Puck Everlasting

The movies that seem to grab me the most are the ones that ask us to consider the mystical, the undefined, the intangibles…the ones that say “look up, look out, look beyond…there’s more to this world than what you can own, eat, taste or feel.”

The latest film to do this kind of thing well, and frankly one of the more interesting, amusing and affecting films I’ve seen over the last few weeks (if you don’t include An Inconvenient Truth, that is), is a new documentary about a bunch of guys who love to play air hockey.

Atypical action moment in Eric D. Anderson’s Way of the Puck, meaning that 98% of it was shot in regular color video.

It’s called Way of the Puck — and no one anywhere has seen it, except for a handful of film festival programmers. It’ll be having its world premiere at Houston’s Worldfest Film Festival in mid to late April.

I’m not saying it’s wet-your-pants fantastic, but if you can imagine something as arcane as a thinking man’s air-hockey film…one that doesn’t so much focus on a stupid plastic puck getting knocked back and forth by a couple of guys leaning over a gleaming blue plastic surface as much as…well, the zen approach to this simple-ass game, keeping a light touch, concentrating hard and yet not concen- trating as much as feeling the force…this is it.

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

The “maker” is Eric D. Anderson, a Los Angeles-based guy who works on music videos and commercials and has spent the last two-plus years putting this doc together, partly (as you might expect) because he’s a big air hockey nut himself, but also because he sees a Great Beyond inside it…a world within a world.

“On the surface air hockey seems like a story with very low stakes,” he writes on the film’s website. “Or no stakes at all. I get a lot of this. ‘Air hockey?’ people say, nodding slowly. ‘That game from the ’70s? Hunh.’

“Air hockey isn’t the unpopular kid who gets kicked around at recess.

Air hockey is the kid no one notices, including the teacher. It’s a forgotten arcade game, a kid’s game, a relic, a jobby, a diversion, a trifle…and what could be less important than that?”

But in the making of this film, says Anderson, “I discovered a passionate and intelligent community of players. These are underdogs, participating in a fringe sport. They know they are dismissed and sometimes mocked and that air hockey will proably never be accepted by the mainstream. And yet they continue to travel thousands of miles to compete against the best players in the world.”

Way of the Puck is a guy film, mostly, obviously, but a smart one. Alert, spiritual, philosophically loaded. “Small” and a little familiar in certain ways, maybe a tiny bit repetitive (and maybe a little long…just a wee bit) but within its own territory it feels solid and connected and complete.

It’s a real middle-class film about a gaggle (somehow that word feels right rather than ‘group”) of five or six American middle class guys, most of them married and either pudgy or bearded or balding (or all three) who are serious air hockey freaks, and who all happen to be quite thoughtful and intelligent.

That’s the first big revelation — air hockey doesn’t seem to be played by meatball blue-collar types but by unusually bright and creative guys. Or so this film implies.

Eric D. Anderson

These aren’t exactly rugged individualists, but guys with a certain consistency and tenacity. Not the kind of men whom anyone would call intense or magnetic or start- ling, but men with an undeniable passion and dignity. And maybe a certain sadness or resignation thrown in, marital responsibilities and the day-to-day slog being what they are.

And yet they share an obvious, unshakable, undeniable belief in air hockey as some kind of transcendent pursuit…something that sustains their spirit, gets them through the rough patches, puts a special kind of English on their existence, makes life feel whole (or at least gives it a certain weight and dimension) and worth living.

More so from the audience perspective because air hockey isn’t that recognized or celebrated…far from it…but it’s their own thing, played as it is in those little rooms, and they’re happy with that. Or happy enough.

And there’s that cool robot. A one-armed guy resembling one of those Empire droids in Attack of the Clones playing a pretty good game of defensive air hockey with very some very fast reflexes. I’ve only seen human-sized robots with arms and legs do things like walk dogs and vacuum rugs. This guy’s different. Impressive.

Robot air hockey

The point of Way of the Puck is that an air-hockey player needs to be alive and alert and in touch with something inward and flowing to get anything out of the game. More than just a fast hand and a light touch, but man…that robot.

