Suber Lesson #5: “There are three things that a memorable popular film is never about — (1) unrequited love, (2) impotence, and (3) despair. In real life, people experience unrequited love, impotence and despair all the time. But the gospel of popular entertainment is based on individualism” — the belief that you can become anything and anyone if your determination and inner resources are up to the task — “and anything that suggests otherwise is forbidden.”

Not literally forbidden, Suber is saying, but pretty much isolated, marginalized… barred from the realm of mass-acceptance. Which has nothing to do with critics and Oscar prognosticators admiring this or that film and running it up the flagpole, etc. I’m talking about the reactions of Academy members and Average Joe ticket-buyers.

As much as I admire Todd Field‘s Little Children for the craft and care that went into every aspect of it, and for the fully lived-in performances from Kate Winslet, Patrick Wilson, Jackie Earl Haley, Jennifer Connelly and Noah Baumbach, its conclusion delivers impotence (immature people unable or unwilling to stand up and grapple with serious personal issues that stand in the way of happiness and fulfillment) and despair (ditto) in spades. I saw it a second time last night and this fact hit me like a ton of bricks as I talked about it with journo colleagues in the New Line Cinema basement garage.

It saddens me to say this, but it’s inescapably true. This impotence-and-despair factor will probably block any Best Picture consideration as far as Little Children is concerned. The only real Oscar nom equation with any heat at this stage is Kate Winslet for Best Actress.

Roger Michell’s Venus, on the other hand, hits the trifecta — it’s about a very old man (Peter O’Toole) who has a bad case of unrequited love for a younger girl (who requites his feelings to some extent as the film moves along), plus he discovers that he’s literally impotent at the halfway point, plus he has periodic bouts of despair due to the inescapable fact that his life is near the end. And yet O’Toole’s desire to feel life coursing through his veins is strong and persistent throughout, and so the film finally is not informed or characterized by Suber’s three no-no’s as much as the spiritual negation of same.

DiCaprio for Best Actor?

“…then I realized, Gawd laeft this playce a lawwng time ago“…that’s Leonardo DiCaprio ‘s final line in the trailer for Ed Zwick’s Blood Diamond (Warner Bros., 12.15). This is being positioned by Warner Bros. as an Oscar-worthy movie, but The Last Samurai taught everyone that you have to be careful with Zwick. He can be tasteful and restrained at times, but also ham-fisted — for my money his emotional points have too often been underlined with a black felt-tip marker.

But the trailer tells me that DiCaprio — one of the three leads in Diamond, along with Djimon Honsou and Jennifer Connelly — is a strongly positioned Best Actor candidate. We all know that the Academy always responds to actors playing (a) handicapped characters, (b) characters with exotic accents (i.e., the Meryl Streep syndrome), and (c) characters that have required the actor to put on weight, wear a fake nose or teeth, or otherwise make him/her look less attractive than normal. DiCaprio’s South African accent in the trailer (which sounds pretty good to me — can any South African readers tell us if it sounds right to them?) indicates he’s definitely lived up to the Streep syndrome.

This means he’s on the brink of entry into the Best Actor finals if….if (and I can’t underestimate the importance of this qualification) Zwick’s film isn’t too Samurai– like. If Diamond turns out to be as compelling as it could be (it’s apparently an action-fortified moral tale about greed and redemption, set against the backdrop of the Sierra Leone civil war of the 1990s with DiCaprio playing a guilt-wracked South African mercenary), the combined heft of Leo’s morally-flawed-guy-who- becomes-a-man-of-honor plus his hard-punch performance as a mole inside a criminal gang in Martin Scorsese‘s The Departed could put him near the top of the heap and right up against Peter O’Toole (Venus), Forest Whitaker (The Last King of Scotland) and Derek Luke (Catch a Fire) and…who else?

I know, I know…Will Smith in The Pursuit of Happyness, right? But think about it — doesn’t Smith need to be bitch-slapped and kept down for playing the role of the rich, over-pampered movie-star smoothie and starring in Wild Wild West , Independence Day, Shark Tale and other such shite? Smith is a natural-born charmer with a gleaming smile who’s really good when he’s talking with Access Hollywood reps on the red carpet, and now that he’s shifting into major heart-tug mode in Happyness (and opposite his own son yet) we’re supposed to just topple …is that it?

