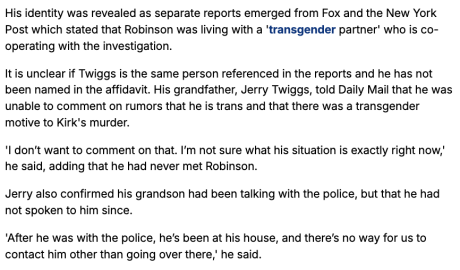

…and by “panning out” I mean if the N.Y. Times grudgingly admits down the road that Tyler Robinson‘s reportedly transgender partner Lance Twiggs, who’s reportedly been cooperating with the FBI, is in fact a transgender person….if it’s apparently a factual situation…if this is legtimately real-deal, the trans community will never wash this off.

It isn’t at all clear that the Robinson-Twiggs entanglement was romantic or merely a roommate arrangement, but it sure doesn’t look good, general impression-wise, for the trans community as we speak. If these reports really and truly pan out, I mean…if it all comes out in the wash.

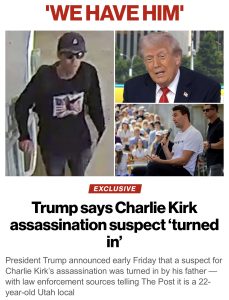

Various reports say that 22-year-old Twiggs is a biomale who’s apparently transitioning (or has transitioned) into womanhood. He and Robinson reportedly shared a three-bedroom apartment in the Fossil Hills housing complex in St. George, Utah.

Let no one dispute that Lance Twiggs is a great-sounding name for a young gay guy. Lance Twiggs could have been the name of a Times Square or Union Square hustler out of a 1969 Andy Warhol-Paul Morrissey film. If Twiggs, obviously quite attractive, had been around back then Morrissey would’ve definitely cast him in Lonesome Cowboys.

Trans-favoring Lefty Millennial: “One story says roommate, not partner. Right now this is rightwing bait for mouthbreathers such as yourself, desperate to assign trans people as the menace to society. Fuck off.”

HE: “You’re in denial, bruh. True, it’s mainly the conservative press reporting this story, but you can’t be thinking this is total poppycock. The Daily Mail has apparently done some real reporting.”

Trans-favoring Lefty Millennial: “You’re a bigot. You’re part of the problem.”

HE: “I’ve never vibed any trans people with hate or bigotry. EVER. I’m a turn-the—other-cheek kinda guy. Comme ci comme ca. Don’t judge, go easy. But these reports are social cancer, if true.”

Trans-favoring Lefty Millennial: “You’re full of shit. You’ve been filled with hate since your life blew up.”

HE: “I wasn’t cancelled by transies. I was cancelled by revenge-minded female publicists and certain female journos. I was cancelled by a #MeToo hit squad. Without my having said or done anything actionable.”

Trans-favoring Lefty Millennial: “Blocking this convo. Keep this filth to yourself.”

HE: “The side that shoots someone in the neck is the side full of hate…I think that’s fair to say.”