Anderson believes that air hockey is “the culmination of 2500 years of human thought — connected to astronomy and artificial intelligence, music and missiles, comics and country + western dancing, painting and punk rock.” I don’t know if I can go that far, but Way of the Puck convinced me that air hockey amounts to something, or at least the players do.

Memory Lane

April has barely begun and the media drumbeat over the year’s two big 9/11 films, both produced with the upcoming five-year anniversary in mind, is already pretty loud.

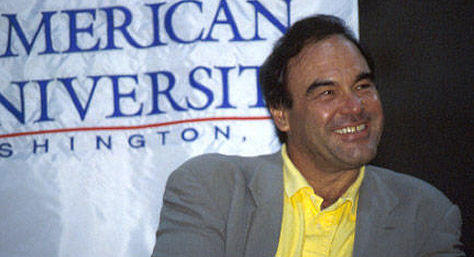

Press screenings for United 93 are beginning this week, stories attempting to gauge the public’s interest in seeing this and other 9/11 presentations are running (the Wall Street Journal and Newsweek ran theirs on 4.7 and 4.10, respectively), and we’ll be hearing more and more about Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center next month when a 20-minute reel from the 8.11 Paramount release is shown at the Cannes Film Festival.

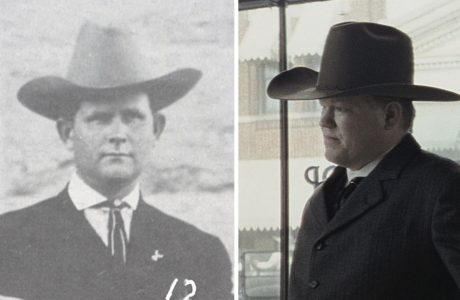

Nicolas Cage as Sgt. John McLouglin in Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center (Paramount, 8.11)

The 9/11 anniversary isn’t for another five months, of course, but I’ve been thinking about another startling event that happened in Manhattan nearly five years ago — a panel discussion on Saturday, October 6, 2001, at Alice Tully Hall called “Making Movies That Matter: The Role of Film in the National Debate.”

I reported on this right after it happened and I’ve mentioned it since (most recently in a WIRED item around noon on Sunday, 4.9), so why dredge it up for the third or fourth time? Because what panelist Oliver Stone said that day is, to me, still bang -on-the-head thrilling, and I’ve been wondering what’s changed in the four and a half years since…if anything?

It’s Sunday, it’s sunny outside, birds are chirping and I’m just going to run this piece again. (Most of it.) It’s a portrait of what’s been happening in this town for a long time, but the precision and candor in Stone’s rant still resonates.

Stone tried to describe the mindset and inclinations of corporate-run Hollywood as he saw it back then. Has the situation abated, remained the same, gotten worse or what? Read this through and think about it. I’m asking.

I’m repeating what I said in the WIRED item, but this sure was a long time ago, especially considering the apparent repositioning that has happened inside Stone himself, who was obviously more than a bit of a firebrand on 10.6.01 and now look at him, the director of a 9/11 pic about a couple of Port Authority guys who got buried under the fallen towers…a film that’s starting to sound, frankly, like it may be a head-in-the-sand emotional comfort blanket disguised as a rescue thriller.

Before the ’01 debate: Lumumba director Raoul Peck, essayist Bell Hicks, director Oliver Stone, New Line Cinema honcho Robert Shaye, political writer Christopher Hitchens, former Universal Pictures chairman Tom Pollock, indie producer Christine Vachon (Boys Don’t Cry, Storytelling), former Universal Pictuers chairman Tom Pollock (almost completely hidden), and HBO executive Colin Callender.

I’m not saying World Trade Center won’t be a well-crafted or emotionally affecting drama. (Alexander aside, Stone is still a top-notch filmmaker). And who knows? Maybe it will contain echos and undercurrents that will add dimension to what screenwriter Andrea Berloff believes it is (“a boy-down-a-well saga’). But read the following and tell me Stone hasn’t trimmed his sails just a tad.

