HE is sorry to report that director Roger Michell has passed at age 65 of an unstated cause. It can be deduced that his death was sudden and unexpected, as Michell was at Telluride only three or four weeks ago with his latest film, The Duke; he was also talking about working on a forthcoming documentary.

Login with Patreon to view this post

Herewith are four reviews of four Terrence Malick films that opened between 2012 and 2019 -- To The Wonder, Knight of Cups, Song to Song and A Hidden Life. Plus a July 2012 essay about how Malick's enablers have done him no favors. It's quite a saga.

Login with Patreon to view this post

Another tip of the hat to Robert Redford, who's been on the planet for 85 years as of today. Never forget that his legend is rooted in a 12-year peak period -- a heyday that began with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid ('69) and came to an end with Brubaker ('80).

Login with Patreon to view this post

Remember what supermodels used to look like ten, twenty, thirty years ago? We all understood the genetic, glowing signals. Rail-thin, sleek, elegant, striking, beautiful, wow. Well, according to the September issue of Vogue, times have changed. Today’s supermodels exemplify the beauty of great genes but also (and more importantly) diversity, varying sizes, wokeness, women supporting women, equality, no one being marginalized, etc.

And just to drive the point home, the eight Vogue models heralded in the new issue — Kaia Gerber (spawn of Cindy Crawford), Anok Yai, Precious Lee, Bella Hadid, Sherry Shi, Ariel Nicholson, Yumi Nu and Lola Leon (daughter of Madonna and Carlos Leon) — all have their hair in a tight bun or pulled into a ponytail. We get it..

The fashion industry has never been about what straight guys think, of course, but what this photo basically confirms is that the age-old pleasure of guys gazing at supermodels is…well, perhaps not “over” but more of a mixed-bag activity. Because two or three of these women, no offense, are not classic head-turners.

The devastatingly beautiful Yai fits the classic mold, of course; ditto Gerber, Hadid, Leon and Li. The alabaster-skinned, ginger-haired Nicholson…okay, fine. The plus-sizers represent a different aesthetic.

Friendo: “This is just virtue-signaling crap. Instagram and Tik Tok still show what kinds of women draw eyeballs. Honestly, has the world ever beheld a more censorious, strident, militant, punishing generation? It’s like in Orwell where things mean the opposite — Ministry of Love, Ministry of Truth, etc. The idea that they love everyone and marginalize no one and everyone is as accepted as they are is, at the very least, PARTIAL BULLSHIT. You agree with them or you’re destroyed. Accept the new aesthetic or face banishment.”

From left: Kaia Gerber (daughter of Cindy Crawford) wears Tom Ford. Anok Yai wears Ralph Lauren Collection. Precious Lee wears Carolina Herrera. Bella Hadid wears Christopher John Rogers. Sherry Shi wears Proenza Schouler. Ariel Nicholson wears Christopher John Rogers. Yumi Nu wears Mara Hoffman. Lola Leon (daughter of Madonna and Carlos Leon) wears Michael Kors Collection. Hair, Lucas Wilson; makeup, Jen Myles. Fashion Editors: Tonne Goodman and Gabriella Karefa-Johnson.Photographed by Ethan James Green, Vogue, September 2021.

One thing you’ll never, ever see in an action film is a supporting player (bad or neutral guy) who stands up and is ready to fight or shoot it out with a lead guy, and then — very sensibly! — changes his mind when he realizes that beating or out-drawing the lead guy isn’t in the cards. It happened 52 years ago in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, but it hasn’t happened since.

If I’m wrong please remind me of another scene that works like this (i.e., “Uhhm, wait, hold on…I can’t win this one.”).

The card player’s name was Donnelly Rhodes, and he died three and a half years ago. He was 40 or so when he shot this scene with Robert Redford, Paul Newman and director George Roy Hill.

Working backwards from today, here are (a) Hollywood Elsewhere's ten best fictional presidents and (b) best portrayals of historical presidents in feature films. Yes, I'm allowing for Saturday Night Live and other comedic portrayals.

Login with Patreon to view this post

Does anyone remember Dave Karnes? Or more precisely Michael Shannon‘s portrayal of Karnes in Oliver Stone‘s World Trade Center (’06)?

