on 10.15.59)

17. Delbert Mann‘s Middle of the Night (released on 6.17.59)

18. Robert Stevenson‘s Darby O’Gill and the Little People (released on 6.26.59)

19. Fred Zinnemann‘s The Nun’s Story (released on 6.18.59)

20. Guy Hamilton‘s The Devil’s Disciple (released on 8.20.59)

21. Roger Vadim‘s Les Liaisons Dangereuses (released on 9.9.59)

22. Richard Fleischer‘s Compulsion (released on 4.1.59)

23. Val Guest‘s Expresso Bongo (released on 12.11.59)

24. Carol Reed‘s Our Man in Havana (released in England on 12.30.59 / stateside on 1.27.60)

25. J. Lee Thompson‘s Tiger Bay (released in March 1959)

Bonus:

Charles Barton‘s The Shaggy Dog (released on 3.19.59).

Why in the world would Martin Scorsese want to make another Jesus film? 35 years ago he delivered his magnum opus with The Last Temptation of Christ…he did it, nailed it, nothing left to prove. Especially with Terrence Malick‘s The Way of the Wind, a parable-driven Jesus flick he’s been editing for somewhere between four and five years, possibly debuting later this year. On top of which belief in Christian dogma has been plummeting for decades, and especially this century.

At a Berlinale press conference earlier today Scorsese said he’s still “contemplating” the approach to his Jesus film.

“What kind of film I’m not quite sure, but I want to make something unique and different that could be thought-provoking and I hope also entertaining. I’m not quite sure yet how to go about it. But once we finish our rounds here of promoting [Killers of the Flower Moon], maybe I’ll get some sleep and then wake up and I’ll have this fresh idea on how to do it.”

HE suggestion: Forget the Nazarene and do another gangster flick, only faster-moving this time. Faster and less contemplative and no old guys. As John Ford was to the western, Martin Scorsese is to northeastern-region goombah crime flicks.

Yesterday Indiewire‘s Anne Thompson posted an interview with Killers of the Flower Moon screenwriter Eric Roth, and in so doing passed along, for what seemed like the umpteenth time, the story of how Roth and Martin Scorsese‘s 209-minute period melodrama began as one thing (a traditional investigative crime drama) and then became something else (a sprawling white-guilt wokester saga about the the ache of the Osage murder victims in the early 1920s, and particularly the evil of the white Oklahoma yokels).

Leonardo DiCaprio had initially been set to play the intrepid Bureau of Investigation agent Tom White, the guy who ultimately indicted three of the killers but was unable to bring many other killers to justice. (Leo excitedly told me this during a 2019 party at San Vicente Bungalows.) But sometime in early 2020 and perhaps during the beginning of Covid, Leo had a change of heart.

He didn’t want to play White because — let’s be honest — the woke movement had taken hold in progressive Hollywood circles and he didn’t want to be attacked or sneered at for playing a heroic white savior — a politically uncool thing in the Hollywood climate that was then unfolding.

Leo instead wanted to play the none-too-bright Ernest Burkhart, who became complicit in the murders of certain Oklahoma Osage natives by way of his fiendish uncle (Robert De Niro‘s ‘King” Hale), and who also came close to murdering his own Osage native wife, Mollie Burkhart (Lily Gladstone).

“At the beginning, Scorsese and Roth embraced a real John Ford Western,” Thompson writes.

Roth: “The early versions of the KOTFM screenplay were as much about Tom White as they were about the crime and everything else, and in that sense they were closer to the book. So it wasn’t a mystery in that sense.

“But then Marty began to express a bigger thing, which he’s so right about. It’s not a ‘who done it’ — it’s ‘who didn’t do it.’ As a social comment.”

God save Joe and Jane Popcorn from “social comment”, or more specifically social instruction.

Marty and Leo’s idea, in other words (allow me to offer an interpretation), was that we’re all guilty…all of us…back then and today.

In the same way that Randy Newman, in his 1970 song “Rednecks“, expanded the concept of racist attitudes and behaviors from the rural south to the entire country (“We don’t know our ass from a hole in the ground”), Killers of the Flower Moon would essentially serve as an indictment of white racism all over, in every nook and cranny of the country…we’re all dirty and guilty and reprehensible as fuck.

There’s no way the wokesters would come after Marty, Eric and Leo if they made a movie like this, the thinking presumably went, but if they made a “hooray for Tom White” flick, they might be indicted or semi-cancelled for being old-fashioned or blind to the new woke enlightenment or whatever.

Sometime in early ’20 or thereabouts, Roth got a call from Scorsese. “Are you sitting down?” Marty said. “Because Leo has a big idea.”

Roth: “Leo didn’t want to be the great white savior. Very smart. And the more complicated part was the husband [Ernest Burkhart] and complicated for many reasons, but probably the most interesting is somebody who’s in love with somebody and trying to kill them.

“We always embraced [Mollie] as the centerpiece of the movie.” [HE to Roth: Why? She doesn’t say anything or do anything — she’s completely passive.] “We had many, many things that dealt with the Osage, the Osage customs, the Osage world.”

What?

In fact Leo’s decision to submit to woke sensibilities (and Marty and Eric’s decision to go along with this) ensured that Killers of the Flower Moon would become a long, half-mystifying, eye-rolling, ass-punishing slog — a guilt trip movie without any story tension to speak of.

And here we are now, unlikely to bestow any top-tier awards** upon KOTFM except, most likely and very depressingly, the Best Actress Oscar to Gladstone for basically playing a passive victim of few words, a sad-eyed lady of the oil-rich lowlands who sits around in native blankets and gives dirty looks to all the evil crackers as Leo injects her with poisoned insulin…fascinating!

** Except for the musical score by the late Robbie Robertson — this is likely to win.

Really Nice Ride

Really Nice RideTo my great surprise and delight, Christy Hall‘s Daddio, which I was remiss in not seeing during last year’s Telluride...

More » Live-Blogging “Bad Boys: Ride or Die”

Live-Blogging “Bad Boys: Ride or Die”7:45 pm: Okay, the initial light-hearted section (repartee, wedding, hospital, afterlife Joey Pants, healthy diet) was enjoyable, but Jesus, when...

More » One of the Better Apes Franchise Flicks

One of the Better Apes Franchise FlicksIt took me a full month to see Wes Ball and Josh Friedman‘s Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes...

More »

- The Pull of Exceptional History

The Kamala surge is, I believe, mainly about two things — (a) people feeling lit up or joyful about being...

More »  If I Was Costner, I’d Probably Throw In The Towel

If I Was Costner, I’d Probably Throw In The TowelUnless Part Two of Kevin Costner‘s Horizon (Warner Bros., 8.16) somehow improves upon the sluggish initial installment and delivers something...

More » Delicious, Demonic Otto Gross

Delicious, Demonic Otto GrossFor me, A Dangerous Method (2011) is David Cronenberg‘s tastiest and wickedest film — intense, sexually upfront and occasionally arousing...

More »