[WARNING TO SPOILER WHINERS: I decided not to bypass a certain fascinating plot point in Phantom Thread, and so at the very end of this review there are SPOILERISH observations. If you want to steer clear of the spoiler stuff, read the first 20 graphs and let it go at that. Don’t read the six-paragraph section titled THERE WILL BE SPOILERS. Do the first 20 and you’ll be fine.]

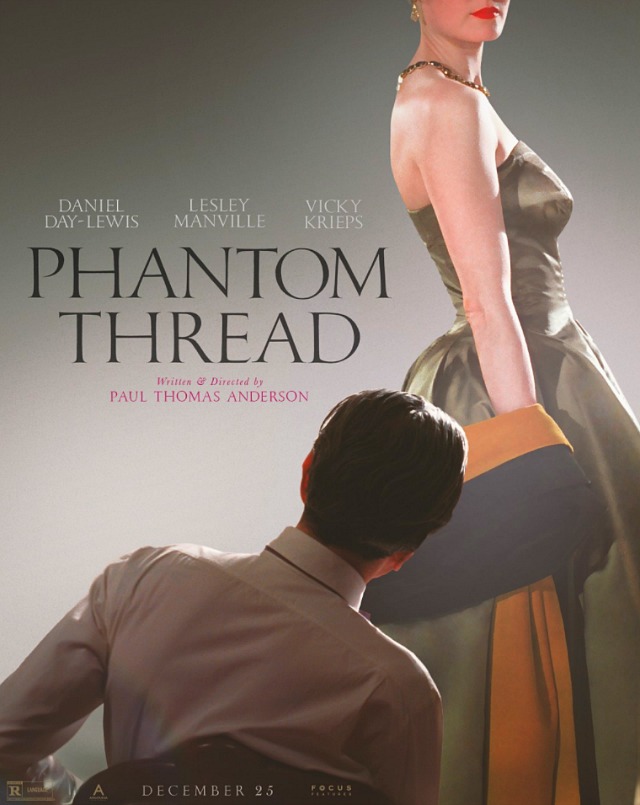

Paul Thomas Anderson‘s Phantom Thread (Focus Features, 12.25) is a first-rate parlor drama about some very exacting and demanding Type-A people — three, to be exact — going to war in mid 1950s England. Indoors, I mean. And very methodically.

It’s an absorbing, brilliantly refined drama about a bad marriage, which is to say a marriage made in hell, which is to say a marriage that should never have happened save for the influence of Satan. As with all marriages, it leads to a ghastly struggle of wills and finally, after the last futile drops of resistance are spent, to surrender on the part of the husband.

This hellish union happens because Daniel Day Lewis‘s Reynolds Woodcock, an elite London couturier (i.e., a fashion designer who makes and sells elegant clothing to rich clients), doesn’t know himself, and so he attracts and then entices Alma (Vicky Krieps), a young, off-pretty waitress, to be his lover and collaborator and eventually his wife. Woodcock thinks he’s “in love” but he really wants his dead mother to come back to life and take care of him.

The problem is that Woodcock, aided and abetted by Cyril (Lesley Manville), his Mrs. Danvers-like sister and business manager, is a control freak who doesn’t want anyone interrupting his work regimen, which is very strict and exacting. The other problem is that the willful and opinionated Alma wants what she wants. The final solution to this horrific power struggle is, of course, capitulation.

Phantom Thread is, no question, a very well-made PTA film, adult and dry and precisely measured. And decisive. I liked it enough to see it twice, and I enjoyed it a lot more than Anderson’s relentlessly hateful Inherent Vice, and I came to understand it better than The Master, which I loved for the eccentric chops but which finally left me with “what the hell was that all about besides a Scientology tale?”

And yet Phantom Thread is rather modest in scale. Two sets — a London townhouse and a country house — and three characters, and all of it about whether Alma will do Reynolds’ bidding or vice versa.

It’s very well composed, in short, and perfectly acted. But slow as molasses. Not a “date movie.” Not a thriller. Basically a perverse film about who gets to run the marriage. It’s an allegory about that. A little bit like Darren Aronofsky‘s mother! in a way, although in this scenario the wife isn’t roasted alive and an infant child isn’t passed around and devoured by a mob.

Critic friend (used with his permission): “A fascinating, infuriating movie. At one point I thought, ‘Hmmm, he wants to make a Todd Haynes film.’ Which, in a way, he has.

“I will say I liked it better than The Master or anything he’s done since Magnolia. He always strikes me as a perverse filmmaker, teasing the audience with the sense that something else is going on without ever really getting down to it (perhaps because there is no THERE there in the writing after all). I also hate how he uses Johnny Greenwood‘s music to build tension when the scene itself has no obvious source of tension other than the music.

“I personally loved the give-and-take scenes between Reynolds and Alma and Reynolds and Cyril; all that repressed emotion behind witheringly cutting lines. The audience I saw it with laughed loud and hard at some of that stuff, as though it were a drawing-room comedy, which seemed strange. Oscar Wilde-ish Phantom Thread‘s dialogue is not; what dark humor there is lies in the acting, rather than the writing.

“It’s always fascinating to watch DDL work because he’s so good. But you feel the effort more when the material is as thin as this. Vicky Krieps looks a bit like Meryl Streep circa Sophie’s Choice. In the end the film doesn’t pay off, emotionally or dramatically. But that’s never been what Anderson’s films are about. He seems to purposely avoid anything that would gratify any audience member in an obvious way.