Karnes was the ex-Marine who ducked out of his office job in Wilton, Connecticut, and drove into Manhattan on the afternoon of 9/11/01 and made it through police barriers and onto the WTC site by dinner hour, and who later found Port Authority cops John McLoughlin (Nicolas Cage) and Will Jimeno (Michael Pena) buried under the mashed-up rubble, and brought the rescue teams to their aid.

World Trade Center was an odd Stone film because it had nothing to “say” except (1) “McLoughlin and Jimeo sure went through hell that day”, but (2) “thank God for Karnes and his dogged persistence.” No politics, no Hollywood leftie attitude — just a straight drama about a lot of good people pulling together to save a couple of guys from the jaws of death. A movie about caring, family, duty, perseverance.

If Karnes hadn’t put on his Marine uniform and gotten himself a Marine haircut at a Stamford barbershop and driven down to Manhattan and all, it’s quite possible McLoughlin and Jimeno might not have survived. (Who knows?) Shannon portrays him as a bit of a nut, but a good kind of nut in a situation like 9/11 — a guy who laser-beams right into what needs to be done, and then does it.

Curiously, Stone decided to omit a character detail that I’ve always found really interesting. Karnes drove into Manhattan in a recently purchased Porsche 911 convertible, and at times, according to a 9.02 Slate story by Rebeca Liss, at speeds of 120 mph.

That’s a fascinating trait for a 9/11 savior — tear-assing down the Connecticut Turnpike and the Henry Hudson Parkway in a muscle car with the top down, and stopping at a McDonald’s along the way.

Why didn’t Stone show this? My theory is that he wanted Karnes to appear selfless and monk-like — a slightly loony military saint. And I think he knew this impression wouldn’t fly with audiences if he had Karnes driving a Porsche 911 because a lot of people think that guys who drive Porsches are dickheads.

But I had read about Karnes and his Porsche two or three years ago and was waiting for that shot. I felt that Stone sold Karnes short by trying to simplify him into a ex-Marine who resembled the real-deal Karnes in some ways but not entirely.

Ned Beatty‘s recent passing took a lot of us back to John Boorman‘s Deliverance (’72). Released 49 years ago, it was perfect for its time, but would probably not be right for ours. Sometimes it’s better to leave well enough alone.

It’s too white, for one thing. And I’m not sure audiences would want to see an action thriller triggered by the anal rape of an overweight suburban salesman by some unwashed toothless hillbilly — that’s some rough stuff. But what a primal, fascinating tale.

Deliverance was the first and possibly the last well-made drama that scared viewers half to death with the idea that city and suburban folk should stay the hell out of the primitive areas of this country and far away from the residents of these cultures. A film that said “you don’t want to know those people, and they don’t want to know you.”

The basic attraction of Deliverance is the thrill, danger and horror of four suburban guys on a nourishing canoe trip down a beautiful wild river, and how, for a while, it all seems like the greatest woodsy adventure ever.

Until everything turns around in the darkest way imaginable…sexual assault, bloody murder, hiding a body, another killing, a subsequent life or death struggle to survive by having to kill again and and then, back in civilization, having to lie their way out of a possible arrest and prosecution in the aftermath. And all it happening in the midst of a bucolic hillbilly hell — leafy, primal, horrific.

Did Deliverance paint an incorrect and malicious portrait of deep-rural types? Yes, and them’s the breaks. But there’s never been another horror film quite like it. And despite the restrained realistic vibe and first-rate dialogue and Vilmos Zsigmond‘s magnificent cinematography, that’s exactly what it is — a southern nightmare trip.

I wonder how familiar under-40 audiences are with Deliverance, and whether a remake could work. Would there be complaints from the LGBTQ community that a depiction of male rape might somehow demonize homosexuality? (I’ve always wondered if the male rape scene in Pulp Fiction was inspired by Deliverance.)

I’m also wondering how the original would have played if Sam Peckinpah had directed it. It’s probably for the best that he didn’t. The film benefits from Boorman’s deft, somewhat artsy touch.

I’m also wondering how it would’ve played if Gene Hackman, Lee Marvin or Jack Nicholson had played the Jon Voight part. Or if Marlon Brando had played the Burt Reynolds role. Or if Donald Sutherland or Charlton Heston had taken a whack at it.

