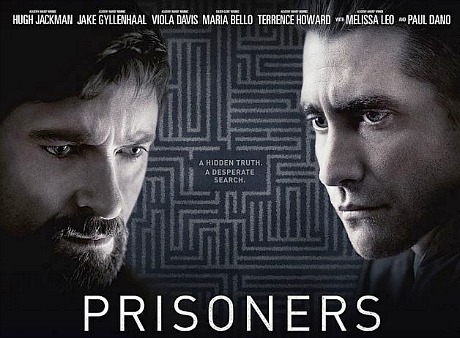

I recognize that Denis Villeneuve‘s Prisoners has won the devotion of the elites. I recognize that the damp, sprawling Fincher-like aspects of the damn thing are very appealing to a certain breed of critic. But for me and others in my aesthetic realm it feels more like a dense slog than anything else, and I think it might be nice at this juncture to gather all the complaints (like the 153-minute length and that “what?” ending) under one umbrella and kick the can around. All I know is that I began looking at my watch around the one-hour mark. All through Prisoners I felt weary and chilly and fatigued. “If this is such a good film — and it is — why do I feel like a prisoner myself?,” I muttered at one point.

Time‘s Richard Corliss acknowledges that while Prisoners “has more pedigree than a Westminster dog-show winner, it’s just not very good. In fact, it’s worse than not-very-good — it’s could’ve-been-really-good-and-isn’t.”

Christian Science Monitor critic Peter Rainer is saying that “for all its pretensions and intermittent power, Prisoners is essentially high-grade claptrap.”

Television With Pity‘s Ethan Alter has written that “when you finally emerge from your two-and-a-half hour sentence watching this glum, overbearing movie [that confines us to] a hellscape of strip malls and split-level homes, you’ll relish the sweet taste of freedom, too.”

Detroit Metro Times critic Jeff Meyers says the following: “Under cinematographer Roger Deakin’s masterful lens, Pennsylvania is a dark and rainy gloomscape where it seems the sun will never shine. The A-list cast grieves and rages with Oscar-baiting gusto, while Aaron Guzikowski’s triple-twist script navigates its labyrinthine (and ridiculously unlikely) criminal events and the actions of its irrational characters with confidence and conviction.

“Unfortunately, the directorial instincts of Villeneuve (a Francophone director in his English-language debut) lean toward the lurid, though he seems to think he’s making a grand and brooding statement about the human condition. [But] instead of emotional profundity or nuance, Prisoners gives us two-and-a-half hours of misery, grief and raw desperation in service of a trashy, manipulative script that craftily delivers a series of jolts and surprising reversals.”

One of my Telluride observations: “Aimed more at critics than ticket buyers, Prisoners is one of those melodramas that elitists love for the dank look and murky vibe and sprawling aroma, and which isn’t about catching the proverbial bad guy as much as meditations about (a) the evil in everyday life, (b) the high cost of vengeance and (c) how so much of life is a maze of false leads leading to a series of cul-de-sacs.”

I know what you’re thinking — how exactly does an aroma sprawl?