“An audience film immediately announces what it’s about, tells a linear story with characters who are not only easy to understand and identify with but who make you eager to root for them. Audience films invite you in, show you around and make you comfortable so that you always know where you are. The Post is a good example of a well-made audience film.

“Critics’ films make you come to them. They challenge you to essentially jump aboard an already moving train and figure out where it’s going. The best critics’ films pay off that bet for audiences who believe the critic and take the challenge; the worst critics’ films (like The Master) have champions who make you believe there’s more than meets the eye here when, in fact, it’s all in their film-theory-addled imaginations.

“I believe this film falls into the latter category: It is the kind of film that makes people hate the critics whose reviews convince them to see it. This one isn’t as opaque as most of his films, but it makes you work harder than the average moviegoer wants to work. I see it sinking out of sight almost as soon as it it’s released, with perhaps critic-award nods for Lesley Manville.

“As for the Hitchcock stuff, again, it’s all misdirection toward some larger illusion that this guy has made a coherent, involving film. I was never bored. But I was also never satisfied.”

Another friend: “Phantom Thread is something of a question mark. Anderson’s words, complicated and peculiar, are effective and appropriate for the kind of slow-paced film that Phantom Thread is but…”

Friend: “Some of the writers were complaining post-screening about how slow and boring the film was. So it’s not just the Walmart crowd that will find it to be an endurance test. I didn’t find it to be dull at all, mostly because PTA always seemed to be one step ahead of us throughout. I really didn’t know where it was going, but, yeah, it’s still a fairly conventional film for PTA, a sort of 1950s gothic romance. It has none of the bold visionary markings of There Will Be Blood or The Master, but it’s nonetheless the work of a fascinating filmmaker.

Me (responding): “After the first screening a guy in our audience asked PTA the following: ‘I want to put this as respectfully as possible, but when you make your films do you do so with an interest in getting the best reviews or in hopefully exciting the interest of average ticket-buyers? Or do you just make them to satisfy yourself and come what may on the critical or commercial front?’

“The guy was obviously saying that he found Phantom Thread neither critically intriguing or a film with a great commercial future. He was wondering why PTA makes films that are this confounding and frustrating, or words to this effect. He was obviously struggling with his reaction.

Friend: “Daniel Day-Lewis is stellar as always. Lesley Manville is pure evil incarnate. Dare I say she delivered a better performance than DDL? And I really loved Vicky Krieps. You could totally understand why Woodcock would fall under her spell.

Me (responding): “Evil incarnate”? Manville just wants to keep the business going, avoid emotional tempests, protect her brother’s process, make sure the dresses get made properly, etc. Where’s the evil?”

THERE WILL BE SPOILERS: There’s a certain substance that is used in Phantom Thread in order to achieve a certain end result. I won’t say who uses it or what the substance is, but the substance in question is a symbol for whatever controlling tactics or strategies that wives come up with. The most interesting scene is when a certain party decides to accept the substance in question by allowing it into his/her system. He/she submits, in short, but with an expression that says ‘okay, fine, you got me….happy?’ He/she isn’t pleased with this submission, but he/she knows he has to give in to get what he wants — a maternal feeding and nurturing, what he got from his mother and still very much needs. Feed me, take care of me, nurture me, envelop me.

The last line in the film, a scene between Reynolds and Alma, is spoken by Daniel Day Lewis: “I’m hungry.” Their first scene together is also about his hunger — Welsh rarebit, sausage, a not-too-runny egg, bacon, toast, jam, etc.

BIG SPOILERISH: Imagine that classic image from Hitchcock’s Suspicion of Cary Grant ascending a staircase as he carries a curiously glowing glass of poisoned milk atop a silver tray. Compare the import of this scene, and recall how it ended in the original source novel (Anthony Berkeley’s “Before The Fact”) with Joan Fontaine‘s character knowing what was in the milk but submitting to Grant’s will regardless.

Hitchcock didn’t film this ending, of course, but what if he had? It wouldn’t be all that different from the ending of Phantom Thread. The victim knows that the mate wants control and is demanding submission, and so the victim goes along with it — you win.

This movie is a muted primal scream…a howl of male anguish and gut-level outrage about what a traditionally successful marriage essentially requires, and what a grueling battle it is to get there. If the wife wins, the marriage works. If the husband refuses to submit the marriage will not last. In the end the artist-husband submits to her nurturing instinct, to her need for maternal control. It’s a kind of step-by-step ritual, a de-balling process ending on bended knee.

Imagine the reaction if PTA had made a Phantom Thread with the story and roles reversed.

What if it was about a woman who was a dynamic artist-creator, an artist deeply and obsessively wedded to her work and her daily disciplines. One day she falls into an affair and then a marriage with a strong-willed guy who respects her creative output but who mainly wants her for his own reasons and primal needs? A man seeking, let’s say, someone sexually submissive plus a traditional maternal care-giver and homemaker? A man who not only seeks to dominate and control but uses a CERTAIN SUBSTANCE to mold her into a less obsessive, less creatively-driven artist and into more of a submissive sex kitten who will give him what he wants.

Imagine the reaction! This Phantom Thread would be ripped, vivisected and roasted alive by the femmebots.