“Flags” & Halbfinger

Clint Eastwood‘s Flags of Our Fathers (Dreamamount, 10.20), the WWII epic about Iwo Jima and the p.r. effort to celebrate the men who raised the flag atop Mt. Surabachi, began screening for selected journalists this week in New York, according to a 9.21 N.Y. Times piece by David Halbfinger.

He calls it “a big, booming spectacle that sprawls across oceans and generations,” with “much of [it] following the flag raisers as they crisscross the country in the spring and summer of 1945 pitching war bonds for a government in desperate financial straits. It is neither a pure war movie nor, given its sweeping and harrowing combat sequences, merely a wartime drama. It examines the power of a single image to affect not only public opinion but also the outcome of a war.

“Above all it is a study of the callous ways in which heroes are created for public consumption, used and discarded, all with the news media’s willing cooperation. And it is imbued with enough of a critique of American politicians and military brass to invite suspicions that Hollywood is appropriating the iconography of World War II to score contemporary political points.

“Yet just when it verges on indicting the people responsible for exploiting the troops, the movie comes round to their point of view.”

This last bit reads like a critique, no? Is Halbfinger saying Eastwood cops out or pulls his punches on some level? Left Coast critics and journos wll begin to see Flags sometime next week.

L.A. Nightscape

Looking south from building on the corner of Holloway and Alta Loma on Monday, 9.18, sometime around 10:30 pm or thereabouts. The last photo taken with my Canon Powershot A95 before it broke.

Paglia on Marie-Antoinette

Sofia Coppola‘s Marie Antoinette is a well made, relentlessly shallow film about an 18th Century Paris Hilton (Kirsten Dunst) living inside a whimsical fantasy membrane in and around the grounds of the Palace of Versailles in the years leading up to the French revolution. Camille Paglia is a brilliant writer, a social seer and a fearless pretense-puncturer, and she’s written a piece about…well, not Coppola’s film but how Marie-Antoinette is back in vogue. I was hoping she’d seen the film and might have hated it….pity. It is not enough to merely hate Marie-Antoinette. One needs to organize against it, storm its gates, demand that certain parties lose their heads.

Elton Brand and “Rescue Dawn”

ESPN’s “Page 2” writer Sam Alipour follows Rescue Dawn producer and Clippers All-Star hotshot Elton Brand around Toronto as he went to the premiere and the after-party and whatnot. If there’s a serious money quote in this piece, I haven’t found it yet. Maybe I need to read it again .

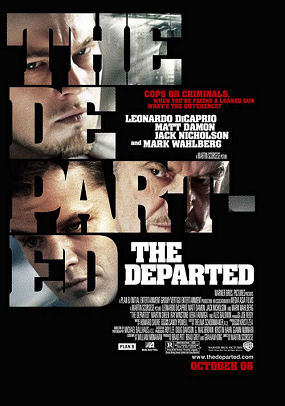

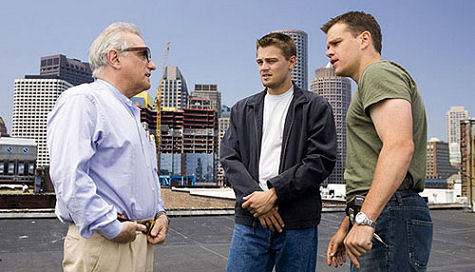

“Departed” transcript

Black Film.com’s Wilson Morales has transcribed what reads like a portion of last weekend’s Departed press conference. Matt Damon, Martin Scorsese, Leonardo DiCaprio, producer Graham King, Vera Farmiga and screenwriter William Monahan sat and suffered through a series of brain-novacaine press-junket questions.

“Babel” backlash?

A publicist I spoke to during a lunch earlier this afternoon told me that 80% of the “people” (journalists, I presume) she’s spoken to about Alejandro Gonzalez Innaritu‘s Babel have been iffy about it — too long, too much like the previous Innaritu films, etc. But there’s no basis for anyone to “meh” this film, I argued. It’s too well crafted, too full of feeling and echoes about parenting and children. Later I talked with an industry guy who’s spoken at length with Samuel L. Jackson, who saw Babel as a judge at the Cannes Film Festival, and the guy said Jackson felt that Babel is “Crash Benetton” — i.e., a European version of Paul Haggis‘s Best Picture winner. Dammit…that’s a ridiculous point of view. Babel may be in the same solar system as Crash, but it’s certainly not on the same planet. What the hell’s going on there?

