I wangled a last-minute entry into a big hoo-hah for Warren Beatty‘s Reds (’81) at the Directors Guild of America theatre last night. It was a four-part affair — a buffet reception at 6 pm, screening at 7 pm, coffee, fruit and brownies in the lobby during intermission, and then a q & a with Beatty and interviewer Bennett Miller (the esteemed Capote director) sometime around 10:40 pm.

Capote director Bennett Miller and Reds director-producer-star Warren Beatty during Saturday night’s q & a following a screening of Reds at the DGA on Saturday, 9.30.06.

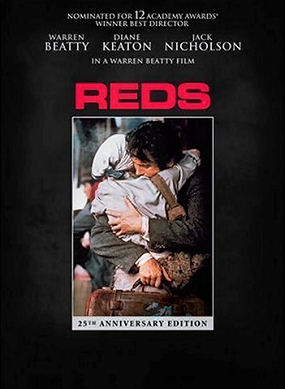

This and Wednesday’s special screening at the New York Film Festival is part of a promotion for the Paramount Home Video double-disc DVD that “streets” on 10.17. The longish, Oscar-winning epic will also open theatrically for a week in New York and Washington, D.C. on 10.6, and in L.A. (at the Arclight) on 10.13.

I hadn’t seen Reds in over 20 years (I haven’t watched the versions on VHS and laser disc due to gross over-scanning), and I was stirred and turned on all over again — it’s a very smart, wonderfully adult historical epic that delivers at a consistently intimate-intellectual level. I was also startled at how incredibly young everyone (Beatty, Diane Keaton, Jack Nicholson, Edward Herrman) looked back then.

At the same time I was wondering if today’s under-30 viewers will care very much about a film as rich and densely political as this one. The dual servings of a troubled-relationship movie (i.e., the ups and downs between Beatty’s free-thinking John Reed and Keaton’s Louise Bryant) and a very nicely layered portrait of old-school lefty idealism may seem a bit…I don’t know, musty.

And I wondered, also, if the early ’90s collapse of Russian communism, which Reed cared about and worked for with such feeling in the late teens and early 1920s, has enhanced the film by making it seem more like a tribute to lost-cause Quixotic dreams, or diminished it because it Bolshevism (which the film portrays as being a brutal and failed system almost from the get-go) came to naught at the end?

I’d forgotten what a deeply annoying piece of work Keaton’s Bryant is — insecure, snappy, under-talented, ready to argue at the drop of a hat. She has an affair with Nicholson’s Eugene O’Neill and that’s…well, emotional indiscretions will happen every so often, but she walks out and all-but-terminates their relationship when Reed acknowledges he’s had a dalliance or two on the side and what-of-it?

Miller and Beatty had only met once before, but they seemed relaxed with each other. I liked Beatty’s observation that directing a movie was a bit like vomiting. “When things build up inside you eventually start to feel like vomiting,” he said. “You don’t want to vomit, but when you finally do you feel much better.” And I enjoyed a later moment when Beatty said to Miller, “You’ve acted, right?” and Miller, “What the fuck are you talking about? I haven’t acted since high school.” And also when Miller said, “You began filming the ‘Witnesses’ in the ’70s,” and Beatty replied, “The 1870s.”

Beatty mentioned during the q & a that his 12 year-old son Ben said earlier in the evening that he thought Reds was too long.

I spoke to Beatty this morning and asked him how Reed might have evolved in his thinking if he hadn’t died at such a young age, and what would he have said about the ultimate fate of Russian communism?

“I feel he wouldn’t have moved to the right [if he’d lived],” said Beatty. “And uhm…it’s very interesting. How some people moved from the far left to the far right, like Max Eastman. And you know, what happened to people during the Stalinist purges moved a lot of people to the right…and then there were a lot of people who didn’t. I believe Reed would have…well, of course, I don’t know…but I believe he would have remained true to that which he thought was workable. I also think he saw the upcoming problems with Communist dictatorship.”

Beatty said that he’d “he’d never taken DVDs seriously until now. I thought it was retrograde. I thought the picture is what it is and why excessively look back? I don’t feel that anymore because I think the nature of distribution has had a deleterious effect on certain content.

“This film, which cost $32 million to make…this film, Dr. Zhivago and Lawrence of Arabia wouldn’t and couldn’t be made in today’s environment — they wouldn’t be financed. Can you imagine anyone today putting $150 million or $200 million dollars into a story of a very strange Englishman who goes to Arabia, behaves peculiarly and dies on a motorcyle…and played by an unknown?

“DVD releases and the obviously long shelf life that comes with the DVD market are the replacement for the long theatrical life that films used to have in theatres, plus it saves the audience from having to experience the mall experience, which is largely a hormonal matter these days. The home screens are getting bigger” — Beatty has a high-def system in his home — “and the multiplexes are…well, the large theatres at the Arclight are more of an exception than the rule.”

Reds will be at the Arclight on October 13th, as well as at the City Cinemas Village East in Manhattan and the E Street Cinema in Washington, D.C., on October 6th.

“I’ve never before studied the [DVD] situation, ” said Beatty, “but with theatrical you sometimes have your film opening against four or five movies on the same dates. There are 117 other DVD titles coming out on October 17th.” Before he said that I had guessed there were probably 20 other recongizable titles coming out that day.

I don’t think anyone gives a damn about the other 100.

Reds is unusual in that it will be issued in three formats on 10.17 — on regular DVD and on both Blu Ray and HD-DVD high-def.