Kirk Douglas‘s last brawny action film was Jeff Kanew‘s Eddie Macon’s Run (’82), which he made in his mid 60s. He continued to play strong characters in challenging situations into the early aughts (The Man From Snowy River, Tough Guys, Final Countdown, Greedy), but the rugged action stuff seemed ill advised after Eddie Macon — why push it?

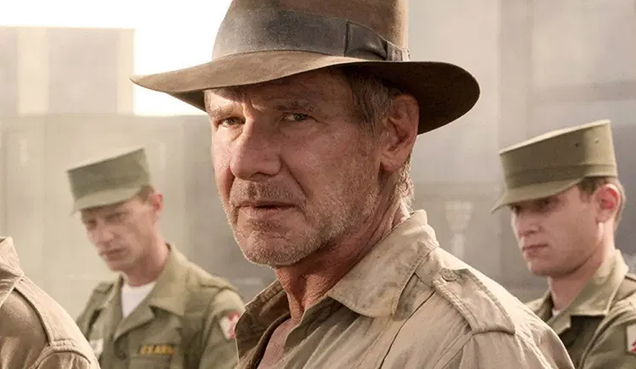

Harrison Ford (born on 7.13.42) was different — Douglas was Douglas but Ford had his own path to follow, and so he continued to make action films into his ’70s. Alas, he fractured his ankle (or was it his leg?) during shooting of Star Wars: The Force Awakens in 2014, when he was 71. (More bad luck than age-related.) And then those piloting mishaps occured — the Venice golf-course crash on 3.5.15 (the plane’s fault, not Ford’s), and two strategic landing errors — one at John Wayne Airport on 2.3.17, and a second at Hawthorne airport on 4.24.20.

And now he’s suffered a shoulder injury on the set of Indiana Jones 5, and is taking a break from filming while the wound is treated.

We all admire Ford’s spirit and gumption, but he’ll be 79 next month — it’s not exactly a surprise that he’s succumbed to injuries and errors of judgment, is it? Same difference when Robert DeNiro, a year younger than Ford, damaged one his quad muscles last month while working on Martin Scorsese‘s Killers of the Flower Moon.

Part of the syndrome is psychological, I’m guessing. When presented with a physical challenge of some kind, older guys will say to themselves “I might be in my 70s but I feel like I’m 47…fuck it, I can do this, no sweat.” And then they do the thing and the body — surprise! — doesn’t perform as expected.

I should have watched something here-and-now last night (Bo Burnham Inside, Hacks, The Sons of Sam) but like a jackass I streamed the 4K version of Raiders of the Lost Ark, which I’d heard looks extra sharp and luscious. Well, it looks good, sure, but calm down. I loved Raiders when it first popped in June of ’81, which led to my seeing it too many times. But now? Again? For the ninth or tenth time?

Ten minutes into last night’s viewing I was muttering four things: (1) “I really can’t watch this any more…I’m sick of it,” (2) “All of the jokes and bits and tricks that seemed so cool 40 years ago have been over-mined and over-imitated, and have lost their pizazz,” (3) “The idea was to make thrill comedy out of the conventions of old Saturday matinee serials, but so much of the action choreography seems silly now…Harrison Ford chased through the jungle by 15 or 20 natives with bows-and-arrows and poison dart blowguns, and he doesn’t get tagged once, even when he’s swimming towards the plane?…slender Karen Allen drinking an overweight Tibetan guy under the table?…the cute little monkey who alerts the Nazis to Allen’s hiding place inside a large woven basket (bad!) is the same critter who pretends to moan and cry when Ford is moping over her apparent death…the film is jam-packed with little irritations like this”, and (4) “Allen’s constant shrieking of ‘Indiiieeee!’ is enough to drive you nuts.”

The only bit that still works (it actually made me laugh out loud, and I’m a total LQTM type) is when Ford casually pulls out a pistol and shoots the scary North African guy with a huge sword. And this film would be almost nothing without John Williams‘ rousing, haunting, at times even spooky score…seriously, none of the big moments would work without the music.

My favorite Raiders film remains Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade…it’s funnier and spritzier that the original.

Quick — name some Spielberg films that have aged really well. Answer: There aren’t that many. Schindler’s List, of course. Minority Report, E.T. Saving Private Ryan except for the awful bookends, Duel, and two portions from Close Encounters — the silent opening-credits followed by the crash-crescendo of the Sonoran desert plus the air-traffic controller sequence. For the most part early Spielberg flicks are sugary soft drinks. Very soothing and satisfying if you’re hot and thirsty, but most of them don’t linger. They’re not really intended to. He has a great cinematic eye and a fine sense of strategic choreography, but he’s not what anyone would call a deep, moody, meditative filmmaker.

