The star of Matteo Garrone‘s Reality is a guy named Aniello Arena, who had no acting credits until this came along. The stand-out is that Arena is serving a 20-year jail term for homicide. He was allowed out of the clink to perform in Garrone’s film, but then had to return so he wasn’t at this morning’s press conference. Arena’s sentence began in 1993 so he’s out next year, or so I’ve read.

The second I read this I wondered if Arena’s real-life story might make a more interesting film than Reality. Because Reality is a one-idea movie, and one that we’ve all observed and considered and digested for years, which is that “easy fame and instant celebrity through reality TV shows” is the opiate of the 21st Century masses.

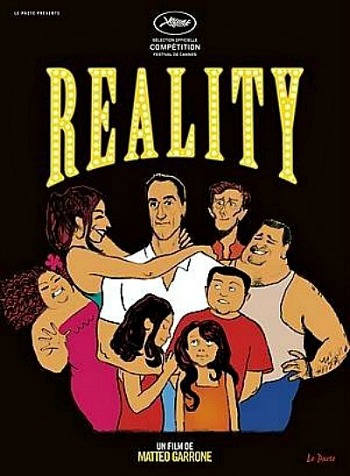

Arena plays a relatively happy Napoli fishmonger and animated family man who does a little party-performing on the side. The story is about his taking part in Grande Fratello, the Italian version of Big Brother, and about how he goes nuts when he isn’t chosen but desperately wants to be, blah blah.

My first tweet said that Reality “is about dreams of reality-TV celebrityhood and enslavement that have engulfed the middle classes.” It has a dream-like visual quality, at times almost Fellini-esque, with buckets and buckets of color and pageantry and flamboyance and gabby-gabby-gabby-gabby. And it’s nothing at all like Garrone’s Gomorrah, not even a distant cousin.

Garrone has described Reality as “a simple, working-class tale” and more or less a comedy. Not by my yardstick. It’s an emotionally warm film in many respects but in a sense it’s almost a cousin of George Orwell‘s 1984 as the focus, once Arena’s delusion kicks in, is about a huge malevolent force taking over people’s lives, and a guy losing himself in a putrid dream.

I also tweeted that it reminded me in some ways of Martin Scorsese‘s The King of Comedy as it dips into a similar celebrity-dream lunacy space, a similar form of blindness. But it’s nowhere near as tough or gnarly as the Scorsese.

The bottom line is that the theme of being engulfed by Big Brother fantasies and thereby relinquishing one’s hold on day-to-day reality didn’t feel all that profound. It felt meh. Somewhere around the 75 or 80-minute mark a sinking feeling began to kick in. And up to that point the film revels in itself — light, color, gaiety, production design — but doesn’t really go anywhere either. I was asking myself at the 10, 20, 30, 40 and 50-minute marks, “Okay, but what’s this movie really about?”

Someone tweeted that at least Reality is delivered in bold strokes, and that it “feels like something Buñuel would make if he were alive.” I disagree — Bunuel never went in for the gobs of digression and color-for-color’s-sake that Garrone does here.