Reconsidering Lives

I spoke early Wednesday evening with Florian Henckel- Donnersmarck, the 33 year-old director of the gripping, pulverizing German-language thriller The Lives of Others (Sony Pictures Classics), which is all but a dead lock for a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar nomination.

Florian Henckel-Donnersmarck at the Beverly Wilshire hotel — Wednesday, 11.8.06, 6:05 pm.

A huge favorite at the Telluride Film festival and the biggest hit of the Toronto Film festival after Borat, The Lives of Others won’t open in a conventional commercial sense until 2.9.07. L.A. audiences will get an early peek in December, however, when it opens here for a one-week qualifying run. The idea is to qualify it for nom- inations in other categories, as Pedro Almodovar‘s Talk to Her and Roberto Begnini‘s Life is Beautiful managed a few years ago.

The Lives of Others is one of the most penetrating German-made “heart” films I’ve ever seen — the love story is tender and impassioned and ripely erotic — but it’s also a riveting drama about political terror.

< ?php include ('/home/hollyw9/public_html/wired'); ?>

I always tell people Lives has four selling points: (a) it’s a first-rate political thriller and a well-sculptured drama, (b) the story isn’t predictable, and it delivers strong arresting emotion at pretty much every turn, (c) it’s sexy as all get out (largely due to costar Martina Gedek, best known on these shores for her Mostly Martha role) and (d) it runs 2 hours and 17 minutes with credits, and yet it feels like maybe 100, 110 minutes at the most.

It’s a gray and dispiriting film now and then, but with a touching “up” element at the finale. It’s a political thriller with real compassion — a movie about spying and paranoia and the worst aspects of Socialist bloc rigidity and bureacratic thuggery, and yet one that delivers a metaphor that says even the worst of us can move towards openness and a lessening of hate and suspicion. Ugliness needn’t rule.

Sebastian Koch, Martina Gedek

It’s about the turning of a bad guy — a Stasi secret policeman (Ulrich Muhe) who’s first seen as a bloodless and fiendish bureaucrat, but whose determination to spy upon and mangle the lives of a playwright (Sebastian Koch) and his actress wife (Gedek) for the sake of career advancement gradually weakens and erodes, and then flips over into something else entirely.

“It’s so easy to make a cynical film,” Henckel-Donnersmarck said early in our chat. “To write or play an unlikable part is easier still. But to write or play someone postive…a positive character…is much harder. Any kind of film with a message of hope, to convey that emotion…to deliver that is a real challenge.

“A film that empowers you is very important to me. Even if it’s painting a positive image just be painting a shadow. if ‘what’s next’ question dies in a viewer’s head …that makes a film drag. People always have to be asking “what’s next?”..you have to keep people awake in that respect, and that means you always have to keep surprising them.”

Set in Berlin, the story mostly takes place in 1984 and ’85, although it jumps to ’89 (the year the Berlin Wall came down) and then to ’91 and ’93. During the 50-year history of the German Democratic Republic (’49 to ’89), the thugs who held the reins of power kept the citizenry in line through a network of secret police called the “Stasi”, an army of 200,000 bureaucrats and informers whose goal was “to know everything.”

Captain Gerd Wiesler (Muhe) is a highly placed Stasi officer who is prodded by a superior, Lieutenant Colonel Anton Grubitz (Ulrich Tukur), to dig up anything negative he can on a famous playwright named Georg Dreyman (Koch) and his actress wife, Christa-Maria Sieland (Gedeck).

At first the suspicions are baseless — Freyman is a dedicated socialist who believes in the GDR. But his loyalties evolve when he discovers that his wife has been pressured into a sexual relationship with a government bigwig, and especially after a theatrical director pal commits suicide due to despondency over his being blacklisted and prevented from working. Eventually Wiesler, who has had their apartment thoroughly bugged, has evidence that Wiesler is working to undermine the state.

And yet his immersion in the lives of this playwright and his actress wife leads, ironically, to a gradual bonding process — a feeling of identification and sympathy for the couple as human beings, artists…people he’d like to know and perhaps share passions with, despite his constricted personality and shadowy Stasi ways. He knows he’s not in their league and probably not worthy of their friendship, but he feels what he feels regardless.

Others won 7 Lola Awards (Germany’s equivalent of the Oscar) — for Best Film, Best Director, Best Screenplay, Best Actor (Muhe), Best Supporting Actor (Ulrich Tukur) and Best Production Design.

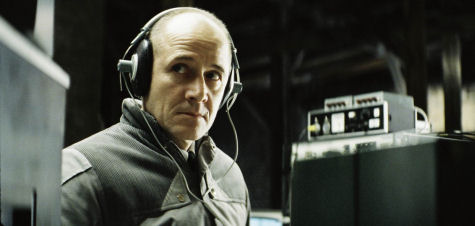

Ulrich Muhe in The Lives of Others

Here’s the shorter first portion of our conversation and the longer second portion. It includes questions and comments from producer and longtime friend Victoria Wisdom, who’d met Henckel-Donnersmarck the night before.

Florian is definitely the tallest first-rate director I’ve ever spoken to — he’s 6’9″. He said he’s looking to direct a U.S.-funded film next, although he’s a ways from deciding what that will be. He’ll be in Los Angeles for the next few days. He said something about returning for the one-week December opening and then again in January to promote the early February opening.