“Say what you will about Oliver Stone’s political views, but he’s a master at whipping up a crowd,” I began. “This was plainly evident during a panel discussion he participated in last Saturday at New York’s Alice Tully Hall called ‘Making Movies That Matter: The Role of Film in the National Debate.’

“The same brio that has enlivened many of Stone’s politically driven films, including JFK, Born on the Fourth of July, Platoon, and Nixon, was in full force during the sometimes brawl-like, HBO-sponsored discussion.

“Stone’s chief nemesis during the discussion — which also included some volleys from from political writer Christopher Hitchens, former Universal Pictures chairman Tom Pollock, indie producer Christine Vachon (Boys Don’t Cry, Storytelling), Lumumba director Raoul Peck, and political essayist Bell Hooks — was New Line Cinema chairman and CEO Robert Shaye.

“It fell to Shaye to articulate the status-quo views of corporate Hollywood, which elicited not only the wrath of Oliver but occasional groans from the audience. Much of what Shaye said was fair and sensible, but it was no match for the sweep of Stone’s oratory, which occasionally vaulted past the concerns of the entertainment industry to include speculation on the whys and wherefores of the 9/11 disaster.

“The central issue was whether Hollywood’s increasing reluctance to finance films with a strong political undercurrent (particularly in the wake of the World Trade Center attack) was being caused by a corporate-driven aversion to anything that isn’t essentially banal or superficial, as Stone asserted, or whether the main impediment to the funding of risky and/or controversial films is ‘the tyranny of talent,’ as Shaye put it, referring to astronomical fees demanded by actors and certain high-profile directors.

“Stone launched into one of his hardest-hitting points by recalling the relatively modest financing that gave birth to Born on the Fourth of July, his Oscar-winning 1989 drama about Vietnam veteran Ron Kovic that starred Tom Cruise.

“‘We struggled to make it,’ said Stone. ‘We had fights. The picture cost $16 million, and then it went to $17 or $18 million, and we fought for that extra two million like crazy.

“‘But this was 1989 — and there’s been no significant inflation in the United States since then,’ he continued. ‘Why, in 2001, does a picture that was done very tightly in 1989…[would] that picture today cost $60 to $80 million? With the marketing costs added in, which are inflated, putting it into the $90s…advertising and television…we’re talking a $100 to $135 million event.

“‘This would no longer be a movie, but an event. And someone like Tom Pollock would say…’Born on the Fourth of July? I’m not going to make that for $130 million!’ Because [this kind of film] can’t work any more in a system that has gone bananas .’

Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall

“Stone was greeted by a passionate, sustained round of applause. Who doesn’t feel that films like Born on the Fourth of July, for which Stone won a Best Director Oscar and Cruise was nominated as Best Actor, are in woefully short supply these days?

“‘And this ties in to the Arab situation,’ Stone went on. ‘Why have we gone, in a non-inflationary era, to a [place] where our corporations have become huge over the last 10, 12 years? We’ve let them go. There’s been no trust-buster around. Teddy Roosevelt is long dead. And these media corporations have conglomerated themselves into six principal fiefdoms run by barons…they’re bigger than barons. They’re kings.’

“Stone was referring to Sumner Redstone who runs Viacom, which owns Paramount; Barry Meyer of Time-Warner, which owns Warner Bros. and New Line Cinema; Rupert Murdoch of Fox Newscorp., which runs 20th Century Fox; Mel Harris of Sony Pictures; Michael Eisner, the chairman/CEO of the Walt Disney Company; and Jean-Marie Messier of Vivendi, which owns Universal Pictures.”

[Note: Today’s media barons are Viacom’s Redstone, Newscorp’s Murdoch, Richard D. Parsons of Time-Warner, Sony Corp.’s chairman and CEO Howard Stringer, Disney CEO Bob Iger and Jeffrey R. Immelt, CEO of General Electric, which owns NBC Universal.]