Herron/Cooke/Thompson

FILMdetail’s Ambrose Herron on yet another anti-blogger screed written by a print journalist (the Guardian’s Rachel Cooke). Cooke’s piece was posted roughly three weeks ago (9.3) — why does it take people like Herron and Anne Thompson so long to respond to these things? Why am I posting this item myself? I don’t really give a shit about any of this. That’s not true — I do give a shit about some of it.

Life is duty

Suber Lesson #4: “In many of the most memorable stories, th central character is torn between desire and duty, between what the self seeks and society demands. The inner voice whispers, ‘I want…’ but the outer voice responds, with an echo-chamber resonance, ‘You must…’ The duty of the hero is not merely to stand up; he must stand for something. It’s not something he desires; it’s something he’s got to do.”

For some reason I’ve never forgotten this line from a David Mamet script for a 1987 “Hill Street Blues” epsode that he did a one-shot thing for: “I went to sleep dreaming life is beauty; I awoke the next morning knowing life is duty.”

Sven Kyvist is dead

Sven Nykvist, the cinematographer who shot Ingmar Bergman‘s best films with some of the most exquisite black-and-white compositions in film history, has died. I admired his color photography on Woody Allen’s Another Woman and especially Crimes and Misdemeanors, but deep down he will always be the silver-monochrome painter who shot Bergman’s The Virgin Spring, The Silence, Persona, Winter Light and Through a Glass Darkly. I met him on the set of King of the Gypsies in Manhattan back in ’78 or thereabouts. Sven was only 83 years old. He lived his last days in a Stockholm nursing home where he was being treated for(this is awful) a form of dementia called aphasia, according to Carl-Gustaf Nykvist, his son.

Scorsese Wired

Scorsese Wired

At long last and after weeks of conflicting buzz-hype, Warner Bros. finally had a screening last night of Martin Scorsese‘s The Departed (10.6), and what great Scorsese stuff it has. And what a relief! The fabled director of Mean Streets, Taxi Driver and Goodfellas is back on the contempo urban turf where he once belonged. Here, at long last, is a return to an old-school, brass-knuckles crime flick with piss and vinegar and style to burn. It may not be profound or symphonic, but it’s cause for real cheering.

Every piston in this film is well-oiled and chugs like a champ. The result is a package that’s violent as hell and smartly written (hats off to William Monahan‘s script, which is much more clearly written and easier to follow than Siu Fai Mak‘s 2002 Hong Kong thriller, which I got totally confused by when I saw it in Toronto four or five years ago), and is heavily pumped and beautifully scored (the sound- track is a well-chosen cavalcade of ’60s and ’70s tracks) and superbly acted by a live-wire, blue-chip cast.

And I mean especially by Leonardo DiCaprio, who hasn’t been this good since What’s Eating Gilbert Grape?. (I was going to say Titanic, but his work in that James Cameron film is so divorced from what he’s up to in The Departed that they shouldn’t be mentioned in the same breath.) I don’t want to get hung up on just DiCaprio here — this is a film that works because all the elements groove together just so, and Leo is only one of several — but it’s great to report that after two middling efforts (Gangs of New York and The Aviator) he and Scorsese have finally generated real electricity.

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

The Departed doesn’t exactly throb with thematic weight. It’s just a feisty, crackling crime film — a double-switch, triple fake-out dazzler about lies and cover-ups and new lies to take the place of old lies, and about the psychic toll of being a two-faced informer and living in a whirlpool of anxiety and dread. And it’s DiCaprio, more than costars Matt Damon, Jack Nicholson, Alec Baldwin or Mark Wahlberg or anyone else, who exudes the vibe of a hunted, haunted animal — a guy so furious and frazzled and inwardly clenched that he can barely breathe.

Don’t even talk about Leo’s Amsterdam Vallon in Gangs of New York or Howard Hughes in The Aviator or Frank Abagnale in Catch Me If You Can . In fact, some- body ask those guys to please leave the room and wait for us in the car. We’ll be out later.