I’ve watched these YouTube clips from J.C. Chandor‘s Margin Call at least a dozen times and possibly more than that. They radiate serious grip — a magnificent feeling of real-world psychological tension and unspoken currents — the kind of thing that I live for (or used to live for) when I went to screenings and public showings.

Margin Call premiered at Sundance in January ’11 (I attended the first press screening at the Holiday Cinemas), and by the time it opened the following October Chandor was well branded as a leading young light — a serious-focus, auteur-level helmer who, it was presumed, would make moviegoing for educated over-35s a slightly less draining experience.

This presumption was happily fulfilled with the brilliant All Is Lost (’13), containing Robert Redford‘s greatest performance, and A Most Violent Year (’14), an excellent Queens-based noir about a family business.

In July 2014 Chandor was hired to direct Deepwater Horizon, but by January 2015 he’d left the project over creative differences (i.e., head-butting arguments with Mark Wahlberg). And then, four years later, came Triple Frontier, a Netflix thing which I found fully realistic and satisfying except for the finale when the thieves decide to give a significant portion of the dough to Ben Affleck‘s calorically-challenged daughter. If it was my call, she’d get Affleck’s share and no more.

Last August Chandor, one of the true good guys of cinema and a reach-for-the-sky craftsman and visionary, was hired to direct Kraven, The Hunter with Aaron Taylor-Johnson playing the titular character. The release date — 1.13.23 — tells you everything.

We all have to earn money and keep the lamps burning, but the idea of Chandor directing Kraven is, no offense, shattering.

During the last 20 or 25 minutes of Peter Yates‘ The Hot Rock (’71), professional thief John Dortmunder (Robert Redford) arranges for a deep-voiced hypnotist named Miasmo (Lynne Gordon) to put an unsuspecting safe-deposit-box teller into a kind of waiting trance state.

The trigger term that will make the teller obey any command is “Afghanistan bananistan”, a deliberately silly invention (presumably dreamt up by screenwriter William Goldman)…a noun-switch takeover in the same vein as “Oscar schmoscar”…obviously.

It goes without saying that there’s no reason on earth for Miasmo to have invented a similar-sounding term, “Afghanistan banana stand.” Why would she do that? Even with a silly attitude what do bananas have do with Afghanistan? Has anyone ever heard of a Kabul fruit seller restricting his goods to just bananas? It’s lame — a needlessly literal term when the much simpler “Afghanistan bananistan” will suffice.

And yet the Hot Rock Wikipedia page nonsensically claims that Miasmo says “Afghanistan banana stand”, and now a copy writer for the Criterion Channel has parroted this interpretation. Can we please nip this one in the bud? “Bananistan” is standard form — “banana stand” is ridiculous.

Really Nice Ride

Really Nice RideTo my great surprise and delight, Christy Hall‘s Daddio, which I was remiss in not seeing during last year’s Telluride...

More » Live-Blogging “Bad Boys: Ride or Die”

Live-Blogging “Bad Boys: Ride or Die”7:45 pm: Okay, the initial light-hearted section (repartee, wedding, hospital, afterlife Joey Pants, healthy diet) was enjoyable, but Jesus, when...

More » One of the Better Apes Franchise Flicks

One of the Better Apes Franchise FlicksIt took me a full month to see Wes Ball and Josh Friedman‘s Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes...

More »

If I Was Costner, I’d Probably Throw In The Towel

If I Was Costner, I’d Probably Throw In The TowelUnless Part Two of Kevin Costner‘s Horizon (Warner Bros., 8.16) somehow improves upon the sluggish initial installment and delivers something...

More » Delicious, Demonic Otto Gross

Delicious, Demonic Otto GrossFor me, A Dangerous Method (2011) is David Cronenberg‘s tastiest and wickedest film — intense, sexually upfront and occasionally arousing...

More » Queer for “Virginia Wolff” Color Snaps

Queer for “Virginia Wolff” Color SnapsPosted on 11.27.23: “One thing that’s always bothered me about Virginia Wolff is that George and Martha’s young guests —...

More »