“And these six companies decide,” said Stone. “Rupert Murdoch says ‘I would not make JFK,’ or Mike Eisner says ‘I would not do a film on Martin Luther King, Oliver, [because] there’s gonna be rioting at the gates of Disneyland’…you know, this is bullshit!”

“Gales of applause greeted this one, with some scattered yelps and cries of ‘right on!’

“‘These six people have control of the world and that’s what the new world order is,’ he explained. ‘Six men are deciding what you’re seeing in film, and they own all the small companies…it’s hard to find one that’s not owned by one of these huge companies buying new companies, so it’s a dilemma. There’s a control of culture, ideas, everything.

“Now, within reason, they let [filmmakers] do certain things, and that is far better obviously than, say, the Arabs where they don’t let you do anything, and I agree it’s relative. But we are in a dilemma. We have too much order.”

“‘And I think the revolt on September 11 was about order,’ Stone went on. “It was about fuck you, fuck your order…it was an eruption of rage about this. And is it time perhaps to reconsider the world order? Is it time to wonder why the banks have joined the movie companies and all the corporations, and where this is all going?”

“Hitchens, who writes for The Nation and Vanity Fair , bridled at the use of the term ‘revolt’ and said the September 11 massacre ‘was not a revolt. It was a state-supported mass murder using civilians as missiles. It was an attack on civil society and civilization.’ This drew vigorous applause, albeit slightly more subdued.

“Shaye said, ‘I disagree with Oliver about this. I think he’s talking about an era and the studio system of 30 years ago. I will tell you, and Tom Pollock will back me up on this, that this is a tyranny of talent right now, and I don’t know what Oliver gets for directing a film, but I know what a lot of other people get, and it’s way too much. I do know that the last guys to get paid, believe it or not, are the studios that put up the money, and…’

Robert Shaye (r.), co-chairman and co-CEO of New Line Cinema (pictured with Michael Lynne (l.)

“At this last remark, Stone shuddered and flopped back in his chair and looked up at the ceiling as if to say, ‘Did he just say that? I give up!’ Torrents of laughter. The hall was jumping.

“‘And if there’s a tyranny, it’s a tyranny of talent,’ Shaye concluded, drawing muted sneers and guffaws.

“Pollock, who was running Universal’s movie division when Born on the Fourth of July got made, said the go-ahead happened ‘because Oliver Stone was willing to make it for no money, and Tom Cruise was willing to make it for no money. The film was successful, they made a lot of money, and so did Universal, but it would not have been made had they not done that.

“‘Controversial films can still get made,’ said Pollock, ‘but films cost what they cost because most of the people who make them want to get paid as much as they can. They want control, but there is still that trade-off of money for control. We are in an oligarchy now where the large companies control what we see…yes, Rupert Murdoch has a political agenda, but by and large Rupert Murdoch is only interested in money.

“‘The problem with the six guys running the six companies is, they want to take no risks at all,’ he concluded. ‘They want movies that entertain only, if they can be marketed. There was little room before September 11 to make political movies inside the system. There’s less room now. It isn’t that it’s not going to happen. But it is going to be harder. And to that extent, Oliver is right.’

“Shaye said that New Line Cinema ‘started out in my apartment on 14th Street. We made our way in the world. We started out with Sympathy for the Devil. Talk about political…give me a break. And you know why it made money? Because the Rolling Stones were in it, not because Jean-Luc Godard had anything particularly profound to tell the world.’ Random hoots and snorts greeted this one.

“‘It’s a little disenchanting,’ Shaye continued. ‘The truth of the matter now is, right now, that with high-definition and video and stuff like that you can make a good movie for not very much money. The great thing about the entertainment business and the movie business is that when a movie’s good, you attract people. People talk about it, the whole word-of-mouth thing…the quality of a movie is a self-fulfilling mechanism.”

“Stone jumped back in. ‘Thirty years ago, Bob said before. That’s when he got started. It was all…it was another world. [But] nobody here has answered that question why, between ’89 and 2001, everything has become so uniform…what’s basically happened in the last 10 years is that the studios have bought television stations. And why?’