I’m not sure that what DiCaprio does in this film amounts to much in terms of reflecting or expressing some great current in the human condition — he’s just part of a very tricky and feisty concoction here — but in the annals of crime-movie performances he knocks it out of the park. And I hear he’s knocks it hard and fierce in Ed Zwick‘s Blood Diamond also, so maybe he’ll wind up in the derby.

There’s no question — none whatsoever — about The Departed being Scorsese’s best film since Goodfellas. Is it as good as Goodfellas? Well, no…but who cares? It’s tight and trim and exciting at every turn. It may not “say” or mean a whole lot, but at least it’s Scorsese back in the groove.

It’s going to make a fair amount of money. The strongest demos, obviously, are going to be older and younger males, and there may be some who will feel that the ending is a little too bitter and apocalyptic (think Taxi Driver squared), but the word-of-mouth will trump this. I stil don’t get why Warner Bros. publicity decided to hide this film from the Toronto crowd — it would have been the toast of the festival and then some — and or least let some of us see it along with the junketeers who caught it during the festival, but whatever.

The energy, punch and Boston street funk in The Departed is so “on” and plugged in that Scorsese’s last sixteen years of creative striving falls into sharper relief after seeing it. Since the unqualified triumph of Goodfellas in 1990 the poor guy has been a good shepherd wandering in a desert — grasping, floundering, trying like hell to make a great film about something other than wise guys jousting and finagling on streetcorners.

Obviously Scorsese has done moderately well with other types of films but contemporary urban crime is his home ground. I’m sorry to be blunt about this, but the difference in focus and pizazz between The Departed and Gangs of New York, The Aviator , the cufflinks movie with Daniel Day Lewis and Kundun is just too glaring not to remark upon.

In the final analysis The Departed is just a brutally tough popcorn movie, but even as such it’s way more effective than Bringing Out The Dead, and it’s a much more riveting entertainment that Cape Fear or The Color of Money, even. It’s not a realstic film — Monaghan’s dialogue is stylized and snappy in a David Mamet-on-steroids way — and everyone is acting with some kind of Boston accent, but it’s all of a piece. And when something is this assured and well-fused, a lack of depth and thematic resonance doesn’t feel like a big hassle.

The Departed may just be a portrait of Marty pulling out the stops and resorting to every trick in the book to make this crime story “play” in a way that will make guys like me respond — it may have been made from a place of total cynicism and I don’t care. All I know is that the sputtering engine is back in tune again, and that it’s a joyous thing to be enveloped by a fast and flavorful Scorsese film that’s loaded with Boston “English” and plotted tight as a drum.

I guess I have to recite a plot summary of some kind. The story is basically about two moles — a “bad guy” (Damon) infiltrating the ranks of the Massachucetts State Police, and a “good guy” (DiCaprio) infiltrating Nicholson’s South Boston crime gang. Two rats, two wolves in sheep’s clothing…and sooner or later it’ll all come out in the wash. The key man in the middle is the burly and boodthirsty Nicholson, who obviously knows about Damon but doesn’t know about DiCaprio. Two guys with the “Staties” — Wahlberg and Martin Sheen — know about DiCaprio but are clueless about Damon. Vera Farmiga is a sketchily-drawn psychologist who has affairs with both Damon and DiCaprio.

How good is Nicholson? Great in terms of his usual presence and assurance, but it’s basically Jack playing off his legend rather than inhabiting a sadistic monster created by Monaghan (and allegedly based on a real-life Boston crime figure.) He basically tries a lot of stuff, and some of it connects and some of it is funny but it’s basically “okay, good old Jack, we love him…next.”

Every actor kicks ass in this thing — there are no “meh” peformances. Farmiga, Wahlberg, Alec Baldwin, Sheen, Ray Winstone and Kevin Corrigan are all great. I got a feeling from the print I saw last night that a lot of saucy stuff was left on the cutting-room floor so here’s hoping for a heavily loaded DVD in early ’07.

I’ve run out of things to say and I have to get to a luncheon, but what a great thrill it is to see a real Scorsese film again. He’s a great jazzman and impresario who knows the urban goombah thing up and down. He’s obviously been trying to duck this syncrhonicity for years, but he can’t. Marty may feel a wee bit unhappy about this on some level, but his fan base won’t be. Nobody will, really.