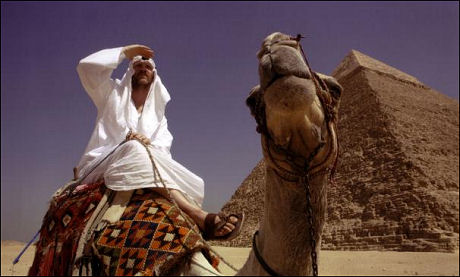

The three strongest impressions I have about Morgan Spurlock‘s Where In The World is Osama Bin Laden? (Weinstein Co., 4.18) are, in this order, trivial, critical and philosophical. I’m not afraid of admitting to trivial concerns, in part because I also know a worthy belief (or hope current) when I hear it.

Impression #1 is that since the Super-Size Me days, Spurlock has become super follically challenged and needs to talk to the Hair Club for Men. Impression #2 is that the tone of most of the film is way too flip and dumbed-down — it seems aimed at the dumbasses who wouldn’t want to watch a film about the east-west cultural divide and the nature of Islamic anti-U.S. fervor unless the filmmaker uses a chuckling whimsical tone and tosses in a few jokes. Impression #3 is that the final few minutes of Spurlock’s film say “the right thing,” which is that we need to try to find our common humanity and build whatever bridges we can, and to do that we need recognize the purist crazies in our respective cultures and isolate them.

This gives me a chance to talk again about Adam Curtis‘s The Power of Nightmares, which articulates the third point in a much more profound and penetrating way than Spurlock’s film does. Anyone who hasn’t seen it, whether they go to Spurlock’s film or not, needs to do so. It’s easily downloadable right here.

I wrote about it three years ago. “This new three-hour doc weaves together all sorts of disparate historical strands to relate two fascinating spiritual and political case histories, that of the American neo-conservatives and the Islamic fundamentalists,” I said. “The payoff is an explanation of why they’re fighting each other now with such ferocity (beyond the obvious provocation of 9/11), and why the end of their respective holy war, waged for their own separate but like-minded motives, is nowhere in sight.

“That’s right — the Islamics vs. the neo-cons. You might think the United States of America is engaged in a fierce conflict with Middle-Eastern terrorists in order to prevent another domestic attack, but what’s really going on is more in the nature of a war between clans. Like the one between Burl Ives vs. Charles Bickford in The Big Country, say, or the Hatfields vs. the McCoys.

“It’s not that Curtis’s doc is saying anything radically new here, certainly not to those in the hard-core news junkie, academic or think-tank loop, but it makes its case in a remarkably well-ordered and comprehensive way, which…you know…helps moderately aware dilettantes like myself make sense of it all.

“The film contends that the anti-western terrorists and the neo-con hardliners in the George W. Bush White House are two peas in a fundamentalist pod, and that they seem to be almost made for each other in an odd way, and they need each other’s hatred to fuel their respective power bases but are, in fact, almost identical in their purist fervor, and are pretty much cut from the same philosophical cloth.

“It says, in other words, that Bush, Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld and Paul Wolfowitz have a lot in common with Osama bin Laden. It also says that the mythology of ‘Al-Qeada’ was whipped up by the Bushies, that the term wasn’t even used by bin Laden until the Americans more or less coined it, and that the idea of bin Laden running a disciplined and coordinated terrorist network is a myth.

“Nightmares doesn’t trash the Bushies in order to portray the terrorists in some kind of vaguely admiring light. It says — okay, implies — that both factions are too in love with purity and consequently half out of their minds.

The three chapters are titled Baby, It’s Cold Outside (about the growth of both camps from the `50s through the `80s), The Phantom Victory” (about the Reagan years and how the Neo-Cons and the Islamics got together in battling the Russians during the Afghanistan War) and Shadows in the Cave (about how things have gone from 9.11 until the present).

“This conclusion leaves us with a feeling that we ought to stand up and act like good reasonable Gregory Peck-styled liberals and separate ourselves from these guys and their nutbag holy war, and maybe send the Islamics and the neo-cons off to a desert island and let them fight it out alone with clubs and knives.” This is almost precisely what Spurlock says at the finale of Where in the World is Osama bin Laden?. minus the desert-island idea.

“The neo-cons and the Islamists ‘believe that the main problem with modern society is that individuals question everything,’ Curtis told a reporter for London Time Out last October, ‘[and] by doing that the questioners have already torn down God, that eventually they will tear down everything else and therefore they have to be opposed.’

“In other words,” I wrote, “these camps are both enemies of liberal thought and the pursuit of personal fulfillment in the anti-traditionalist, hastened-gratification sense of that term. They believe that liberal freedoms have eroded the spiritual fabric that has held their respective societies together in the past. Curtis’s doc shows how these two movements have pushed their hardcore agendas over the last four or five decades to save their cultures from what they see as encroaching moral rot.

“I genuinely feel that Curtis’s film is more wide-ranging and sees right into the heart of these warring ideological beasts in a much sharper and more revelatory fashion than Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11.

You will probably never see this doc on American broadcast television and perhaps not even on any U.S. cable channels, but there’s something about Curtis’s pointed, relentless and irreverent British perspective that seems to cut right through the cobweb of our perceptions and draw a bead on what’s really happening.”