“Referring to the so-called ‘syn-fin’ legislation passed under the Clinton administration a couple of years ago that allowed studios to own more TV stations, Stone asked, ‘Why did that telecommunications bill get passed at midnight? It was basically a division of the world by a few media moguls and it was a giveaway and it was done at midnight and it’s a disgusting thing. To own TV stations is the basis upon which movie companies today have to exist. And that’s changed everything. There are only so many television stations. Each one has their big build-up and that’s their base of operation.

“‘And Bob [Shaye] knows it because he sold his little movie company to Warner Bros. for more money than I could ever dream of making,” Stone continued. He acknowledged that certain high-profile directors, such as himself, are well paid for helming big-studio films. But the majors these days “don’t need a top director, they feel. Just make the movie. Because for them it’s all about marketing and about subject. That’s what they think.

“‘So there’s no ‘left’ point of view. It’s not financially interesting for them to make a movie with a director who costs more money…they’d rather go with a marginal director. It’s all about product…movie product…and it’s all about this new world order.

“‘And the Arabs have a point. Whether it’s right or wrong, there’s an objection to the way the world is going. There’s a lot of hate and revolt in that state. It may continue and although the shoe may drop on the other foot the next time, the point is they’re objecting to something. And I say that we’re not dealing with that objection on this stage today. There was a breakdown in the ’90s, in the system, the world system, the world banking system…it’s the new world order, and it’s about order and control, but this control comes with a cost.

“‘One of the most banal ways for censorship to operate in America,’ Stone continued, ‘is to drive out thought by explosions of People magazines and celebrity culture and…our culture is focused on Sarah Jessica Parker and kind-of inane, superficial stuff…it just becomes the noise, the white noise of our society.”

“Turning to Pollock, Stone said, ‘I don’t want to pick on you, Tom, but you’re ignoring the banks, you’re ignoring television, you’re ignoring the size of this thing, and you’re saying this thing is okay because that’s the way of the world because capitalism will go that way.

“‘The so-called ways of capitalism are not inevitable,’ Stone exclaimed. ‘It’s changed historically. Teddy Roosevelt changed the direction of it. Franklin Roosevelt changed the direction of it. Everybody in Hollywood says, ‘Well, what can I do about it?” These six companies have taken over just like the oil companies, and it’s wrong, wrong, wrong because they’re subverting political will.'”

Ales & Stouts

Obsession

The last truly exceptional hunt-for-a-serial-killer movie was David Fincher’s Se7en. And the next one, I’m fairly convinced, is going to be Fincher’s Zodiac (Paramount, 11.10).

I’m basing this on a recent read of James Vanderbilt’s script, which runs 150-plus pages. This persuades me that what I heard last week is true: Zodiac is going to be a three-hour movie, or close to it.

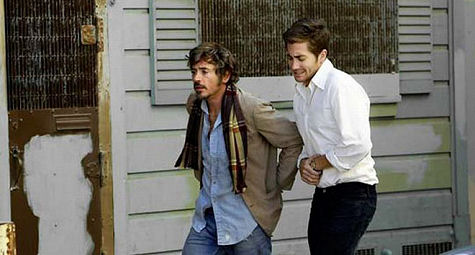

Jake Gyllenhaal, Mark Ruffalo in David Fincher’s Zodiac (Paramount, 11.10)

Scripts never really tell you that much, but reading Zodiac planted an idea that Fincher is again pushing the thriller boundary. Not just in the tradition of Se7en but also Alan Parker’s Angel Heart, another chasing-a-monster film that ended with something pretty startling.

Zodiac is based on two best-sellers by Robert Graysmith, “Zodiac” and “Zodiac Unmasked: The Identity of America’s Most Elusive Serial Killer Revealed“, which are first-hand accounts about the hunt for the Zodiac killer who terrified the San Francisco area in 1968 and ’69.

The chief Zodiac hunters in Fincher’s film (as they were in actual life) are Gray- smith, a San Francisco Chronicle cartoonist at the time (Jake Gyllenhaal), and a blunt-spoken, never-say-die San Francisco detective named Dave Toschi (Mark Ruffalo).

Toschi is understood to have been the real-life model that Steve McQueen based his tough-nut San Francisco detective on in the 1968 Peter Yates film Bullitt.

And of course, the Zodiac killer was the model for Andy Robinson’s psycho killer in Dirty Harry , the 1971 Don Siegel-Clint Eastwood classic…right down to the Zodiac claim about wanting to kill a busload of school children.

Zodiac is partly about the thrill and fascination of the hunt (the scores of hints and clues that pile up are more and more fascinating as the story moves along), and partly about how the complex, seemingly never-ending nature of the case makes Graysmith and Toschi start to go a bit nuts.

Is there such a thing as being too determined to stop evil? At what point do you ease up and say, “I’ve done all I can.” Is it always essential to finish what you’ve started? Should never-say-die always be the motto, even at great personal cost?

Zodiac isn’t just about sleuthing. Deep down I think it’s a metaphor piece about obsessions wherever you find them, and how the never-quit theme applies to heavily-driven creative types (novelists, painters, architects, musicians) as much as cops or cartoonists or stamp collectors or baseball-card traders.

Zodiac and Se7en have at least a couple of things in common: both are heavily focused on the bottled-up emotions and personal frustrations of their two main protagonists, and both films end on a note in which the “crime doesn’t pay” motto doesn’t exactly ring out from the belltower.

Zodiac director David Fincher during filming; laughing Gyllenhaal in b.g.

Let’s just say it: these are two catch-the-bad-guy movies in which the good guys try like hell, but they can’t quite manage to be McQueen or Eastwood in the end.

Partly because the up-and-down life of a cop generally isn’t that heroic or simple. And because Fincher would probably have trouble staying awake if somebody forced him to direct a Bullitt or a Dirty Harry.

Fincher and screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker ended Se7en with a mind-blowing twist in which the killer won and the good guys lost, and in such a way that the final fate of the killer didn’t matter as much as the fact that his vision (which had a certain moral foundation) ended up being fulfilled.

The more I think about Se7en, the more certain I am that it was and is a truly brilliant cop thriller. Not just in the way the story was put together and paid off, but because it echoed a certain clouds-are-forming, it’s-all-starting-to-rot-from-within attitude…a kind of geiger-counter reading of the despair in the air in 1994 and ’95, when Se7en was made and released.

I attended a Writers Guild event last night that celebrated the 101 Greatest Screenplays ever written, and bless their hearts but the WGA voters were blind as bats for not including Se7en.

I’m not going to spill the Zodiac finale in any detail, but anyone who’s read even a little bit about the the hunt for the Zodiac killer knows the culprit was never charged or convicted, although his more ardent pursuers were convinced that he was a pudgy alcoholic and an ex-school teacher named Arthur Leigh Allen, who died in 1992.

The script uses a substitute name instead of Allen’s. It wouldn’t be that big of a deal to mention it, but I’m trying to go lightly here.

Graysmith is the best part Gyllenhaal has ever had, and I’m including Jack Twist in this equation. If he does it right he’ll generate a lot of heat for himself, and I can’t see how he wouldn’t.

Graysmith is a very strongly written guy with a lot of struggle and frustration inside, and the pressure on him just builds and builds. The coup de grace comes at the end when Graysmith delivers a spellbinding 12-page oratory that ties up all the loose ends. (I was reminded of Simon Oakland’s this-is-what-actually-happened speech at the end of Psycho.)

Downey, Gyllenhaal

Robert Downey, Jr. has several good scenes as a Chronicle reporter named Avery. It seems at first as if he’ll be a prominent costar along with Gyllenhaal and Ruffalo, but nope. Anthony Edwards, as Toschi’s partner, has a smaller role than Downey.

Dermot Mulroney, Chloe Sevigny, Ione Skye, Donal Logue and Brian Cox have supporting roles. The IMDB says Cox plays famed San Francisco attorney Melvin Belli, but my script doesn’t even have Belli in it.